- Share via

“On a pain scale of one to 10, it was a 10,” Scott Shirley recalled. “The worst pain I’ve ever felt.”

It was June 2020, and Shirley, a winemaker in Paso Robles, Calif., knew something was terribly wrong. He was going about his daily business when he doubled over with severe abdominal pain and a 103-degree fever. A doctor in the emergency room told him his left lung had collapsed.

But what ailed Shirley, now 50, wasn’t COVID-19: It was valley fever.

Officially known as coccidioidomycosis — or “cocci” for short — valley fever is a fungal infection that is transmitted in dust. In the United States, it has mostly plagued humans and animals in Arizona and California’s San Joaquin Valley, where the illness was first described as “San Joaquin Valley fever” more than a century ago.

But a disease that was confined to the arid Southwest for decades appears now to be spreading, with new cases being reported in Washington, Oregon and Utah. At the same time, infection rates are increasing, particularly in California, where rates have risen 800% since 2000.

Now, as health officers attempt to track this emerging infectious disease, researchers say climate change is largely responsible for its spread — much the way malaria, Zika virus and Lyme disease are believed to be getting worse because of global warming.

Cycles of extreme precipitation, along with worsening drought and heat, are creating more of the dangerous dust, researchers say, and worsening wildfires may also be fueling the spread. By the end of the century, valley fever may be a threat across the entire western United States, they say.

The West is experiencing its most severe megadrought in a millennium, according to a new study. Scientists say climate change is playing a major role.

“It’s emerging because we have increasing numbers, and it’s emerging because it’s being found in new areas,” said Nancy Crum, a physician with Scripps Health System in San Diego who published a review of valley fever in the journal Infectious Diseases and Therapy last month. “It’s a fungus in the soil, and so if you have really windy, dusty conditions, it can get from one area to the other.”

Shirley, who often works outside and around equipment that can kick up dust, said it’s impossible to pinpoint when and where he first inhaled the spores. In September 2020, he underwent surgery to scrape scar tissue from his collapsed lung like “an orange peel,” he said, but will live with the fungal infection for the rest of his life.

He’s not alone: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that there are about 150,000 valley fever cases in the United States each year, but most researchers say the number is much higher — closer to 350,000. In most of those cases, people who inhale the spores are asymptomatic or do not seek treatment. In some, the cases are missed because neither they nor their doctors know what to look for.

But what is undisputed is that weather patterns play a huge role in the spread of the disease, said Morgan Gorris, an Earth system scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and one of the leading researchers of the relationship between valley fever and climate change.

The ideal conditions for valley fever are wet winters followed by dry summers, she said. Coccidioides, the fungus that causes cocci, thrives in rain-soaked soil. When the soil dries and temperatures rise, the fungus breaks up into spores that can be launched into the air in billows of dust. In some cases, the spores can travel up to 75 miles.

Once inhaled, a spore changes into a spherical form that begins filling with many reproductive particles until it breaks open. The particles then spread into the lungs and other organs and repeat the process.

In California, climate change is already contributing to greater swings between intense rain and prolonged dryness. That can “cause almost ‘superblooms’ of the fungus,” Gorris said, priming the landscape for outbreaks of valley fever in the drier seasons.

The trend has already been observed in the state, with data from the California Department of Public Health showing case spikes after the wet winters of 2010 and 2018. The region overall has experienced the driest two decades in at least 1,200 years.

But increasing case counts are only one byproduct of that shift. The other is a change in where the fungus can actually live. In a 2019 study, Gorris and other researchers concluded that in a high-warming scenario — or one in which greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated — the number of affected states will jump from 12 to 17 by the year 2100, and the number of individual cases will grow by 50%.

Warming and drying trends driven by climate change “could allow more of the western United States to be able to host this fungus,” she said. “So ultimately, the fungus may spread, and it may put more people at risk for contracting valley fever.”

Like COVID-19, people infected with cocci can have extremely different symptoms. The disease typically affects the lungs and can present with respiratory symptoms such as cough, fever or chest pains, among other problems. More severe cases can lead to infections such as meningitis or pneumonia.

People who live and work among the dust are particularly vulnerable, with past outbreaks reported among inmate populations at Avenal State Prison in Kings County and Pleasant Valley State Prison in Fresno, both in the San Joaquin Valley.

