The Dodgers lost their voice when Vin Scully died. Angelenos lost a family member

- Share via

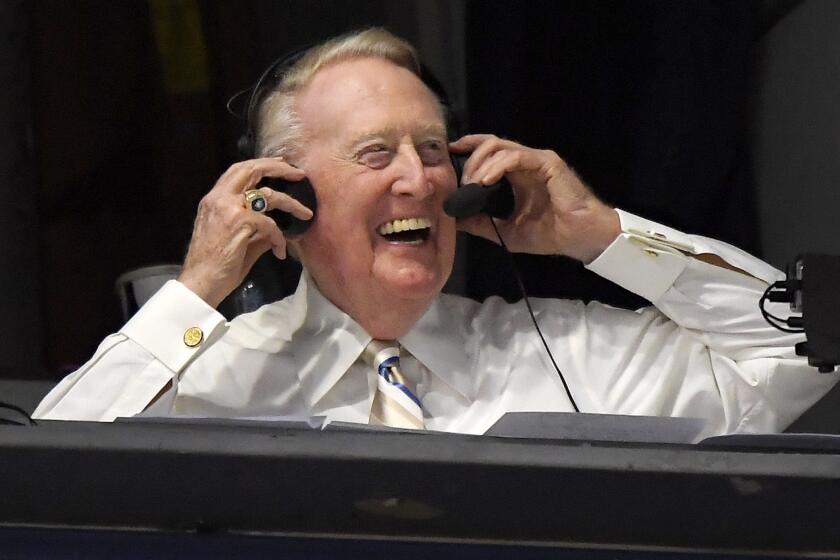

For legions of Dodgers fans, Vin Scully was the voice of their beloved baseball team. But for many Angelenos, the ginger-haired broadcaster was more like a family member. A grandfather, a tío — someone whom they welcomed into their homes on game day.

As heartbroken fans mourned Scully’s passing at age 94, it felt, they said Wednesday, like a death in the family.

“It almost felt like I lost my father again,” said Desiree Jackson, who took the bus from skid row to Dodger Stadium to lay flowers and pray at the makeshift memorial that sprang up there overnight. “I fell in love with sports because of my dad, and my brother, and Vin.”

The 44-year-old wore a World Series hat and a long blue dress in honor of the legendary announcer, who died Tuesday at his home in Hidden Hills. Jackson grew up listening to Scully on the radio, and his voice, she said, is inextricable from memories of her late father.

Vin Scully, voice of the Dodgers for more than six decades, died Tuesday

The memorial at the stadium entrance brought an outpouring of offerings and tears. Fans who came to remember the announcer described a figure who transcended divisions and transported fans to the game — from wherever they were listening.

“Generations of my family, that’s how we became Dodgers fans, listening to the broadcast,” said Tiffany Morales, 21, who joined dozens of mourners outside the stadium. “He was like a grandpa to us.”

Along with prayer candles and bouquets, fans left bags of Dodgers peanuts, a blue and white striped serape and a baseball with “It’s time for Dodger Baseball” — Scully’s trademark opener — inked above the stitching.

Eight-year-old Jax Gutierrez Alvarez, sporting Dodger blue, came bearing flowers. Among the Little League pitcher’s favorite pastimes is re-watching Game 1 of the 1988 World Series — won by the Dodgers on Kirk Gibson’s dramatic ninth-inning home run — with his grandparents.

“I love Vin Scully’s voice,” he said. “My favorite part is when he says ‘a high fly ball into right field, she is gone!’”

A tearful Lupe Guillen of Lincoln Heights brought a single white rose, a Dodgers flag and a handful of Mardi Gras beads to add to the memorial.

“I’m brokenhearted,” she said. “My uncles used to live in Chavez Ravine. They got deported, but they would listen to him on the radio in Tijuana. He brought you right to the spot.”

Alain Gomez, 38, looked on with tears in his eyes as he recalled the summers spent listening to Scully on the radio with his brothers. A lifelong Dodgers fan, a guy who bleeds Dodger blue, he wore a new Vin Scully T-shirt and bore a sleeve of Dodgers tattoos.

