Biggest polio threat in years sparks alarms from New York to California

- Share via

Delays in getting children vaccinated during the COVID-19 pandemic and antivaccination sentiment in general may be fueling the most serious threat of polio in the U.S. in years, raising alarms from New York to California.

In the last few weeks, health officials in New York identified the first person in nearly a decade in the U.S. to be diagnosed with polio. The person suffered paralysis. Since then, the polio virus has been found in wastewater not only in two counties in the area where the patient lives but also, as of Friday, in New York City.

The virus may be rebounding worldwide. The Jerusalem area this year suffered an outbreak, and the virus showed up in London wastewater in June.

Now, health experts and officials in California are voicing concern.

Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said there’s discussion about tracking polio in wastewater, especially in areas with low vaccination rates. This makes sense, experts said, given the high numbers of travelers between Los Angeles and New York and because people can be contagious with polio while having no symptoms.

“The detection of poliovirus in wastewater samples in New York City is alarming,” Dr. Mary T. Bassett, the New York State Health Commissioner, said in a statement. “For every one case of paralytic polio identified, hundreds more may be undetected.”

Health officials in New York are “treating the single case of polio as just the tip of the iceberg of much greater potential spread. As we learn more, what we do know is clear: The danger of polio is present in New York today,” Bassett said.

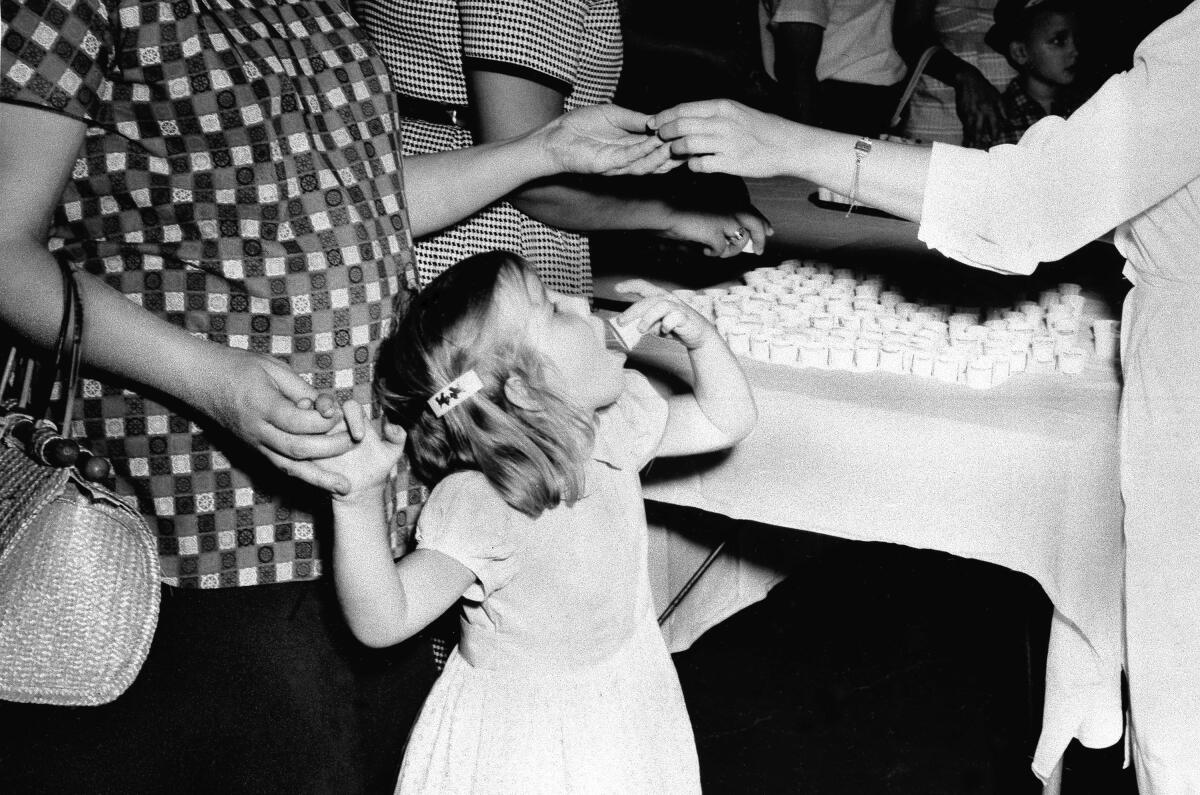

There is no cure for paralysis caused by polio, said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a UC San Francisco infectious-diseases expert. But polio can be prevented by immunization, which is more than 90% effective. Babies should be given three doses; a fourth is given to children between 4 and 6.

About 75% of people who get infected with polio have no symptoms; the others can have flu-like symptoms. It can take three to six days after exposure to the polio virus for nonparalytic symptoms to appear. Paralysis can occur seven to 21 days after infection.

Patients generally get infected through the mouth, typically by hands contaminated with an infected person’s fecal matter, but the virus can also spread through an infected person’s sneeze or cough.

Paralysis or weakness in the arms or legs can occur in 1 out of every 1,000 people infected with polio, Chin-Hong said. The disease can cause paralysis because the virus can infect the spinal cord.

Between 2 and 10 of every 100 infected people who have polio-induced paralysis die, because the virus can harm the muscles that help them breathe.

“Even children who seem to fully recover can develop new muscle pain, weakness or paralysis as adults, 15 to 40 years later,” the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says. This is known as post-polio syndrome.

Chin-Hong said the emergence of polio in New York is concerning enough for clinicians to familiarize themselves with the disease.

“We’re worried, because this is the first case in the U.S. identified in almost 10 years,” Chin-Hong said at a recent town hall.

