Why it’s been so warm and windy in Southern California this winter

- Share via

The official stats are in: January and February were the driest first two months of the year on record across much of California. Those months should normally be the wettest period of the year.

February was also unusually warm. In Southern California, the warm readings were repeatedly accompanied by Santa Ana winds. These conditions dried out vegetation after an uncommonly wet December in the state and spurred winter wildfires such as the Emerald fire in Laguna Beach.

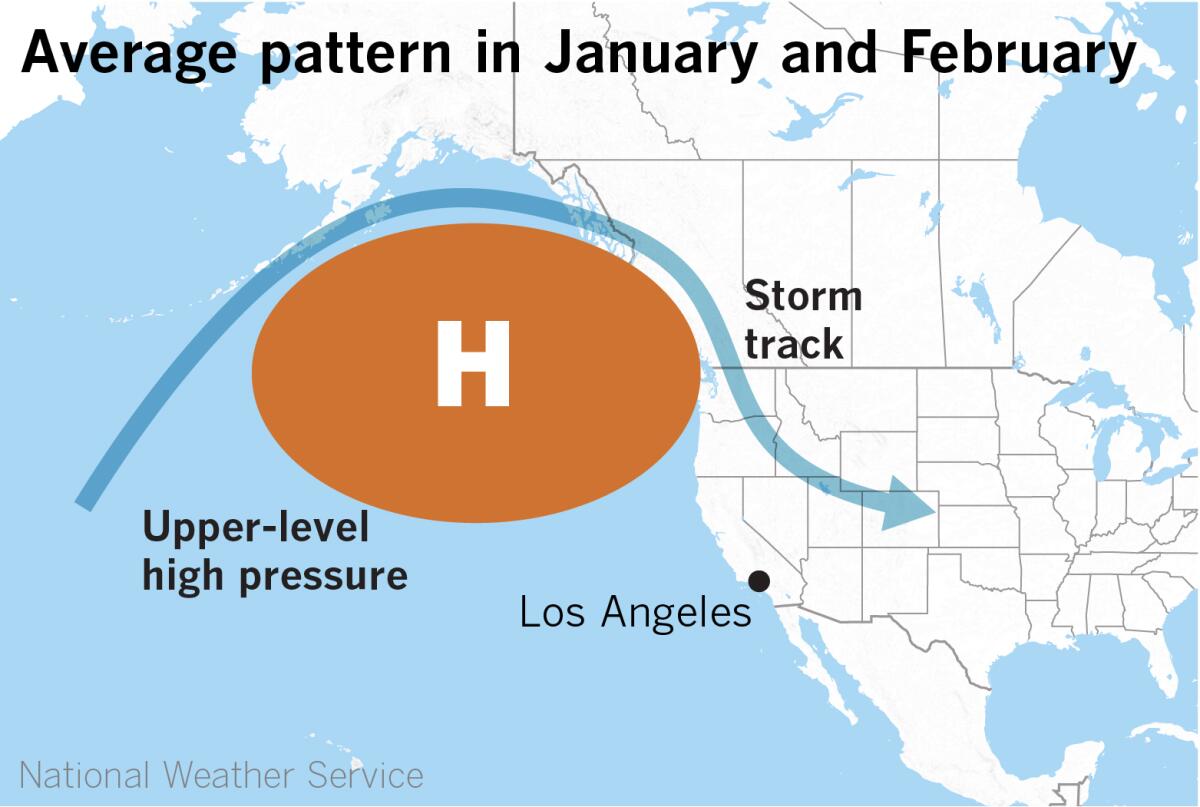

After the December deluges, the atmospheric phenomenon nicknamed the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge by climate scientist Daniel Swain, moved back into position in the eastern Pacific. This big lump of high pressure pushed the jet stream or storm track inland, and set the stage for heat advisories during Super Bowl week in Los Angeles.

