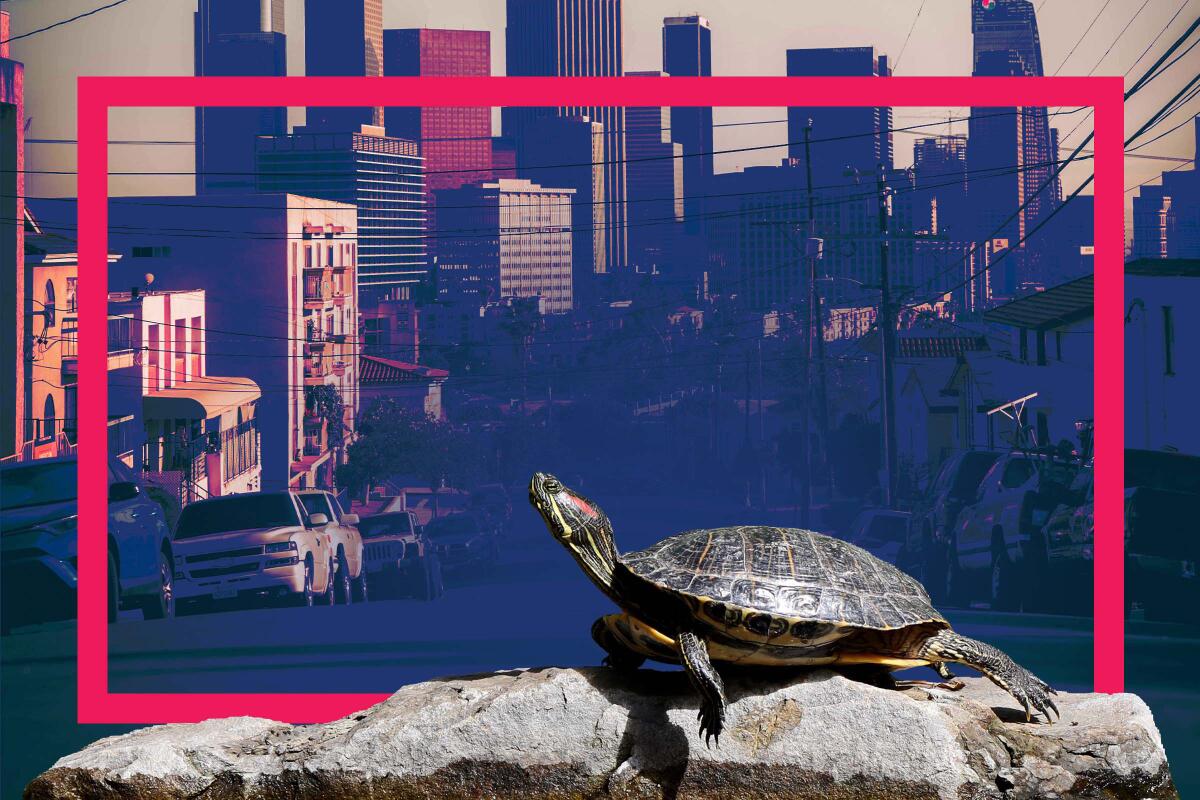

What’s the deal with all the turtles in Los Angeles parks?

- Share via

Last year, we began asking readers to send us their pressing questions about Los Angeles and California.

Every few weeks, we put the questions to a vote, asking readers to decide which question we should answer in story form.

This question, posed by Dee Villalobos, was included in one of our latest reader polls: How do turtles survive in L.A. parks?

Imagine you’re meeting up with friends for a picnic in your favorite L.A. park. You scan the grass for the optimal place to set up a blanket and decide on a shady spot near the pond. As you chat and enjoy your lunch, you notice a few turtles basking on a sun-dappled log and smile. It’s one of the beauties of life in Los Angeles — that in the midst of a sprawling metropolis, wildlife coexists alongside humans.

One problem, though: By and large, the turtles you see in city parks across Los Angeles aren’t native to California.

Instead, many are native to lands hundreds of miles away, in the Mississippi Valley, from Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico (though their natural range can reach as far west as eastern New Mexico, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife).

But Southern California does have a native turtle.

Whatever’s puzzling you about life in L.A. and California, we want to hear about it.

Once upon a time, the native southwestern pond turtle “used to be all through the rivers and streams of the greater L.A. basin,” said Brad Shaffer, director of the UCLA La Kretz Center for California Conservation Science and Distinguished Professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

Flashing forward to today, it’s only possible to see the southwestern pond turtle in a few isolated places in L.A. County — and it’s a candidate for listing under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, along with the closely related northwestern pond turtle, Shaffer said.

As the Earth warms and the drought deepens, a network of biologists and conservationists are racing to rescue California’s most threatened species.

“If we don’t take action then they will disappear,” said Rosi Dagit, a senior conservation biologist at the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains, via email. “Our turtles have unique genetic characteristics that preserve biodiversity of the species.”

Zooming out, if L.A. County’s native turtles are imperiled, then the future of the southwestern pond turtle species could be jeopardized. Eventually, if too many animal species disappear, Earth’s ecosystems could be thrown out of balance.

So, where did our native turtles go? And how did the non-native turtles get here?

Generally speaking, “the turtles that we see in pretty much every urban park pond are turtles that were once somebody’s pet and then were abandoned. Or they’re the offspring of formerly abandoned pets,” said Greg Pauly, curator of Herpetology and director of the Urban Nature Research Center at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “That covers about 99.9% of the turtles in urban park ponds in this area.”

“The turtles that do well are a few species of non-native turtles, and the main one is the red-eared slider,” said Shaffer.