“It was what I grew up with,” Gomez said. “The stories he would tell about every player, you knew he loved the game.”

In East L.A., Carlos Ayon parked in front of a Scully mural painted outside of Paradise Bar. In it, a grinning Scully wore a suit with a Lakers jersey over it. Two candles flickered at the base of the wall.

Ayon is a lifelong resident of East L.A. He took the day off from his office job and planned to snap photos with his Sony a7 II camera at the stadium and here, at Lupe’s Burritos, where a “Vin Scully Av” sign hangs.

Growing up in L.A., he said, meant growing up with the Dodgers and with Scully.

“He became basically a family member,” the 36-year-old said, providing life’s background noise, which Ayon found “comforting.”

Ayon gestured at the mural of Scully and the one next to it, of the late Lakers star Kobe Bryant.

When Bryant joined the NBA, Ayon was about 10. Although many things changed as he grew up, some things, thankfully, never did.

Bryant and Scully “were the constants,” he said. “That’s why it hits people so hard. Both of their deaths.”

Yet another memorial sprung up Wednesday at Scully’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Jesús Carcamo, 25, left his lucky Dodgers hat there at the base of a wreath of blue roses, white hydrangea and palm-sized white orchids placed by the Hollywood Historic Trust.

“I wanted to leave one of my favorite hats, the one I used to wear whenever I went to Dodger Stadium,” he said.

Fred Thomas III, who wore a black Vin Scully T-shirt and a crisp Dodgers hat, had also come to Scully’s star to pay his respects. A lifelong Dodgers fan, he recalled listening to Scully call the game from his grandmother’s living room in the 1950s.

“Everyone had a radio, and you wanted to listen to Scully,” he said. “He was a storyteller you could trust.”

Thomas said he admired how Scully kept listeners apprised of what was happening on the field, even as he wove his famous yarns.

“Scully would keep you in the game,” he said.

Behind the register at Toro Grillhouse in Glendale, owner RJ Liquigan wore a Justin Turner jersey (he’s the Dodgers’ third baseman, for the uninitiated), a Dodgers cap and a replica World Series ring as a way to pay his respects to Scully. As he rang up orders, Spectrum SportsNet commemorated the broadcaster on a nearby TV.

Throughout the day, people had dropped by to take photos of the about 25-foot-tall mural of Scully in Liquigan’s parking lot. Painted by L.A. muralist Alex “Ali” Gonzalez in 2018, it shows Scully in a suit, microphone in hand. On Wednesday afternoon, white and red roses had been left at its base.

To Liquigan, it’s Scully “who represents the Dodgers the most.”

“He’s a legend,” he said. “There’s no one like him.”

Liquigan became a fan of the Dodgers in 1988, when they won the World Series. Five-years-old at the time, he watched the game in the nursing home where his mom worked.

He recalled Gibson’s home run in Game 1 and Scully’s memorable words: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened.”

“I hope that we can win the 2022 World Championship for Vin,” Liquigan said. “Win for Vin.”

Richard Choi also remembered that famous game in 1988.

