Big L.A. institutions refused to host a mayoral debate. Are disruptive protests to blame?

- Share via

When high-level USC officials pulled out of hosting a mayoral debate last month, they cited “the escalating tension in modern politics.”

A triggering event, they said, was a Los Angeles City Council meeting days earlier where a citizen angrily confronted the council president and chaos erupted.

After some scrambling, organizers salvaged the debate between Rep. Karen Bass and businessman Rick Caruso. It was moved to the Skirball Cultural Center and is scheduled for Sept. 21.

But USC’s decision shows how precarious a fundamental part of politics has become in Los Angeles, as protesters unhappy with the state of the city have made some would-be debate organizers leery of wading into the fray.

Another school, Cal State Northridge, recently said it wasn’t in a position to hold a mayoral debate either, citing staff shortages.

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

With only two debates nailed down as the mayoral race heads into its frantic final months, voters may have few chances to see the candidates go head to head before deciding who should run the nation’s second-largest city.

Other factors are also making scheduling a debate difficult — sporting events like “Monday Night Football” and the MLB playoffs, as well as Jewish holidays and the perennial challenge of getting the candidates in the same room at the same time.

Those debates that do occur are being held with tight security and strict rules about reserving a spot in the audience. During the primary season, some candidate forums were open to the public and light on security. Protesters interrupted speakers and in some cases shut down events featuring the candidates.

The Aug. 9 City Council meeting that sparked concern among USC administrators was far from the only public meeting in L.A. that has been disrupted by protesters angry about police misconduct and city officials’ homelessness and climate policies. It was the second time in as many weeks that protesters had delayed a vote on an expansion of laws prohibiting homeless encampments.

The ratcheting up of local tensions comes against a national backdrop of political anger that has intensified in recent years.

“These disruptions are more frequent and more intense,” said Fernando Guerra, director of Loyola Marymount University’s Center for the Study of Los Angeles.

A public speaker at the Los Angeles City Council meeting climbed over a bench and moved toward council President Nury Martinez. Officers apprehended a second member of the public on the council floor moments later.

After USC withdrew, Loyola Marymount University and Univision 34 stepped up as sponsors of the Sept. 21 debate along with Fox 11, The Times and KPCC, which had already been partnering with USC.

Guerra said he was happy to have his school join as a sponsor — a decision likely made easier because the debate isn’t taking place at LMU.

During the primary, Guerra hosted a mayoral debate on the LMU campus that was disrupted by more than half a dozen protesters who stood up one after another and screamed criticisms at the candidates.

Guerra was initially frustrated that the candidates’ voices were being drowned out, but he came to see it as a learning experience for his students.

He believes the increase in protests this year shows the anger among some voters who feel that neither of the mayoral candidates reflect their views on issues like homelessness and policing.

“It brought to life a lot of what I was talking about in the class,” he said. “It brought to life different ways of political expression, which some people will disagree with.”

The email, which was sent to partner organizations and obtained by the Times, noted that the Dornsife Center “did not make the cancellation decision” but was “bound by it.”

The USC Dornsife Center for the Political Future, which was organizing the USC general election debate, said in an Aug. 11 email that the decision to pull out was made by “senior administrators.”

The email, which was sent to partner organizations and obtained by The Times, noted that the Dornsife Center “did not make the cancellation decision” but was “bound by it.”

The decision, which was reached after a “formal threat assessment,” was also motivated by “the desire to keep potential disruptions at bay,” with students on campus for the fall semester, the email said.

In addition to escalating political tensions and the recent City Council meeting, the email cited the cost of security and a shortage of personnel. The evening would also have included a debate between sheriff’s candidates Alex Villanueva and Robert Luna. (The debate on Sept. 21 will feature Villanueva and Luna as well.)

The decision, which was reached after a “formal threat assessment,” was also motivated by “the desire to keep potential disruptions at bay” with students on campus for the fall semester, said an email notifying partners of the cancellation.

A USC spokeswoman, who would only be quoted if her name wasn’t used, said in a written statement Friday that the university is “pleased to have hosted a well-attended mayoral debate during the primary, and we’re happy to consider hosting again in the future.”

USC is one of the city’s most important intellectual centers, organizing countless forums for public dialogue. That the school, which has hosted a gubernatorial debate and multiple mayoral debates, felt it couldn’t pull off an event of this nature was a departure from past practice.