Red-eared sliders are “beautiful, especially when they’re babies.” But they don’t stay little forever, with some adult turtles reaching nearly one foot in length — leading many people to “re-home” their grown-up turtles by dumping them in urban ponds and lakes.

It’s illegal to release turtles — or any aquatic plant or animal — into California waterways. But the damage has been done — in California and far beyond.

“They’re in Europe, they’re all over United States, they’re in South America, they’re in Australia [and beyond],” Shaffer said. “They breed on their own now, in many parts of the world, including in Southern California.”

How did a reptile native to the Mississippi Valley spread so widely across California?

Pandemic or not, Griffith Park takes you to L.A.’s urban edge and plunges you into what remains of our wilder side. Let this mini-guide send you on your way.

“One of their keys to success is they’re a real generalist species,” Shaffer said. “They’ll eat almost anything” and are capable of nesting in “a whole variety of different places” — including parks and other public spaces in Los Angeles. If a sprinkler turns on and gets the eggs wet, the egg can survive — unlike the eggs of native pond turtles in Southern California.

“They’re just kind of built to be around people,” Shaffer said.

But despite their adaptability and strong population numbers, life is far from perfect for red-eared sliders that live in L.A.’s urban ponds and lakes.

“There’s a lot of competition for food, there’s competition for places to bask,” Pauly said. “You’ll see scars on some of the females who are just being perpetually harassed by the males.”

“A lot of [turtles in L.A. ponds and lakes] are sick, a lot of them have fish hooks in them,” added Robert Fisher, a supervisory research biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Western Ecological Research Center.

In addition, red sliders who were born and raised in captivity for part of their lives now have skeletal issues and shell deformities because of “inappropriate care,” Pauly said.

“It’s hard for me to see an urban park pond full of turtles and not be a little depressed,” he added.

L.A. Times readers are curious about weather, wildfire and relics of the Cold War, among other things.

The threats facing red-eared sliders — which include getting hit by a car or attacked by a dog or raccoon — would be similarly faced by the native southwestern pond turtle, if it ever made a resurgence in Los Angeles (in fact, cars, dogs and raccoons already pose a threat to southwest pond turtles in urban wildland areas).

Southwestern pond turtles are also forced to compete with red-eared sliders for food, Pauly added.

Drought, floods, and wildfires threaten the future of the southwestern pond turtle. “Among the top five threats to [southwestern pond turtles], most impacts are associated with, and potentially driven by, climate change,” concluded a paper published last year in the Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management.

The numbers paint a bleak picture.

In 1986, the Southwestern Herpetologists Society documented the presence of western pond turtles in 30 locations throughout the Santa Monica Mountains, said Dagit. “In 2009, out of those 30 sites, we found turtles in eight.”

If Angelenos want native turtles to thrive, things will need to change, experts say.

Southwestern pond turtles need water to survive. “They don’t eat when they’re on land. And they don’t reproduce and mate when they’re on the land,” Dagit said. “As a result of the drought in the past 10 years, our turtle populations have been really hammered.”

Diamond Valley Lake, an “inland ocean,” is Southern California’s prime defense against drought.

Last September, Dagit had the idea to “run hoses 2,000 linear feet, up an elevation of over 200 feet to get water to some remote refugio pools that we know support the turtles, because they hold the water the longest.”

“We figured if we could support keeping water in those two pools, we give the turtles a little bit of extra opportunity to feed as well as to mate, even when everything else dries down,” she explained. “I had 25 volunteers help carry 2,000 feet of hose up a very steep rocky ravine to do a proof of concept. And it worked.”

In May, “we installed a more reliable system,” Dagit said, “and have been able to keep water levels in the pools sufficiently high to support summer feeding and mating.”

Water is a tricky thing for Southern California’s native turtles. On one hand, it’s necessary — and on the other, man-made pond, lakes and reservoirs have enabled non-native species to thrive.

“Historically, year-round ponds and lakes were uncommon in California because of our long, dry summers. Native pond turtles evolved in this climate and can handle that long dry period,” explained Pauly via email. “With the permanent water, people [and often government agencies] introduced non-native fish like bass and sunfish as well as non-native bullfrogs. The fish and bullfrogs then eat our native hatchling turtles. Red-eared sliders then were also able to get established as they also require permanent water.”

Pauly’s suggested fix: “If we manage water resources such that they dry down occasionally, we can exclude many of these non-native predatory species and thereby help out our native pond turtles, native frogs, and many other species as well.”

From Will Rogers State Beach to Tule Elk State Natural Reserve, these state parks are all less than three hours from Los Angeles.

This strategy can be quite effective, especially if you capture any native turtles and hold them appropriately while removing the invasive species, Dagit added.

Southwestern pond turtles also respond well to vegetation around bodies of water. Allowing plants to grow around lakes and ponds as seen in the Ballona Wetlands, would be beneficial, Shaffer suggested. Park fencing, to keep turtles from wandering into roads and away from dogs who might bite the reptiles, would also help.

These steps “may be hard to accomplish,” Shaffer said, “ but they’re doable if there’s a will.”

Californians can help turtles in a variety of ways. If you’re hiking and see one on a trail, let it be — some well-meaning hikers assume turtles are lost and take them from their habitat to a wildlife center, Fisher said.

Driving safely while in turtle habitats is also important, he continued.

When complete, the 200-foot-long, 165-foot-wide bridge over the 101 Freeway in Agoura Hills will be the largest of its kind in the world.

And, if you buy a turtle from a pet store and decide you can’t keep it, don’t release it into a pond, lake or other waterway, Fisher said. “Take it back to the pet store where you got it from.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.