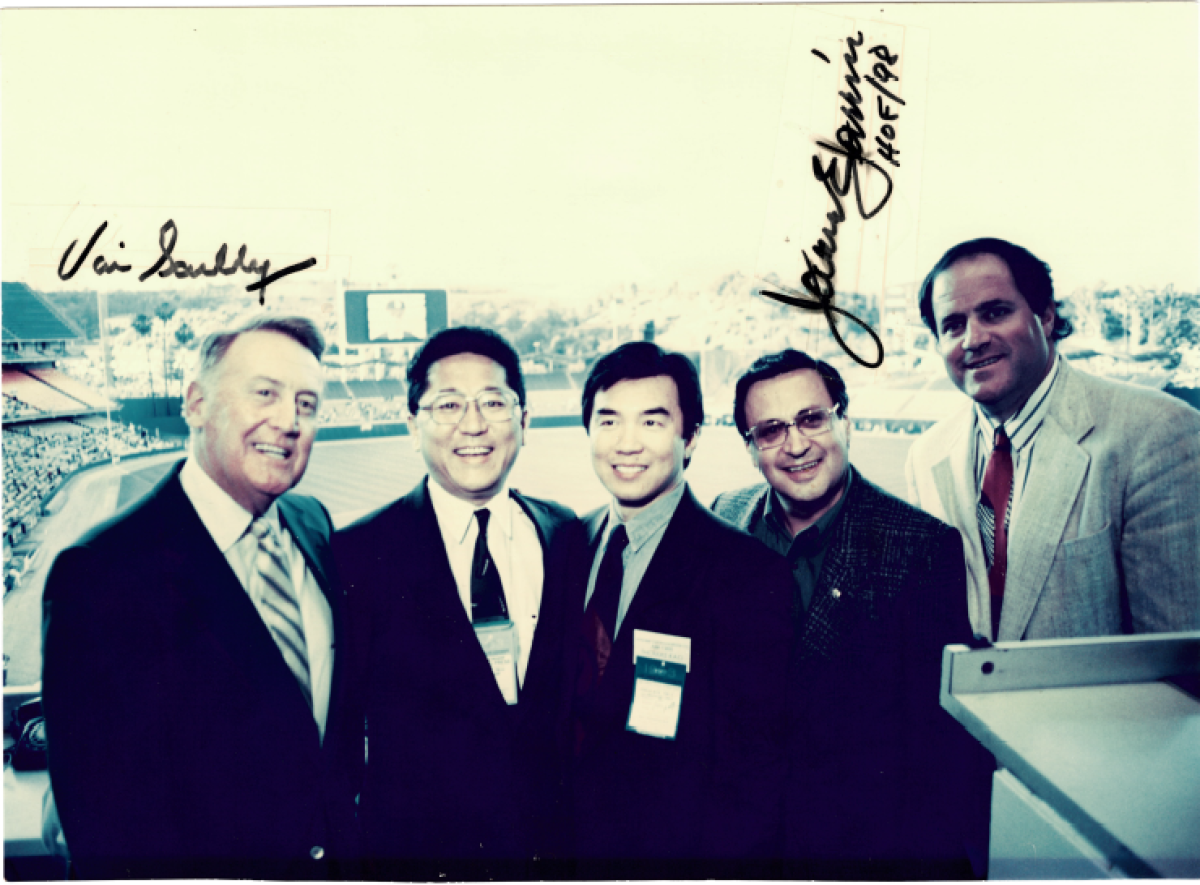

For years, three hours before every Dodgers home game, Choi would arrive at the ballpark and look for Scully.

Choi would show Scully the line-up cards for the game and ask the famous broadcaster how to pronounce “Abreu,” the last name of one of the players. Scully would read the players’ names out loud for Choi, a Korean American broadcaster who served as commentator on Dodgers games for Radio Korea from 1990 to 2021.

“He’s like a father figure to me,” Choi said Wednesday morning during an interview in the Radio Korea studio. “He was the first one I sought in the Dodger Stadium.”

For the 74-year-old, Scully was a father figure in more ways than one. Scully taught Choi English and the love of baseball after he arrived in Los Angeles in 1974. Scully guided Choi when Radio Korea became the first station to broadcast Major League Baseball games in Korean in 1990.

And through Scully, Choi said from the studio in Koreatown, Southern California’s burgeoning Korean American community began to understand the region’s sports, culture and identity.

“For Korean Americans, he taught the true taste of baseball,” Choi said.

Soon after Choi started calling Dodgers games, he once asked Scully about the famous call Scully made in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series. Why did Scully say “she is gone,” rather than “he is gone” or “it is gone” as the ball left the field, Choi asked Scully.

A man would describe the cars and yachts they love and take pride in as “she,” Choi recalled Scully responding. Describing the ball as “she,” Scully said, added passion to that historic moment.

“When I heard that,” Choi said, “I thought he was a genius.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.