Todd Spitzer’s missteps could provide opening for opponents in O.C. DA’s race

- Share via

In his hometown of Los Angeles, Todd Spitzer’s conservatism would have made a political career difficult.

After moving to Orange County, Spitzer thrived, winning every election he entered for more than two decades, from school board to county supervisor to state assembly to district attorney.

Now, as he campaigns for a second term as O.C.’s top prosecutor, Spitzer finds himself in unfamiliar territory — more politically vulnerable than he has been in a long time.

In part, the challenges for Spitzer are demographic. Orange County has evolved from its John Wayne-style law and order roots to a place that twice voted against Donald Trump and is majority Latino and Asian.

Spitzer, a Republican, is also limping from self-inflicted wounds after racist comments he made surfaced last month, along with a video of him saying the N-word while quoting a hate crime defendant.

All of this could strengthen the chances of his opponents, Peter Hardin, Mike Jacobs and Bryan Chehock, in the June primary.

Hardin, a Marine Corp. veteran and Democrat, is attacking Spitzer from the left, while Jacobs, a Republican, is selling himself as a steady hand who can reform the office where he spent nearly three decades. Both men are former O.C. prosecutors.

Chehock, an attorney who works in San Diego, is the newest entrant in the race.

“Running a Republican-style campaign for any office in Orange County is like a paint by numbers. It’s yours to lose,” said Matthew Lesenyie, an assistant professor of political science at Cal State Long Beach. “What’s different this time is that these issues have created an opening for other candidates. I just don’t think Spitzer can wave his hand at it.”

In response to Spitzer’s racist comments, some political groups and district attorneys in other jurisdictions pulled back their endorsements of him. Protesters gathered outside Spitzer’s office in Santa Ana to call for his resignation, and the county’s Office of Independent Review launched a probe.

With a primary election against two former prosecutors set for June, it is unclear how much the comments will ultimately hurt Spitzer, especially in O.C., where tough-on-crime candidates are typically popular.

Spitzer made the comments in October during a meeting of top prosecutors on whether to seek the death penalty against a Black defendant. Prosecutors believe the defendant, Jamon Buggs, shot two people because of jealousy over an ex-girlfriend, who is white.

Spitzer said at the meeting that he knows “many black people who get themselves out of their bad circumstances and bad situations by only dating white women,” according to a memo by former prosecutor Ebrahim Baytieh.

Spitzer has apologized for the comments, saying he “used an example that was insensitive.”

He said Baytieh misquoted him and the motivation he ascribed to Black men for dating white women was to “improve their stature in the community.”

Hardin, who entered the race roughly a year ago, said he is concerned that Spitzer’s comments could “cast a shadow over every prosecution involving a person of color.”

Hardin has said he would not seek the death penalty, end cash bail and pull back on charging children as adults. His ideas align him with some of the more progressive district attorneys in the nation and contrast starkly with Spitzer, who has run a campaign largely centered on enhancing public safety by punishing criminals.

“We need to put safety over tough talk and headlines,” Hardin said. “We don’t honor today’s victims and survivors of crime by creating more and more for our future generations.”

Jacobs, who has 141 jury trials under his belt, said his experience will help him refocus an office plagued by scandal.

“He talks a tough conservative game, but I’ve been around, and I know what cases should be and how you’re supposed to handle them,” Jacobs said of Spitzer. “It’s not being done right.”

Chehock, a San Clemente resident, told The Times when reached by phone on Friday that he was at work and couldn’t immediately discuss the campaign.

Early support for Hardin’s candidacy may be a sign that O.C.’s approach to law enforcement could change.

Hardin has raised more than $644,000, according to recent campaign finance filings. He has secured endorsements from the Democratic Party of Orange County and several Orange County congressional Democrats.

But even in liberal Los Angeles and San Francisco, progressive prosecutors who have promised to dismantle mass incarceration have drawn intense criticism. L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón is facing a second attempt to recall him by voters who believe his policies have led to increases in crime.

Spitzer has raised more than $771,000 so far and has the backing of organizations including the Orange County Republican Party and several unions, including one that represents prosecutors in his office.

Jacobs, who entered the race in late January, and Chehock have not filed any fundraising paperwork.

Spitzer and Hardin have traded barbs for months, with a focus on undermining each other’s character and morals.

In a series of campaign videos, Spitzer labels Hardin a “predator” who preyed on women for sex while working as a prosecutor.

He has also questioned Hardin’s departure from the military, alleging that he violated rules against adultery.

Hardin has said he was going through a divorce at the time and was given an honorable discharge. He has denied any improper behavior at the O.C. district attorney’s office and has criticized Spitzer’s tenure as being “defined by scandal.”

