Train robberies — great or pedestrian — are nothing new in California

- Share via

They really did holler, “Stick ‘em up!” They really did tie bandanas around their faces, and blow open railway car doors and safes with dynamite (although not always with the intended results). They really did derail trains to get at the loot.

Train robbery lore has become so outsized in our mythic history — Jesse James and Butch Cassidy and the Dalton gang — that what’s happening now in Los Angeles, with Union Pacific being ransacked of consumer cargo, is startlingly low-tech, haphazard thievery in an age when you can steal millions with a mouse click. The mauled scatterings of boxes and packages along the train tracks look like the crime scene from a Christmas Eve Santa sleigh-jacking.

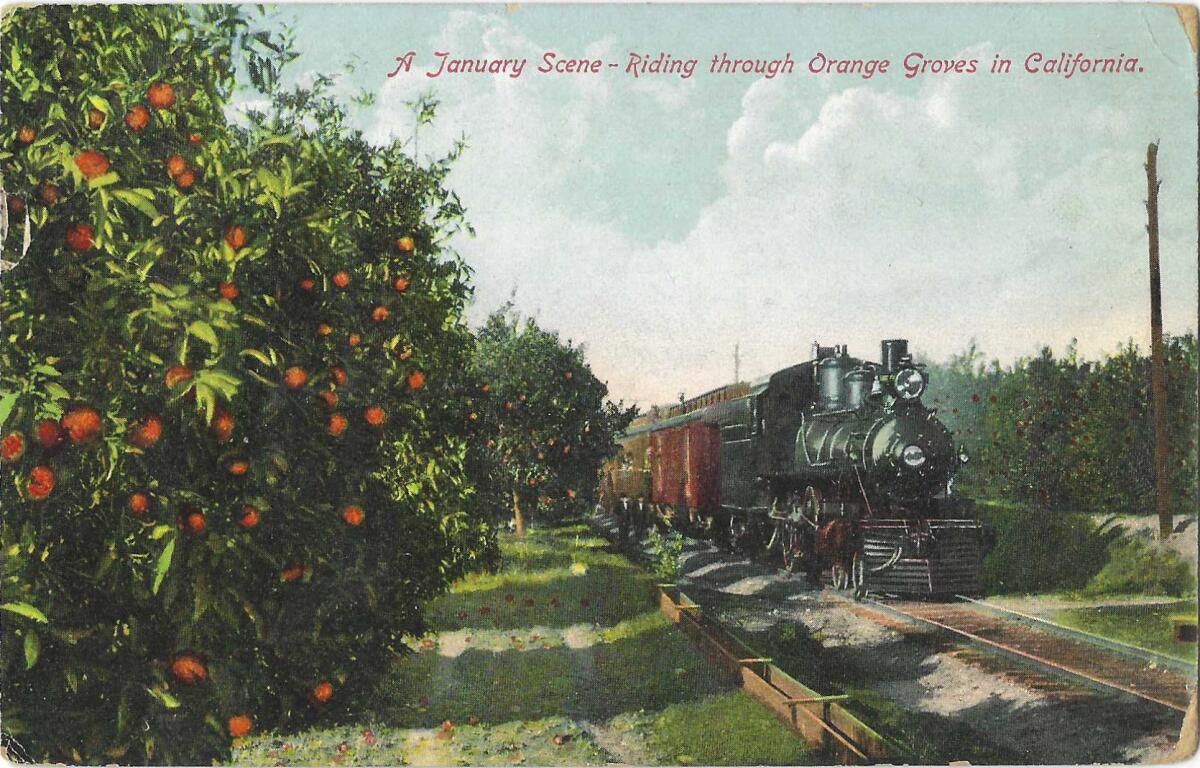

New crimes usually ride hard on the heels of new technology. As miners began hauling gold and silver out of the hills and streams of California and Nevada, it was first the stagecoaches ferrying the goods to and fro that got held up and plundered for the loot.

