Column: He had to leave Echo Park Lake and he’s still homeless. Is this what L.A. wants?

- Share via

It was exactly one year ago that David Busch-Lilly realized that life as he had come to know it was about to end.

It was a Friday morning, not far from the placid water of Echo Park Lake. Police officers and outreach workers had him surrounded — and they were getting impatient.

“They said, ‘David, we’re here to offer you housing,’” Busch-Lilly recalled.

For eight months, he had been living alongside roughly 200 other unhoused people in a sprawling, commune-like encampment they had built in the park. Busch-Lilly called it “beautiful” and city officials called a place of “squalor and filth.”

Whatever it was, the LAPD had helped break it up the previous two nights after the city ordered the park closed for repairs and homeless people sent away. Only Busch-Lilly and one other man, Ayman Ahmed, remained.

“Are you going to accept it?” the outreach workers pressed.

Busch-Lilly didn’t say what they wanted to hear, so he was taken into police custody. By Saturday morning, he was back on streets. By Saturday evening, he was back to sleeping in a tent.

Such recollections — and questions about the rationale for continuing to clear encampments — are the subject of a troubling new report on what happened at Echo Park Lake.

With the help of activists, researchers at the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy found that only 17 people received long-term housing out of 183 identified as living at the encampment.

An additional 48 are still on a waiting list, 15 were unsuccessfully housed, six died and at least 15 went back to living on the streets like Busch-Lilly did. Another 82 people basically disappeared, as the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority has lost communication with them.

“Politicians very loudly claimed that all displaced residents would be in stable permanent housing within a year,” Ananya Roy, director of the Luskin Institute, said during a news conference Thursday. “Echo Park Lake has become both the exemplar and blueprint of this kind of displacement.”

Of the 183 people who were on the ‘Echo Park Lake placements list,’ only 17 were placed in some form of long-term housing, researchers found.

Many of those who had to leave agreed to move into hotels under Project Roomkey, a state program designed to let unhoused people avoid COVID-19 by staying safe in private rooms.

They were told it would be a pathway to permanent housing. But for too many, that’s not what happened.

It took less than week for some people to return to the streets, put off by the strict curfews, isolation and lack of privacy. Others ended up like Olga, who told me last April how she was being bounced from hotel to hotel, each one farther away from anyone she knew.

Busch-Lilly talks about a friend from Echo Park Lake who landed at the L.A. Grand Hotel. He had trauma from years of homelessness and no access to therapy. So he sometimes got aggressive when he was told what he could and could not do.

“He would stand up, stand his ground. He wouldn’t back down,” Busch-Lilly told me. “They booted him out. The last time I talked to him, he was camped in a tent by the side of the freeway.”

::

When homeless activists and others are shouting down mayoral candidates at forums and debates, this is often what they are shouting about. I know it can be hard to tell sometimes between all the obscenities and insults.

They want to shame the politicians as “liars” for passing off temporary and emergency shelter situations, whether hotel rooms or tiny homes, as housing.

They want an explanation for supporting the clearing of encampments, even when there isn’t enough long-term housing for every homeless person forced to move. They want to point out the hypocrisy of the city holding up Echo Park Lake as some sort of “successful” model to be replicated.

And, quite frankly, they have a point. The way Los Angeles conducts cleanups of encampments — both large and small — is often a disorganized, bureaucratic mess that does nothing to bolster any unhoused person’s trust in the system.

Still, Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office continued to praise the cleanup of Echo Park Lake, despite the UCLA report. L.A. City Councilman Mitch O’Farrell, meanwhile, disputed most of its findings.

Part of the problem is that, at least politically, the definition of “successful” has changed.

Activists want to solve the actual problem of homelessness by getting people into long-term housing. However, voters have increasingly settled for the far faster and far easier option of solving encampments, getting unhoused people out of their sight.

Take, for example, the findings of a recent poll conducted by the Los Angeles Business Council Institute in cooperation with The Times. Asked whether elected officials should focus on “short-term shelter sites” or “long-term housing for homeless people with services,” voters by 57% to 30% said to go for the former. Two years ago, the opinions were nearly evenly divided.