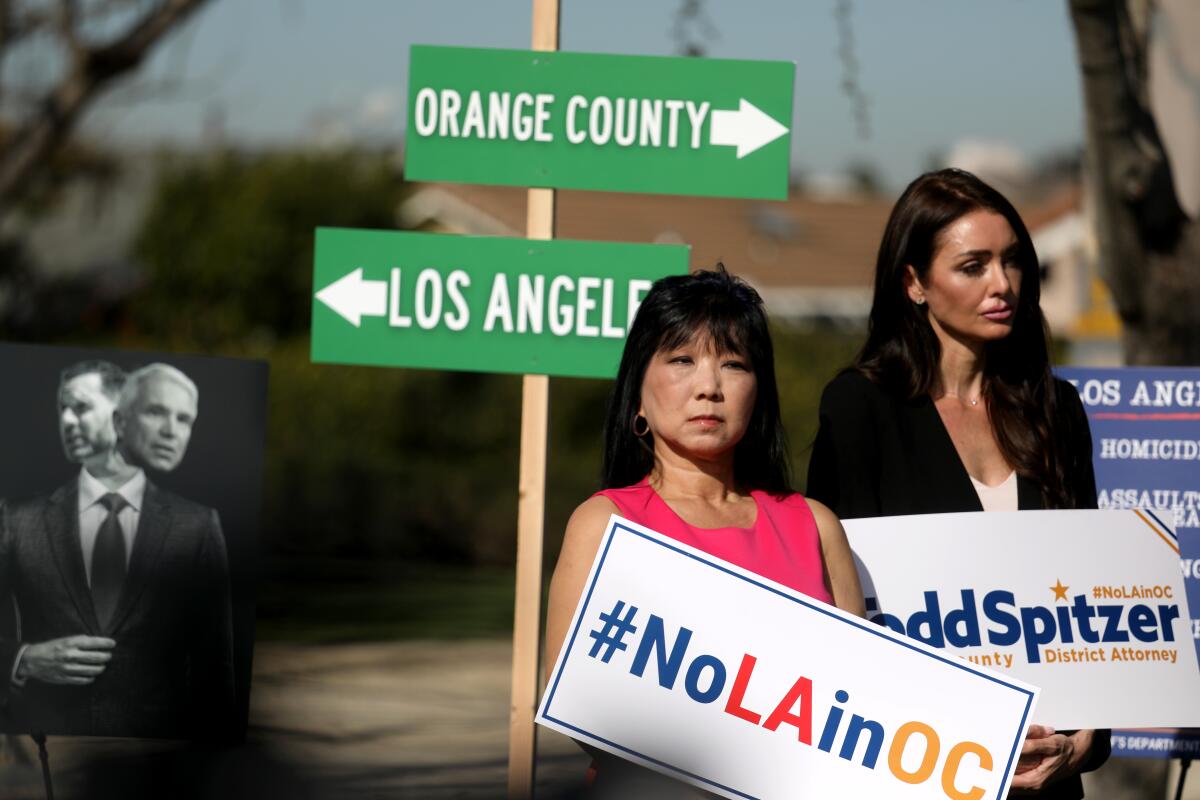

At his campaign launch in January, Spitzer stood at the border of Los Angeles and Orange counties, straddling the line that separates them. Behind him was a banner that said “LA” on one side and “OC” on the other.

Supporters held signs displaying his campaign hashtag, #NoLAinOC.

“Do you want to remain the safest county in America? Or do you want to trade that off and take a risk with somebody who has never been elected, has no track record, no voting record ... is that what you’re willing to risk for the public safety of Orange County?” Spitzer asked the crowd, referring to Hardin.

Jodi Balma, a political science professor at Fullerton College, said Spitzer is trying to present an exceptionalism that draws on a hazy, Beach Boys version of O.C.’s past.

“It’s the idea that Orange County is better because we’re not other places,” she said. “Todd Spitzer is trying to sell the idea that he stands between that version of Orange County and the apocalyptic dystopian Los Angeles that those same people fear.”

In Orange County, home to roughly 3.2 million people, violent crime and property crime were on the rise in 2020, according to data from the Department of Justice. Early numbers indicate a similar trend last year.

But crime has not been as much of a concern in O.C. as in L.A. County, where a spike in homicides during the pandemic has stoked voters’ fears and is shaping the L.A. mayor’s race as well as the effort to recall Gascón.

When Spitzer beat Tony Rackauckas in 2018, he vowed to bring a new era of reform after a scandal involving the use of jailhouse informants. He also promised a focus on victims’ rights.

He launched new initiatives, creating a hate crime unit and a recidivism reduction unit aimed to address issues, like mental health, addiction and homelessness, that often lead to people being repeatedly charged with crimes.

But the issues during his tenure are not limited to his comments about Black men’s dating habits and his parroting of the N-word, which occurred during a speech to the Iranian American Bar Assn. in November 2019.

Several female employees in the D.A.’s office have sued the county, alleging that a former high-level supervisor sexually harassed them and that Spitzer retaliated against them after the abuse came to light.

Spitzer also faced scrutiny after he attempted to dismiss charges in a high profile Newport Beach rape case. A judge, in a rare move, denied his request and ordered the case be turned over to the California attorney general’s office.

Orange County D.A. says he’ll drop all charges against a Newport Beach doctor and his girlfriend accused of drugging and sexually assaulting women.

Tracy Miller, a former senior assistant D.A., filed a claim last month alleging she was pushed out of her job for standing up to Spitzer about harassment and other issues in the office. She also alleged that Spitzer made improper contact with a family member of a victim tied to a high-profile murder case.

Early on, some predicted that Spitzer had a good shot of taking at least 50% of the vote and winning outright in the primary. Now, with the series of scandals and the two late entrants into the race, Spitzer may be headed for a runoff in the fall, experts say.

Spitzer says he’s up for the fight.

“If you’re not out there every single day slugging it out and showing people why you deserve this and why you want it, the voters will know,” Spitzer said. “You have to go to the mat every single day in this job.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.