Column: The anger that erupted in Venice in 2018 is shaping the race for Mike Bonin’s seat in 2022

- Share via

Traci Park, one of several candidates running to replace Westside L.A. City Councilman Mike Bonin, vividly recalls the raucous community meeting in Venice back in October 2018, when residents unloaded on Bonin, Mayor Eric Garcetti and LAPD Chief Michel Moore.

“It was very heated and, frankly, uncomfortable in many ways,” said Park, who told me she turned to a guy who was screaming at Moore and told him to knock it off.

And yet Park, like others, was at a breaking point.

The conversation about homelessness in Venice and the rest of Los Angeles had gone on for years, with a growing number of encampments, blocked sidewalks and a general sense of greater chaos, human suffering and public safety issues. And Park didn’t trust the latest promise from Bonin and City Hall: that a planned facility known as bridge housing, one of more than two dozen citywide, would help turn things around in Venice.

“The community was up in arms over the fact that this was being brought into a location where there are children present, and right in the heart of the core of Venice,” Park said.

She sized up Bonin’s response to his detractors like this: “Just palpable disregard for valid concerns, and little to nothing to address real questions about children and public access to our beach and the safety of our community.”

Now a half-dozen candidates are primed to make a run at Bonin’s seat. Bonin pushed hard to get people into various types of housing, with some success as well as periodic neighborhood opposition. A recent recall effort fell short but demonstrated sinking support, and Bonin said several days ago that he’s not interested in a third term, citing depression as one reason.

In some ways, that 2018 meeting was a window on things to come, with escalating citywide frustration on all fronts and the homeless death toll rising above three daily. Advocates still scream for the unhoused to get more help. The housed still want their sidewalks back.

“This is issue one, two and three,” said Greg Good, a candidate to replace Bonin.

The same is true of the mayoral campaign. Early on, councilman and mayoral candidate Joe Buscaino used a tent village at Venice Beach as a backdrop for a call to crack down on camping. Critics screamed about the criminalization of homelessness, but only Bonin and Councilwoman Nithya Raman voted last summer against an initiative to outlaw camping near parks, libraries, schools and other locations.

U.S. Rep. Karen Bass, considered a front-runner in the race for mayor, is a solid liberal. But even she drew a line on encampments when she announced her run.