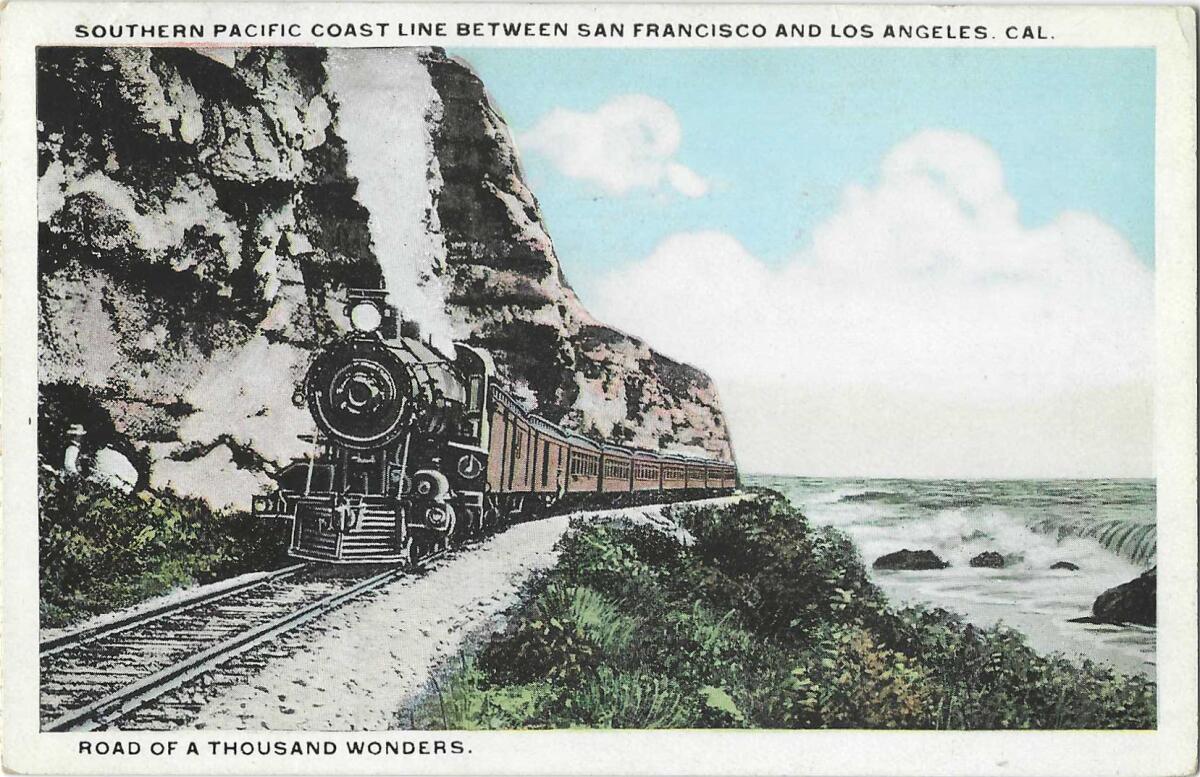

But trains, those huge cars carrying hundreds of times more weight than horseflesh can, beckoned felons from the highways to the railroad tracks.

It looks like the first such train robbery in California was in 1881. A train-wrecking crew, led by a man who hadn’t made good as a gold miner, decided to intercept other men’s gold at a less labor-intensive stage of things.

