- Share via

My assignment was to illustrate a story on how blue states might receive an influx of abortion patients from neighboring red states after Roe vs. Wade was overturned. That’s why I was in New Mexico last Thursday, when many thought the Supreme Court would issue its ruling.

I had emailed two clinics, including the doctors who worked there. After many email exchanges, the Center for Reproductive Health at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque agreed to let me come. The doctors and staff welcomed me, granting me more access than I had expected.

I arrived at 8 a.m. with Elizabeth Gibson, my escort from the university, waiting for me in the parking lot. I soon met a new family physician and other medical staff.

What unfolded over that day and the next embody the challenges of being a photojournalist in such situations — how to portray reality accurately but compassionately, preserving some privacy for subjects in their most personal and vulnerable moments.

Within a few minutes, I was able to photograph a 25-year-old patient during her ultrasound procedure. Though she didn’t want her face shown, the photos are intimate and tell a story.

At 8:31 a.m. my phone began to vibrate.

I looked down at the caller ID, and it was our Houston bureau chief Molly Hennessy-Fiske on the line.

“I think I can get us into an abortion clinic in San Antonio, Texas, tomorrow,” she said.

In a whispered tone, I said, “We need to go.”

We didn’t know when the Supreme Court would issue its ruling. Nothing was certain. I was thinking to myself how important and historic it would be to be inside a clinic when the decision came down, especially in a red state.

I put my phone into my back pocket and quickly headed back to the staff work area, where I photographed the doctor and her resident viewing an ultrasound of a 39-year-old woman who was seeking an abortion. The woman already had four children.

The woman agreed to let me photograph her procedure without revealing her identity. I entered the exam room, where 1980s music was playing softly through ceiling speakers. The room was dark except for the small and bright exam room light.

I wanted to capture the mood of the one light source, so I adjusted the ISO on my camera; that controls the amount of light let in. I stood at the back of the room. The angle did not reveal the woman’s identity.

The doctor and her resident worked in tandem as a nurse assisted during the procedure.

“Are you doing OK?” the doctor asked the patient on the exam table. The woman acknowledged by nodding her head, yes.

At one point, the nurse held the patient’s hand and gently rubbed her head.

My Apple Watch began to vibrate.

“I need to leave soon,” said the text message from Gibson, my escort inside the clinic. She was waiting outside the exam room.

“Do you mind if I stay in here 5 more mins and maybe Angela can escort me out?” I wrote back.

“Unfortunately, that’s not the policy. I have to be with you,” she replied

“3 more minutes, okay?”

I wanted to stay until the end of the woman’s procedure, but after 3 minutes I tiptoed out of the room.

“You don’t have to go in! They murder babies!”

— Activists pleaded with women outside the clinic

I got in my rental car and drove to a shady parking spot. I needed to get confirmation that I had permission to photograph inside the Texas clinic the next morning — and find a way to get there that night.

I left a voicemail for the Andrea Gallegos, executive director of the clinic in San Antonio, and sent her a text message.

I waited. Ten minutes passed.

Then, a text from Andrea arrived. After a back and forth, she agreed to let us come to the clinic first thing in the morning. I headed to the airport. It would take me six hours to get from Albuquerque to San Antonio that night.

When I arrived at the Alamo Women’s Reproductive Services at 9 a.m. Friday, patients were already lined up outside the door.

Protesters were screaming through a megaphone on the sidewalk near the clinic.

“You don’t have to go in!” the activists pleaded with the women. “They murder babies!”

Molly and I were escorted into a back office to meet Dr. Alan Braid, the clinic’s owner. Then at 9:13, everything changed.

Braid’s daughter, Gallegos, poked her head in the door.

“It’s out. The decision’s out,” she said. “Full overturn.”

Braid cursed. Then he began to tear up. I was able to snap one frame of Braid as the tears came. Then, he looked at me sternly and said, “Come on!”

“The Supreme Court just overturned Roe vs. Wade. They’ve taken away your right to choose what to do with your body.”

— Dr. Alan Braid, clinic owner

I knew at that moment I had to put my camera down. I wanted to capture his emotions at that moment, but at the same time I didn’t want to anger Braid and hurt my chances of staying in the clinic longer.

My mind was racing. I needed to get to the waiting room, where patients were unaware of what had just happened.

It was a delicate balance for me. I promised the clinic administrator I would respect patient confidentiality and not photograph any patients who did not give us permission to do so. Even though this was a historic moment, I had to stick to my promise.