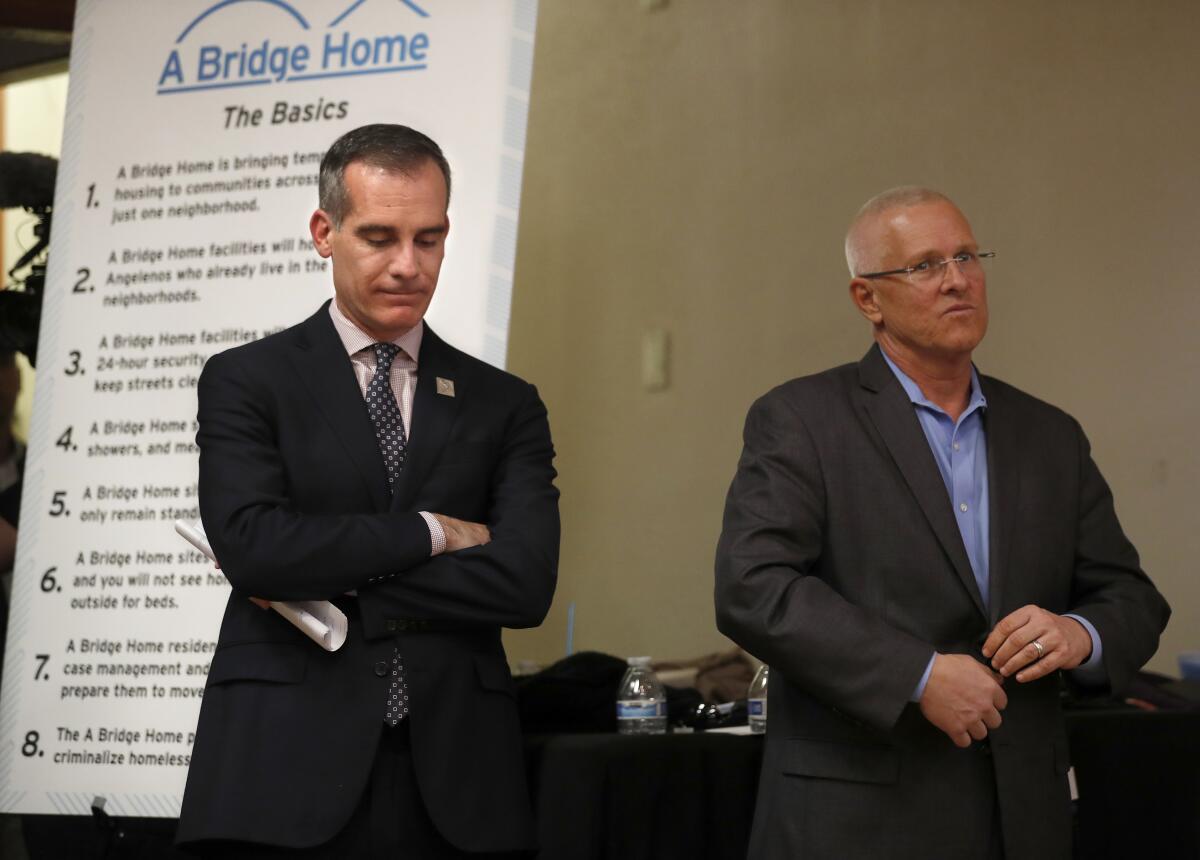

For four hours, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti took the heat from a crowd in Venice.

“The bottom line is people will not be allowed to live on the streets,” Bass said. “There are just some things that you don’t do outside, and sleeping is one of them.”

The eternal question, of course, is how to deliver on such a promise.

When I toured Venice the other day, the beach scene was in stark contrast to what it was like when tents lined a long stretch of the boardwalk. Bonin partnered with the nonprofit St. Joseph Center last year to steer more than 200 people into various forms of housing, by his count.

But as my colleague Doug Smith pointed out in a story, not everyone stayed housed. And as candidates for Bonin’s seat told me, some of the scattered beach dwellers simply pitched tents elsewhere.

“One of the things that was observed around the time of the cleanup was a corresponding uptick” in the number of tents in parks and residential neighborhoods, Park said. As for the hotly contested bridge housing facility, Park said, the immediate effect was more homelessness-related problems on the street rather than fewer, which served to ratchet up the calls for Bonin’s ouster.

Some of those problems have been addressed since those early days, but just a few blocks away, in an area just south of Rose Avenue, tents line streets with posted warnings that tents can’t be erected between

6 a.m. and 9 p.m. and that “no blocking of the sidewalk” is allowed.

“I don’t think it’s inappropriate for the city or the public to expect rules to apply,” said candidate Good, adding that encampments aren’t good for the unhoused or the housed.

So what would Bonin’s would-be successors do about it?

In addition to Park (a lawyer) and Good (former chief of legislative and external affairs for Garcetti), I spoke to Council District 11 candidates Allison Holdorff Polhill (a lawyer and former educator) and James Murez (Venice Farmers Market manager). All four said they support the anti-camping ordinance and would enforce it.

“I don’t think it goes far enough,” said Murez, who added that large available swaths of land near the airport and elsewhere should be established as legal, managed campsites until people can be directed to more permanent housing. He said he tried to persuade Bonin to consider such ideas but got nowhere.

“My belief is that Mike’s philosophy about let them stay on the sidewalks until we have housing for them is fundamentally broken” and inhumane, Murez said.

For years, critics have said that temporary shelter housing is a tool used to sweep people off the streets without addressing long-term needs. But the candidates said nothing is as bad, for the unhoused or the housed, as leaving people outdoors where health and safety issues fester.

“We need temporary shelter, 100%,” said Polhill, who cited multiple studies identifying available buildings and property that could be put to use. Polhill told me she decided to run for council after dozens of hypodermic needles were found on the perimeter of a school in Venice, and she wants more of a focus on homelessness prevention and mental health housing and services.

Two candidates told me they thought Good’s attachment to the Garcetti administration would be a liability, given the lack of trust in City Hall. Good, who was at that 2018 meeting where anger at Garcetti and Bonin boiled over, said more people have been housed citywide in the last several years than ever before, and that he had a hand in the successes.

In a swipe at Bonin, he said District 11 needs a leader who engages everyone rather than bulling ahead without building consensus.

For the tourists, it may be the Ocean Front Walk of old: quirky shops, beachfront restaurants, sculpted bodies and assorted sketchy characters. But for residents, last summer’s effort to clear nearly 200 tents from the promenade didn’t do the job.

Whoever succeeds Bonin is going to find that the fractured, multi-agency homeless services bureaucracy is an incorrigible beast. Then there’s the housing crisis, abject poverty, mental health service failures and other forces beyond direct control of a council member. In many instances, helping someone can be complicated.

A few blocks from the beach, I met a woman named Gwen who told me she had been in federally subsidized housing, a shelter and a Project Roomkey hotel. But for all that, here she was, living in a tent and getting around with the aid of a cane and a walker. She said she’d rather be on the street because indoors she had been assaulted and robbed, and she feared getting COVID-19 in a shelter or hotel.

While I spoke to her, a young, visibly distressed woman sat beside her tent maybe 25 feet away from us. She then rose, dropped her pants and relieved herself on the sidewalk.

It was a snapshot of the catastrophe.

A sad young woman, in need of help she may or may not get, anchored in a besieged beachside neighborhood that is a depository of unmet challenges.

We’ll find out soon enough if any of the candidates is up to meeting them.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.