Buddhists confront anti-Asian violence with peaceful perseverance

- Share via

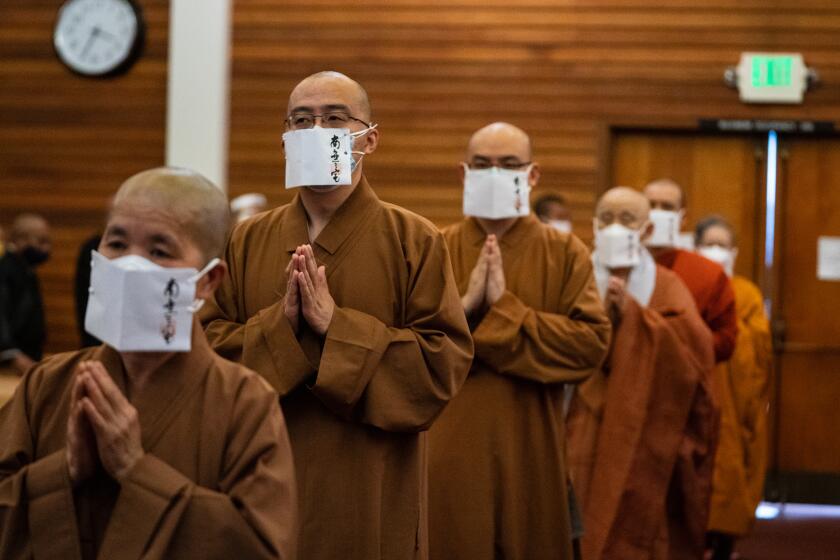

One by one, the Buddhist priests bowed before the altar at the Higashi Honganji Buddhist Temple in Little Tokyo, wearing robes of yellow, orange and black.

Accompanied by the chanting of the Heart Sutra in Korean, they dipped a paintbrush into a bowl of golden lacquer to gently fill in the cracks of a white ceramic lotus that had been handmade for the occasion.

The ritual, which took place last May, was drenched in meaning. The lotus flower represented the purity and potential of the Buddha’s awakening. The repairing of the cracked ceramic lotus, a Japanese art known as kintsugi, was a symbol of the collective effort to heal the wounds of religious bigotry.

Here, just 49 days after the March 16, 2021, killing of eight people in an Atlanta-area shooting rampage, including six women of Asian descent, was a symbolic effort to turn brokenness into beauty.

The timing was also significant: The 49th day after death represents the end of the bardo, an intermediate stage between life and rebirth in some Buddhist traditions.

For the record:

2:00 p.m. March 18, 2022An earlier version of this story suggested May We Gather was the first event to draw together followers of every major school of Buddhism for the first time since the tradition was founded. It was not.

The ceremony was part of May We Gather, a historic event that drew together followers from all schools of Buddhism.

Southern California is the world’s only place where all major schools of Buddhism are represented — and followers recently gathered for what’s believed to be the first time to offer healing against anti-Asian bias and other racial hate.

“I had never seen anything like it before, and I don’t think there has been anything like it before,” said Indigo Som, co-director of the Asian American Buddhist Working Group, which formed a year ago. “It was a specific response to an attack on our community that was multi-lineage, pan-Asian and pan-Buddhist.”

May We Gather served another purpose: helping to jump-start a conversation among a diverse population of Buddhists about how leaders and institutions can respond to the anti-Asian violence that has long been part of American history, and which has been exacerbated by the pandemic over the last two years.

“So much of what has happened after the event is the acknowledgment that there is this shared experience, and that we have all, in different ways, confronted racism and white supremacy in America,” said Nalika Gajaweera, a research anthropologist at the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at USC. “We may not respond in a coherent voice, but we’re having a conversation.”

Scholars say the history of anti-Asian violence in the United States has long been intertwined with anti-Buddhist sentiment. As a non-Christian faith, it was considered heathen, pagan and anti-American when it was introduced to the United States by Chinese laborers in the 1850s.

In the years after the Civil War, Asian Americans were denied voting rights in part because they were seen as too different — including their spiritual traditions — to be assimilated into American culture. In the 1940s, Japanese Buddhist priests were classified as a threat to national security in the prelude to America’s entry into World War II.