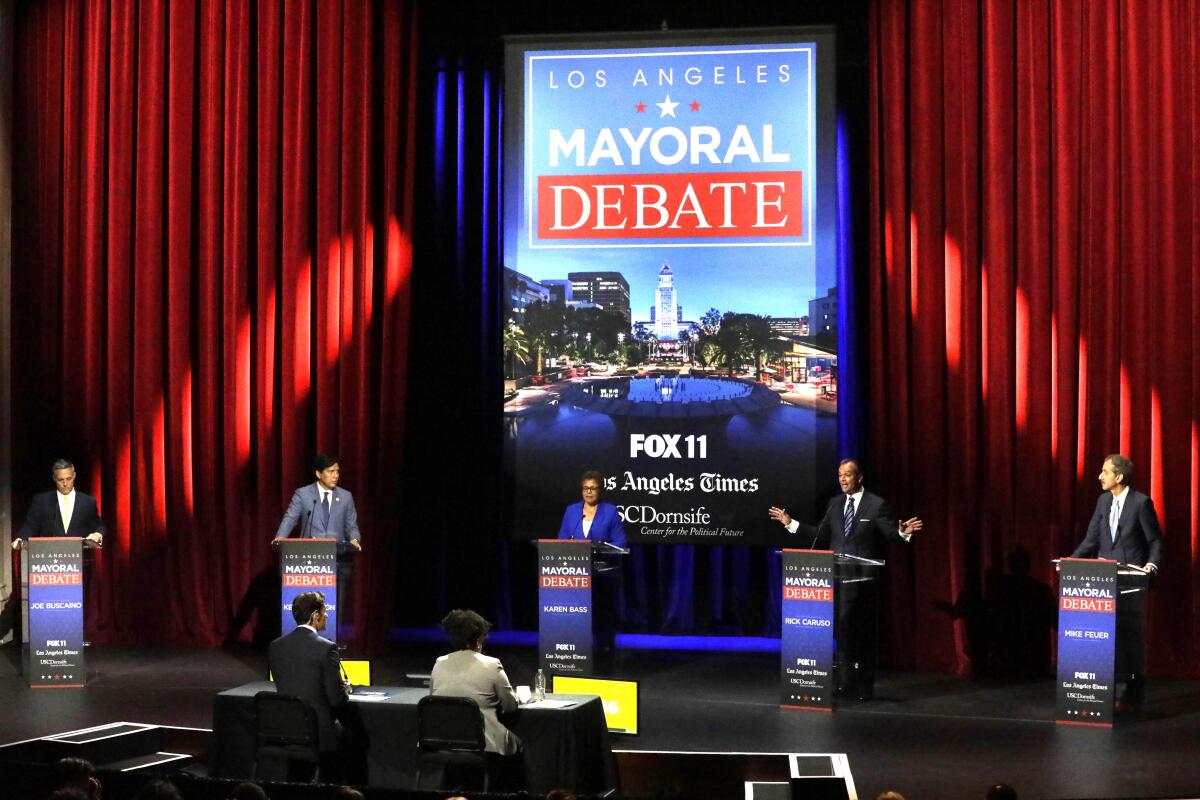

Even during the primary, the USC Dornsife Center, along with The Times and Fox 11, hosted a debate on campus. It included five candidates and was the only one of the season’s three televised debates to conclude without a disruption and people being forcibly removed from the event.

The two mayoral candidates who would have shared the stage at USC have deep ties to the school.

Caruso, a USC graduate, is a member of the board of trustees and formerly served as the board’s chair. His time as the board’s chair tenure has been criticized by some on campus for lacking transparency amid several scandals, including a school gynecologist who was accused of sexually abusing students.

Bass is an alumna of the physician’s assistant program where she later worked. She has been criticized by groups supporting Caruso for taking a $95,000 scholarship from USC to pursue a graduate degree in social work while she was in Congress.

The congresswoman came in first in the June 7 primary, besting Caruso by 7 percentage points. Recent polling by The Times and the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies found that she has widened her advantage over the businessman to 43%-31% among registered voters, with 24% undecided.

The Sept. 21 debate at Skirball, broadcast by Fox 11 and Univision 34 in front of a live audience, will be the first of the general election season followed by a radio debate hosted by KNX on Oct. 6. Univision has been trying to organize its own debate for Sept. 27.

This week, Caruso sent Bass an open letter decrying her apparent unwillingness to show up for that faceoff.

“It is irresponsible that you would pass up the unique opportunity to connect directly with Latino voters,” he wrote.

Sarah Leonard Sheahan, a Bass spokeswoman, said the congresswoman couldn’t make that date work because of a previously scheduled event.

Bass was “happy to participate in dozens of forums and debates during the primary season, all of which Rick missed except two,” Sheahan said.

Mayola Delgado, a spokeswoman for Univision 34, told The Times that “the invitation to participate in the debate still stands” and that the station is waiting for a response from Bass.

At a certain point after USC pulled out, Univision 34 was approached about joining as a partner. Fox 11 anchor Elex Michaelson — who helped organize the Sept. 21 debate and is moderating — said he is excited to have the station on board to reach Spanish-speaking voters.

“Univision will have a moderator at the table and input about the questions that will be asked at the first and likely biggest debate of the campaign season,” Michaelson said.

Several other television stations are hoping to host debates, but their plans have not been finalized.

Stuart Waldman has been trying to set up a Bass-Caruso conversation that would take place in the San Fernando Valley. The Valley accounted for 38% of ballots cast in the primary, and Caruso won there by 7.5 percentage points. Now he’s up by just 2 points, according to The Times’ latest poll.

Waldman, president of the Valley Industry & Commerce Assn., was in talks with Spectrum News and thought the Soraya, a 1,700-seat theater on Cal State Northridge’s campus, would be the perfect venue for a debate.

This week, according to Waldman, the school said it was a no-go.

Nichole Ipach, Cal State Northridge’s vice president for university relations and advancement, said the school doesn’t have enough staff to host “such a large and complex event.”

In an email to The Times, she noted that students will be fully in person this fall for the first time since the pandemic began.

“As a result, our limited staffing resources are keenly focused on supporting our students and important campus events that we have not had the ability to offer since the spring of 2020,” she wrote.

Waldman believes that the disruptions to the spring debates may have played a part in the school’s decision. He is still trying to organize a debate in the Valley.

“It’s sad that you have a handful of people, and their goal is to disrupt and stop people from engaging in debate,” he said. “And they get cheered on by their other disruptors.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.