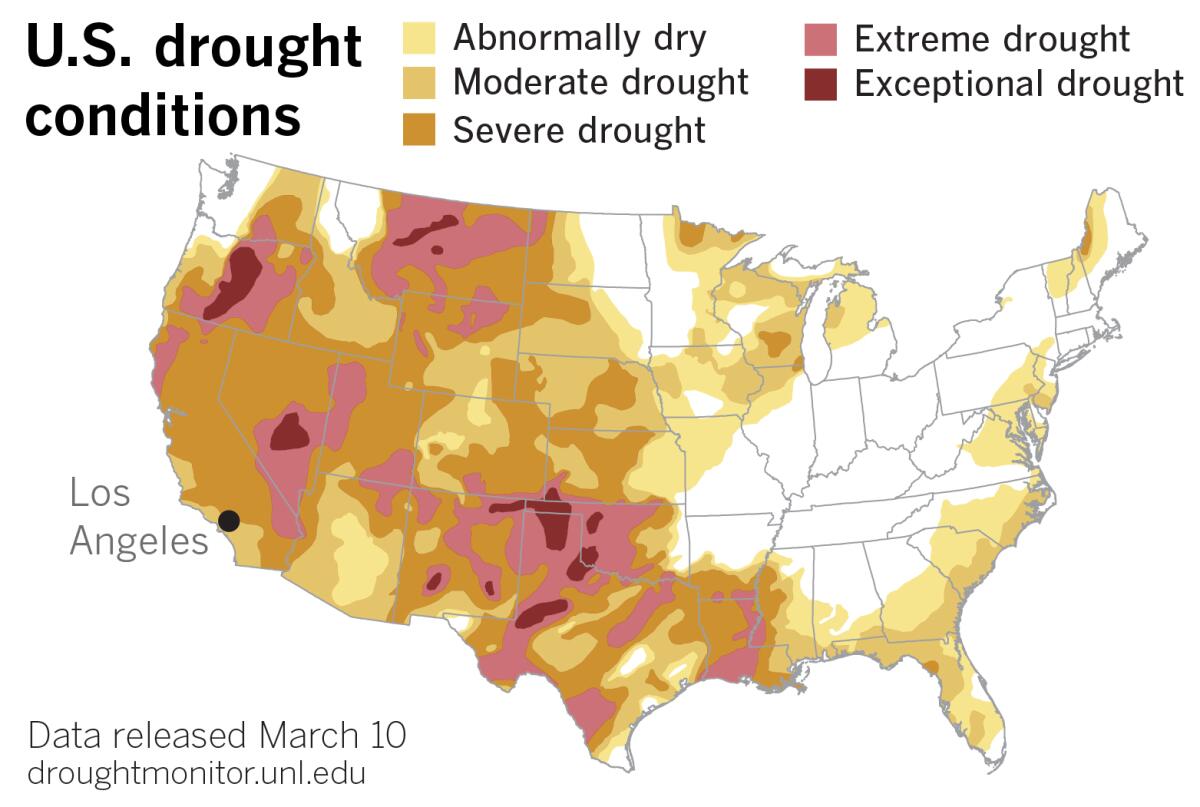

So California and the Southwest returned to what is more like the script for a second consecutive La Niña winter, amplified by climate change, and raising fears of a third year of record drought.

This high-pressure pattern that promotes clear skies and warm, dry winter weather also provides the perfect setup for Santa Ana winds. There have been at least 20 Santa Anas since September, according to Alex Tardy, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in San Diego.

Slight shifts in the pattern can make all the difference. During December, the huge high-pressure system had backed off to the west, allowing the storm track to dig southward to California. Storms from the Gulf of Alaska hurtled down the West Coast and tapped into tropical moisture from atmospheric rivers at least three times.

Since then, that high-pressure area has mainly shifted back to the east, said Tardy, shutting off the wet storms. But a slight shift to the west brought a storm that dropped a foot of snow on Big Bear during the first weekend of March. It’s a very fine line between wind and precipitation in this pattern, he explained.

This warm air mass is a much stronger block than you would normally expect in the Pacific in January and February, Tardy explained. In fact, he described the weather pattern during Super Bowl week as very similar to the one that brought record heat to the West Coast last summer. The difference, though, is in the magnitude. Because of the season, it couldn’t be as strong as it is during the summer.

Nevertheless, this blocking high has been pushing storms away to the north and east, and for the most part keeping Southern California dry, windy and unseasonably warm. Its position has resulted in a succession of “inside sliders,” or storms that have been forced down the east side of the ridge over the interior West.

If these systems were able to come down the West Coast over water, we would probably be talking about a series of wet storms, but since they come down over land, they’re dry.