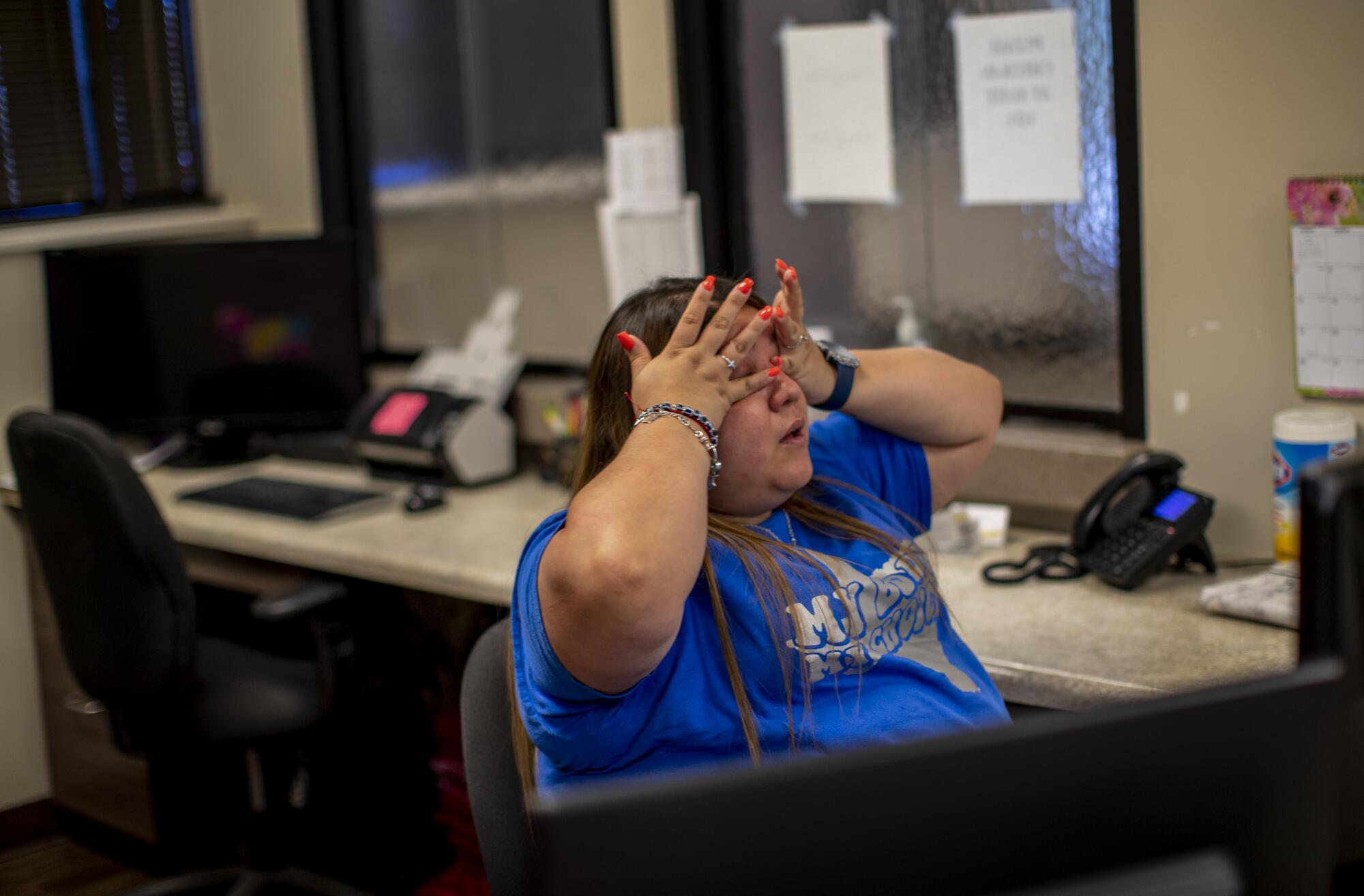

On my way to the waiting room, I photographed a staff member, who was visibly upset.

Braid entered the waiting room with Gallegos by his side. As I photographed Braid from across the room, patients put their heads down in distress as he spoke.

“The Supreme Court just overturned Roe vs. Wade. They’ve taken away your right to choose what to do with your body,” he said to the women.

“Unfortunately, my hands are tied,” Braid said, explaining the risks of challenging the law. “I can go to jail for life and be fined $100,000.”

The clinic could no longer provide abortion services.

I moved over to where I saw a patient, sitting with a blank stare. With my camera on silent mode, I photographed her. As she left the clinic, I followed her outside to get her name. She said I could use her first name, Liz.

As the early morning patients filed out of the clinic stunned, more filed in unaware that in abortion was illegal now in Texas.

Patient April Reese, 41, arrived exactly one hour after the decision. She already has three children.

An emotional staffer told her the news.

“So we have to go out of state?” Reese asked. “This is insane.”

Reese was about to leave when she noticed that the staffer who had helped her was crying. She hugged the staffer.

“You guys have done so much good work for people. So keep that in your heart,” Reese said. “Don’t give up the fight.”

Another patient, who was also upset, sat in a waiting room chair and cried as a staffer tried to comfort her. I photographed her through the glass in the receptionist’s area.

Two hours after Roe was overturned, the waiting room at Alamo Women’s Reproductive Services was empty.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.