This means the problem isn’t so much the politicians. The problem is public opinion. Politicians are just doing what politicians so often do, which is follow the polling. It’s not particularly brave. But it’s as true for the top mayoral candidates in Los Angeles as it is for Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“People have had it. They’re just exhausted,” Newsom told KQED this week. “They can’t take what’s happening on the streets and sidewalks. They can’t take what’s happening in encampments and tents.”

That leaves advocates and activists like Busch-Lilly who want elected officials to do more than just address visible homelessness with the tough task of swaying public opinion. Of tapping into that reservoir of empathy that’s drying up faster than the water in Lake Mead.

I’d argue that heckling mayoral candidates and shutting down debates and forums is an idiotic and counterproductive way to do that — in addition to being, as I wrote earlier this week, terrible for the democratic process.

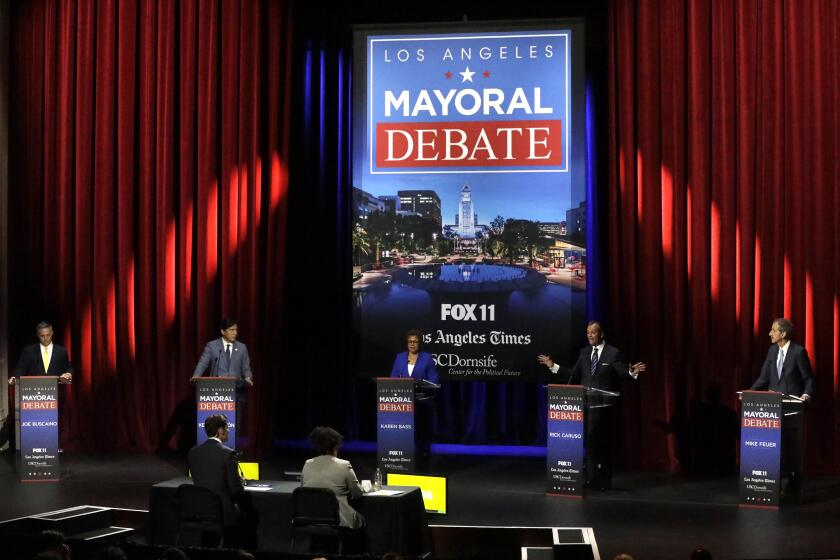

For the first time on TV, top candidates were able to talk without being shouted down by hecklers. It required tight rules at USC’s Bovard Auditorium.

But I asked Busch-Lilly what he thought.

At 66, he’s been unhoused for some 20 years and a fixture in the close-knit circles of homelessness activism for almost as long. He’s participated in plenty of protests and, because of that, has had some minor run-ins with police.

“I think that it’s always better when we get past the shouting and we get to the issues,” he said. “But a lot of times, polite discussion in this city has not gotten to the issues.”

Busch-Lilly thought some more.

“Demonstrators are angry because they know about these things. They’ve got the data to back it up,” he said. “And politicians are running to safe, moderated debates where they don’t have to face these things. It’s too easy. Politicians in this city right now need to face some tough questions.”

He insists that none of the activists he works with are violent. He wants the city to raise taxes or the state to dip into the surplus to pay for real solutions for those living on the streets. In the meantime, he supports homeless people who want to remain in their tents until an “adequate alternative” — housing, not hotels — becomes available.

“Politicians in this city feel threatened not by us,” Busch-Lilly insisted, “but from having to face the truths about homeless oppression by them.”

These days, the time he spent in jail after being booted from Echo Park Lake last March is mostly a distant memory.

After pitching his tent for a while, someone gave him a vehicle. That’s where he lives now. He has outfitted it with solar panels and inscribed it with positive mottoes, including “Always Be Compassion” scrawled across the hood.

He often parks in Echo Park.

That eight months of his life at the encampment, Busch-Lilly told me wistfully, “was the first time in almost 20 years that I was ever able to not sleep on a doorstep in a sleeping bag or pitch a tent anywhere other than the sidewalk.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.