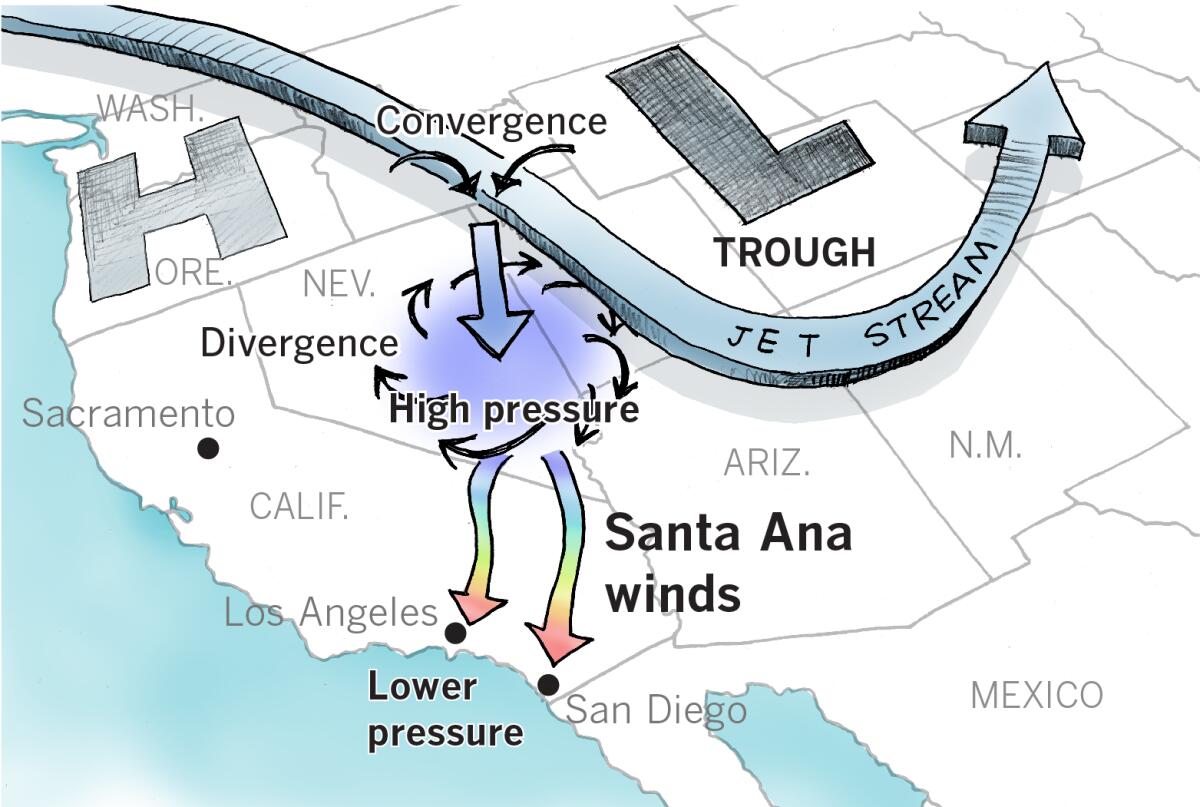

As upper troughs pass, they’re followed by high pressure building at the surface. The trough, which moves west to east as part of the jet stream, typically generates sundowner winds in southern Santa Barbara County, then north winds through the Interstate 5 corridor, culminating in the surface high setting up over the interior, often Nevada, and generating the Southland’s infamous northeasterly offshore Santa Ana winds.