In 2014, a western lowland gorilla living at the Los Angeles Zoo was treated for a severe case of valley fever, in which he lost about a fifth of his body weight. It has also killed gorillas at the San Francisco and San Diego zoos, and dogs are known to be susceptible.

Wildland firefighters are also increasingly at risk because much of their work involves digging in dirt and soil to draw containment lines. Some studies suggest that wildfire smoke can also carry the fungi.

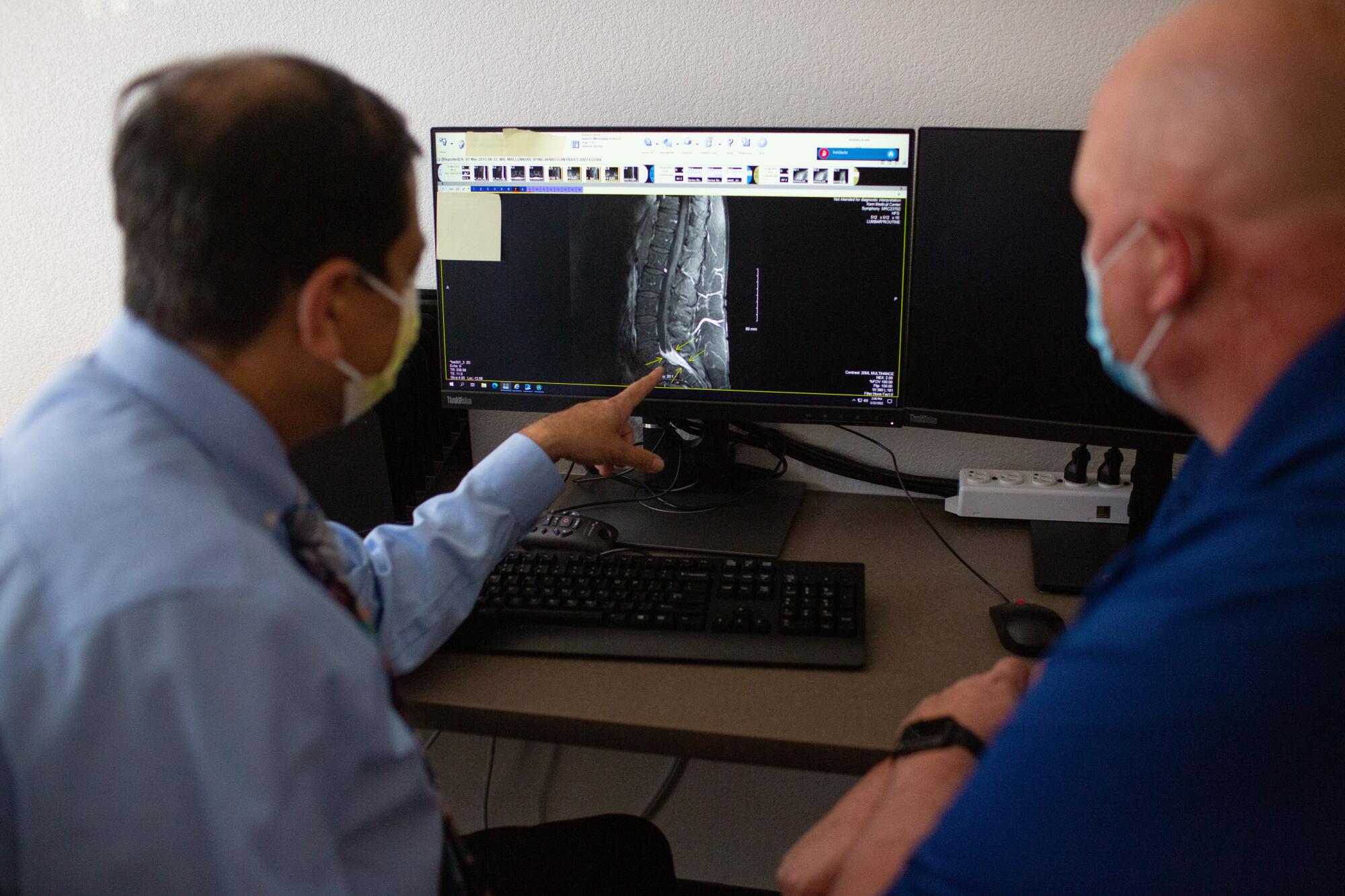

The problem has become so substantial that in 2015, Kern Medical in Bakersfield formed the Valley Fever Institute, which now sees about 1,500 unique patients each year, including Shirley. Valley fever research centers and programs have also been established at several universities.