Funie Hsu, a professor of American Studies at San Jose State University, said that another type of anti-Asian violence occurred during the 1960s and subsequent decades, as counterculture Westerners, rejecting a society they viewed as corrupted by materialism and militarism, turned to Eastern religions to seek enlightenment. As Buddhist books, magazines and retreat centers began to highlight the work of white converts, and spiritual rebels such as Jack Kerouac popularized the ideal of the wandering, truth-seeking “dharma bum,” some Asian Americans felt marginalized in their own hereditary religion.

“In my experience, the way that Asian Americans have suffered racism the most in the United States is not only through hate and exclusionary laws, but by erasure and invisibilization,” said Mushim Patricia Ikeda, a teacher at the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland who spent 25 years trying to build bridges between hereditary Buddhist communities and largely white convert groups. It was an effort that she said largely failed.

Asian and Asian American Buddhists have been victims of religious hate in recent years as well. Buddhist temples were vandalized, including six in Santa Ana and Westminster and one in Little Tokyo, after the start of the pandemic. At one temple in Santa Ana, a person spray-painted the word “Jesus” on a stone statue of the Buddha.

“The damage to property is not what keeps us up at night or what bothers us the most. It’s the hate crime in itself and the negative impact to interfaith relations in our community,” the Venerable Vien Hay of the Dieu Ngu Temple, one of the vandalized temples in Westminster, told The Times at the time.

“The history of Buddhism in America is confronting anti-Asian violence,” Hsu said.

As Asian American Buddhist leaders grapple with the current wave of violence in the wake of the pandemic, many are turning to lessons from their history and religion to inspire resilience in their sanghas, or communities.

“Policy and political solutions are important, but in the face of the suffering people are experiencing, tending to their spirit and giving them fortitude is probably the most important thing religion can do,” said the Rev. Cristina Moon of Daihonzan Chozen-Ji International Zen Dojo in Honolulu.

One way to do that is to help individual Buddhist communities remember the courage and drive that it took for their predecessors to come to America and make a better future for themselves in the face of discrimination and violence, she said.

“Just reminding people that we’ve been through tough times before and we persevered by holding on to who we are and staying true to that faith,” she said.

Som, who co-facilitates the Asian American Deep Refuge Sangha at the East Bay Meditation Center, agreed.

“Asian Americans and Asian American Buddhists specifically have been under attack the whole time we’ve been in this country, and there’s a whole story about people being pressured to convert to Christianity to be ‘more American,’” she said. Maintaining the dharma — Buddhist teachings — maintaining the faith, and maintaining a temple is “already pushing against the violence, the erasure and the racism.”

Gajaweera, the anthropologist and co-director of the Asian American Buddhist Working Group along with Som, Louije Kim and Dorothy Imagire, elaborated: “It might not seem like activism, but it is the day-to-day activism of keeping your doors open and supporting your community.”

Brother Phap Dung, a dharma teacher at Deer Park Monastery in Escondido, said between 200 and 300 members of the public come to the mountain monastery each Sunday to take refuge from the discrimination, loneliness and the basic fear and anxiety that is pervading society.

Thich Nhat Hanh, a Buddhist monk from Vietnam, brought mindfulness to the West.

“We don’t just look out for Buddhists,” he said. “We try to take care of all the people who are facing discrimination — African Americans, Latinos, gay and lesbian, LGBTQ.”

Monastics offer support by just being there, listening, taking visitors on hikes, showing them a sunset and reminding them of the wonders of life.

“That can also be good medicine for taking care of the mental toxins and discrimination we have received from others,” he said. “Finding ways to joy and wonder helps us not be overwhelmed and monopolized by the hate in society.”

Hsu said she has also found solace in the Buddhist idea of Indra’s net: an infinite web of connection with a single, shining jewel at each point of connection. Each jewel reflects every other jewel in the web, and whatever affects one jewel affects them all.

“That was one of the ideas we were trying to emphasize with May We Gather,” she said. “That we are not separate from each other.”

For the one-year anniversary of the Georgia shooting rampage, the organizers of May We Gather published reflections from Buddhist leaders and practitioners inspired by the dharma. Contributions came in from Buddhists in California, Washington, Oregon, Maine, Illinois, New York, Massachusetts, Canada and elsewhere.

They expressed sorrow for those lost — and gratitude for the opportunity to grieve together.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.