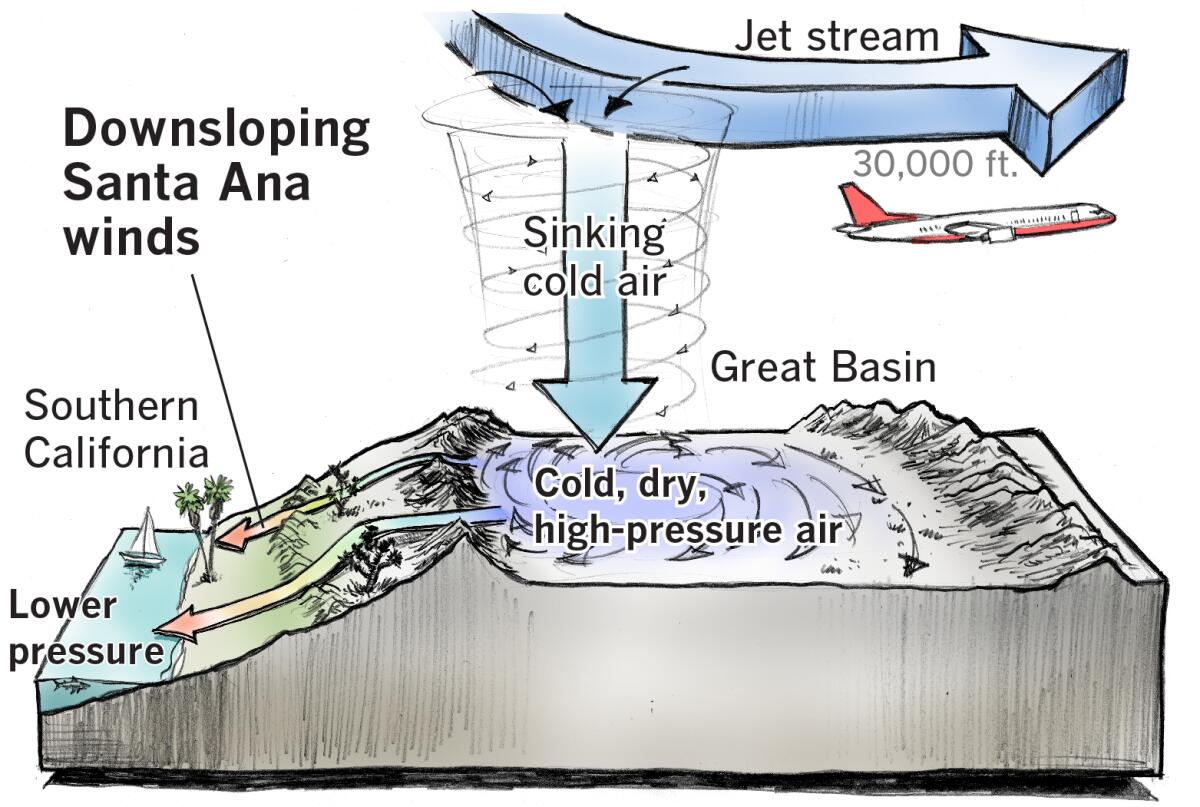

In this pattern, cold air high in the troposphere, on the west side of the trough, converges and sinks. It starts out at around 30,000 feet, where airliners cruise, and descends to the surface. This creates an area of dry, cold, high-pressure air, pooling in a part of the inland West called the Great Basin, which acts like a big bowl whose sides are formed by mountain ranges. The cold air circulates clockwise and, because the atmosphere is always seeking to restore equilibrium, diverges and flows toward lower pressure.

That lower pressure is found off the Southern California coast. The pressure gradient, or difference, between the high pressure air in the Great Basin and the lower pressure air at the coast creates the Santa Ana winds. A temperature gradient also can come into play. As meteorologist Miguel Miller, also from the San Diego weather service office, points out, a temperature gradient is proportional to the pressure gradient, and a steep temperature gradient steepens the pressure gradient.

This wintry interior air mass is significantly colder than the air at sea level in Southern California. Because cold air is heavier than warm air, gravity plays a role. The Great Basin’s valleys range in elevation from 2,000 to 6,000 feet. So as this air descends toward lower pressure at the coast, it heats up and dries out due to compression.

A bicycle tire pump provides a good illustration of this principle: As you compress the air in it, the pump cylinder warms up noticeably.

“Often, the explanation that Santa Ana winds are hot because they come from the desert, a normally hot place, is false,” said Miller. “It’s not just a simple matter of hot air moving from one place to another.”

The sinking air rises in temperature by 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit for each 1,000 feet that it descends. This is called the lapse rate. Air that flows from a 4,500-foot mountain pass down to the ocean, for example, would warm by almost 25 degrees.

Early in the season, the high-pressure air in the Great Basin starts out warmer, so the addition of compressional heating can make for winds that feel hot like a hair dryer. Later in the season — late fall and winter — the jet stream comes farther down out of Canada and feeds much colder Arctic air into the interior West. That colder, denser air can generate stronger winds, even though they may not be as oven-hot as in the early fall. These later-season winds are more likely to have upper-level support — meaning winds higher in the troposphere may influence the winds at the surface through a sort of chain reaction. The cooler, denser air helps drive those winds aloft to the surface because of subsidence or sinking, Miller adds.