The case of paralytic polio occurred in Rockland County, a suburban area just north of New York City. Rockland County is notable for having a significant population of Orthodox Jews, among whom there are low immunization rates.

Hundreds of thousands of Israel’s ultra-Orthodox Jews have yet to receive their COVID-19 shots, despite the ravages of the disease on their community.

Outbreaks of infectious diseases have hit Rockland County before. In late 2018, the county was the epicenter of a significant measles outbreak in Orthodox Jewish communities after being first detected in an unvaccinated teenager. The seven-month outbreak was the longest in the U.S. since 2000, according to a CDC report.

Additionally, large outbreaks of COVID-19 have been observed in Orthodox Jewish communities in Rockland County and in Brooklyn, linked to low rates of vaccination.

The polio patient is a 20-year-old unvaccinated man who traveled to Hungary and Poland earlier this year and was hospitalized in June, the Washington Post reported, citing a public health official who spoke on condition of anonymity. The New York Times reported that the patient is a member of the Orthodox Jewish community.

Genetic analysis of a polio virus sample from the patient indicates that it was picked up from a person who had received the oral polio vaccine, which has not been used in the U.S. since 2000, health officials said.

The oral vaccine contains a weakened live polio virus. “If allowed to circulate in under- or unimmunized populations for long enough … the virus can revert to a form that can cause illness and paralysis in other people,” the CDC says.

Oral polio vaccine is used in parts of the world because it’s easy to administer, given in the form of drops.

Since 2000, the U.S. has used only the inactivated polio virus vaccine, which cannot cause disease.

Following the public disclosure of the polio case, officials in New York began testing wastewater for signs of virus in stool samples. This month, officials confirmed the presence of polio virus from wastewater samples collected in June and July in Rockland County and neighboring Orange County; they said this was evidence of local polio transmission.

The wastewater samples detected in both counties were found to be genetically linked to the index polio case.

“If you’re an unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated adult, please choose now to get the vaccine,” Dr. Ashwin Vasan, commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said in a statement. “Polio is entirely preventable, and its reappearance should be a call to action for all of us.”

The case in New York is genetically linked to polio samples identified in Israel and Britain, health officials said.

The outbreak in the Jerusalem area began after an unvaccinated 3-year-old developed paralysis in February and was later publicly disclosed as having polio, according to the World Health Organization. Israel’s last prior polio case occurred in 1988.

Eight additional children have since tested positive for polio, all asymptomatically. Of the nine children in the outbreak, eight were not fully vaccinated for their age group, according to Israel’s Ministry of Health.

According to the Jerusalem Post, Israeli health officials responded to the outbreak — which occurred in Orthodox Jewish areas — with a campaign to encourage parents to get their children caught up with vaccinations. By early July, the outbreak was deemed to be under control, with no polio virus found in sewage in the prior month.

In New York, Rockland and Orange counties have some of the lowest rates of childhood polio vaccination, with only about 60% of 2-year-olds having received three doses. The statewide polio vaccination rate among 2-year-olds is about 79%.

In New York City, about 86% of children between 6 months and 5 years have received three doses. Vaccination rates are around 60% in some neighborhoods of Brooklyn, such as Williamsburg and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

About 80% of a population needs to be vaccinated against polio to keep the virus from spreading, Chin-Hong said.

Spread of polio may end up becoming “a phenomenon that we’re seeing as vaccination rates go down in communities,” Chin-Hong said.

“I’m really worried because, as we saw in 2015, there were poor vaccination rates in many communities,” he added, referring to the 2014–15 measles outbreak that began at Disneyland and spread across eight states, Canada and Mexico, transmitted mostly by unvaccinated people. “We know that the COVID-19 pandemic fueled the largest continued backslide in vaccinations in three decades.”

A study published in October in the journal JAMA Pediatrics found that weekly pediatric vaccination rates in eight U.S. health systems were substantially lower during an early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Interventions are needed to promote catch-up vaccination,” the report said.

In response to the 2014–15 measles outbreak, California passed legislation barring vaccine exemptions, including for polio, among schoolchildren based on a parent’s beliefs. Medical exemptions are allowed.

Assessing California’s polio vaccination rate is tricky, particularly among adults. But data available for school-age children indicate that the state’s coverage is robust.

For the 2019–20 school year, 96.5% of incoming kindergarteners were fully vaccinated against polio, state figures show. That’s up from 92.6% in the 2013–14 school year.

Data for more recent years are not available. The state Department of Public Health notes that “routine vaccination rates in California, including for polio vaccine, decreased during the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“As the new school year approaches, more than 1 in 8 children in California need to catch up on routine vaccines that were missed or delayed during the pandemic,” department officials wrote in a statement to The Times. “Longstanding school immunization requirements and other measures have assisted with catch up of needed immunizations.”

As is always the case with a state as large and diverse as California, overall coverage tells only part of the story. In the 2019–20 school year, fewer than 93% of incoming kindergartners in 10 counties — El Dorado, Glenn, Humboldt, Kern, Mendocino, Mono, Nevada, Santa Cruz, Sutter and Trinity — were vaccinated against polio, state data show.

In Los Angeles, polio vaccine coverage among kindergarteners has been around 97% “and hasn’t markedly changed over time,” according to the county Department of Public Health. However, data from the COVID-19 years are not readily accessible.

Ferrer said efforts are underway in L.A. County to work with pediatricians “to make sure that we’re getting children back in for their routine vaccinations.”

“We’re talking about polio today, but ... because of the falloff in complete vaccinations for children during the pandemic, this could be any of a number of infectious diseases that in the past we really didn’t worry that much about,” the public health director said. “So the big push right now is for us to make sure, again, that families have good information, they have good access.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.