Though population growth and human activity — such as industry, construction and development in the wildland-urban interface — are contributing to the spread of the disease, that alone can’t account for the skyrocketing cases in recent years, said Dr. Royce Johnson, medical director at the Valley Fever Institute.

Kern County’s population has just about doubled since the early 1980s, he said, but valley fever cases in the area have exploded nearly tenfold in that same time.

“It isn’t based on population, it isn’t because we build houses — there has to be more that’s changed than that,” Johnson said, “and we think it’s climate, weather.”

And while some groups can have higher risk factors for valley fever, including men, Black and Filipino people, people with diabetes and pregnant women, Johnson said the clinic has seen patients of “absolutely every kind of age, race and sex.”

Rob Purdie, the institute’s patient and program development coordinator, was also a patient himself. He was diagnosed with valley fever-meningitis in early 2012 after waking up on New Year’s Day with a “splitting horrible headache.”

Since then, his life has been a whirlwind of medications and complications, including pulmonary embolisms and failed antifungal treatments. For a while, he had to receive daily lumbar punctures to manage the pressure in his brain.

Eventually, doctors implanted a port beneath his scalp, allowing them to inject medication directly every 16 weeks. The treatment makes him violently ill.

“I call the last 10 years of my life ‘the lost decade,’ because I lost everything,” Purdie said. “Friends, financially, all that stuff changed. It changed my relationship with my children, it changed my relationship with my wife.... Depression, suicide, all that stuff goes through your head.”

Purdie began working at the institute in 2019 and remains an advocate for valley fever awareness and education. Though the severity of his case is rare, he said he considers himself lucky because he ended up with doctors who knew to look for valley fever and how to treat it.

“You can’t cure valley fever and you can’t prevent valley fever,” he said. “So it’s mitigation and treatment.”

California just suffered its driest January and February in more than a century. Water officials tell residents to brace for a third year of drought.

There are efforts underway to help reduce the spread, including a long-hoped-for vaccine, which researchers say is possible but in dire need of resources and funding.

And though official case numbers for 2020 and 2021 are still preliminary, some experts said face masks worn during the COVID-19 pandemic may have kept valley fever numbers lower by protecting people from inhaling the spores.

But awareness is also critical, because many people who present with symptoms may not have heard of valley fever, and clinicians outside the southwestern U.S. might not know to test for it. Some cases may also be misreported as COVID-19, because both are respiratory illnesses.

Wildlife may also contribute to the spread of valley fever by carrying it back to new regions, which then absorb the fungus into the soil when the animals die and decompose. Researchers argue this may occur more frequently as global warming drives species to relocate to cooler latitudes or higher elevations.

But weather and climate remain a dangerous catalyst for the dust. California and most of the western U.S. is experiencing a decades-long megadrought, and bouts of extreme weather — such as significant wet-dry swings — are becoming more common.

This winter, for example, saw a notably wet December in California followed by the driest January and February ever recorded in most of the state.

“Even if you aren’t in what’s considered a classic endemic location for valley fever, but you’re in the north or southwest, still think about it,” said Crum, of Scripps, “because you may be the first case diagnosed in your state or in your community.”

Shirley, the winemaker, said his case was more severe than most. But when asked whether he knew of any other people in Central Valley who have experienced valley fever, he barely hesitated.

“Let’s see: Three co-workers right now have it that I’m aware of; my dental hygienist; one of my daughters’ classmate’s parents; and one of our best friend’s 10-year-old child was just diagnosed,” he said.

After his lung operation in 2020, he slowly regained some strength and is now able to swim laps in the pool again. But the experience was incredibly challenging for him and his family, and his life will admittedly never be the same.

“I’m so thankful for each breath, and just to be able to take a walk around the block with my dog is quite a treat,” he said.

He wanted to share his valley fever story, he added, to let people know “how serious it is now — and how serious it is going to become.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.