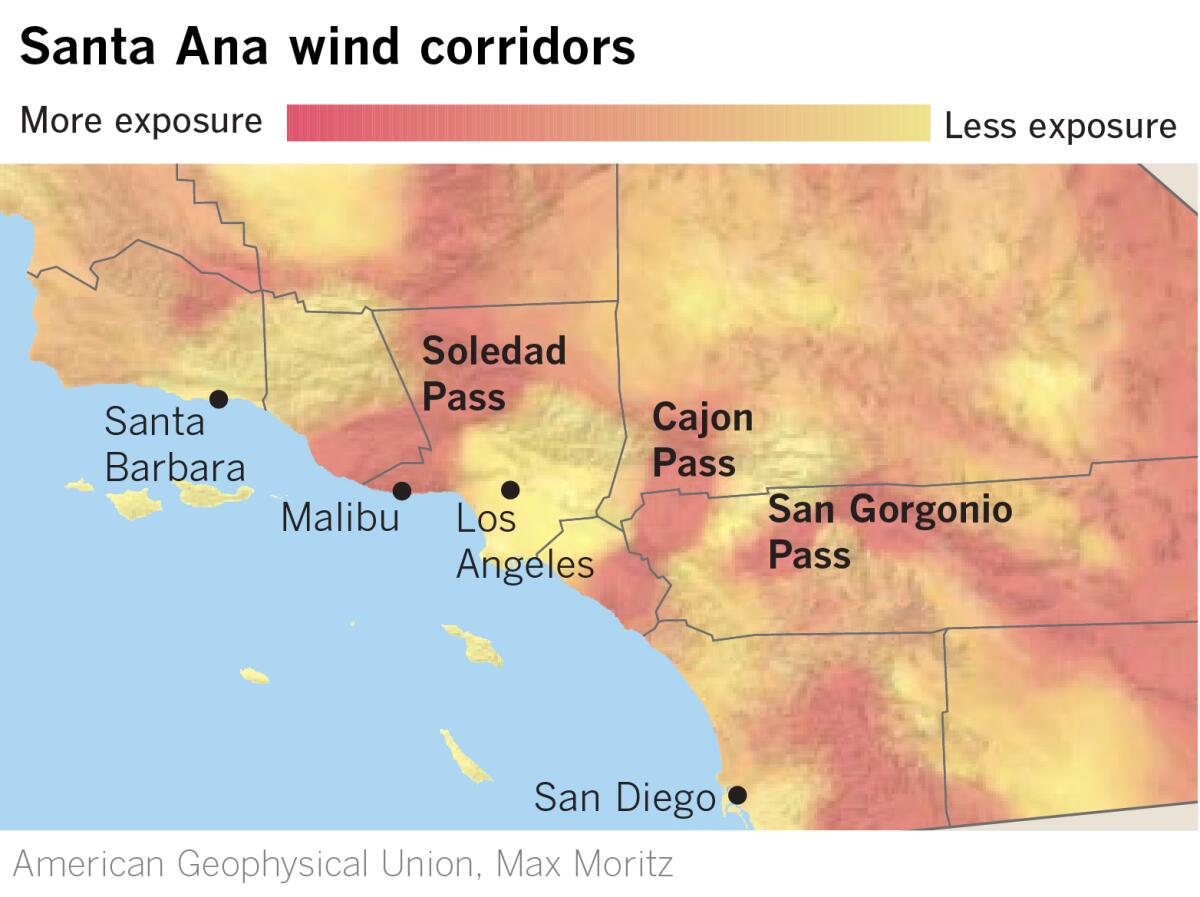

In addition to the pressure gradient as a driver, winds accelerate as they are squeezed through canyons and passes. Chokepoints such as Soledad Pass, Cajon Pass and San Gorgonio Pass act like nozzles on a garden hose, increasing wind speed through a Venturi effect. Winds also lift over and through crenulated ridgelines and careen downhill, accelerating with gravity on the lee sides of mountains, which is the side facing the ocean and densely populated coastal Southern California. The strongest winds reach all the way to the beaches, often thrilling surfers by hollowing out waves, and can sometimes cause havoc across the channel in harbors such as Avalon on Santa Catalina Island.

The average Santa Ana event lasts about two to three days, Tardy points out, starting in the L.A. and Ontario area and ending in the San Diego County mountains, where the winds may eventually blow through the Interstate 8 corridor.

This year, the winds have been virtually back-to-back events. Each passing dry storm system is followed by desiccating winds lasting two or three days.

It’s no wonder that it has seemed constantly windy this fall and winter. If there have been 20 Santa Anas and each event lasts two or three days, that translates to 40 to 60 days of wind in the Southland.

The big blocking high may have given Angelenos a chance to rock some exceptionally warm weather for out-of-town visitors during Super Bowl week, but it also unfortunately is tailor-made for continuation of the West’s record drought.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.