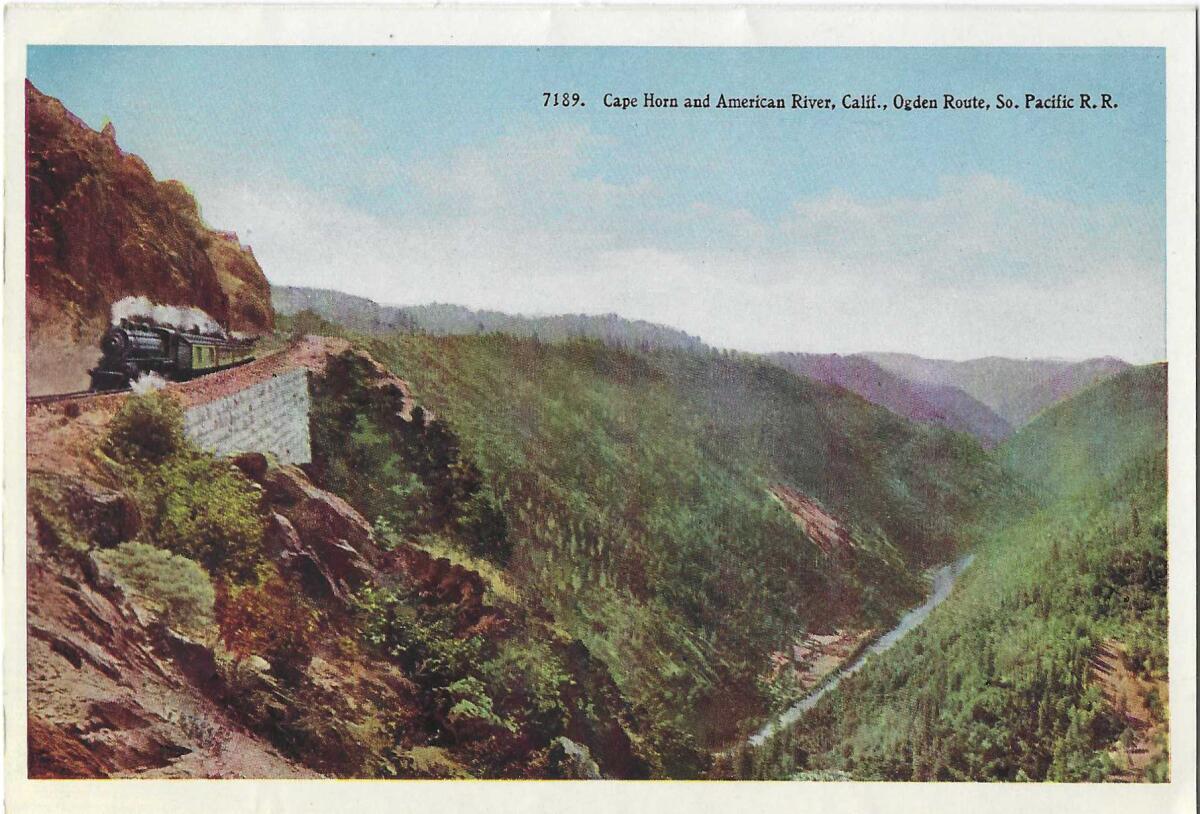

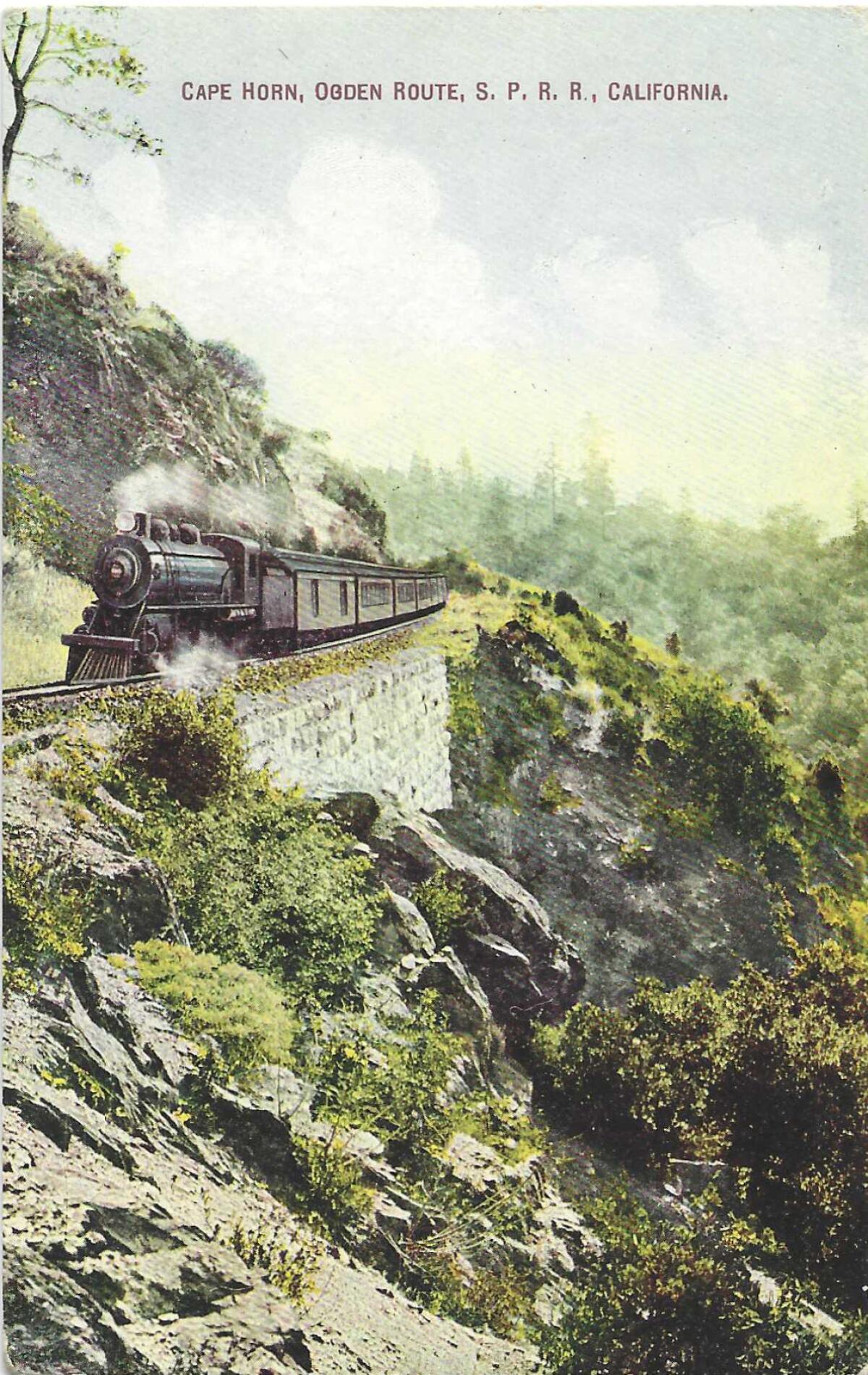

It happened east of Colfax, at the edge of the Sierra, near the dizzying mountainside Cape Horn section of railroad. The gang deliberately damaged the rails, and when the locomotive and maybe other cars toppled over, they moved in with guns. But the men guarding the Wells Fargo car and the mail car stood their ground. The robbers went away empty-handed, and were tracked down and tried.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

The best part of this saga, so says the book “Great Train Robberies of the Old West,” is that it emerged during the trial that Wells, Fargo & Co. — which had lost not a farthing in the robbery, and agitated for an expensive, relentless prosecution — hadn’t paid local taxes in several years, a rumored sum of $90,000. That little nugget of information ticked off taxpaying locals something fierce, given that they were footing the bill for the trial of bungling robbers. They wound up with two convictions, two acquittals, and some hard feelings against Wells Fargo. Shades of modern billionaires stiffing the public coffers on their profits.

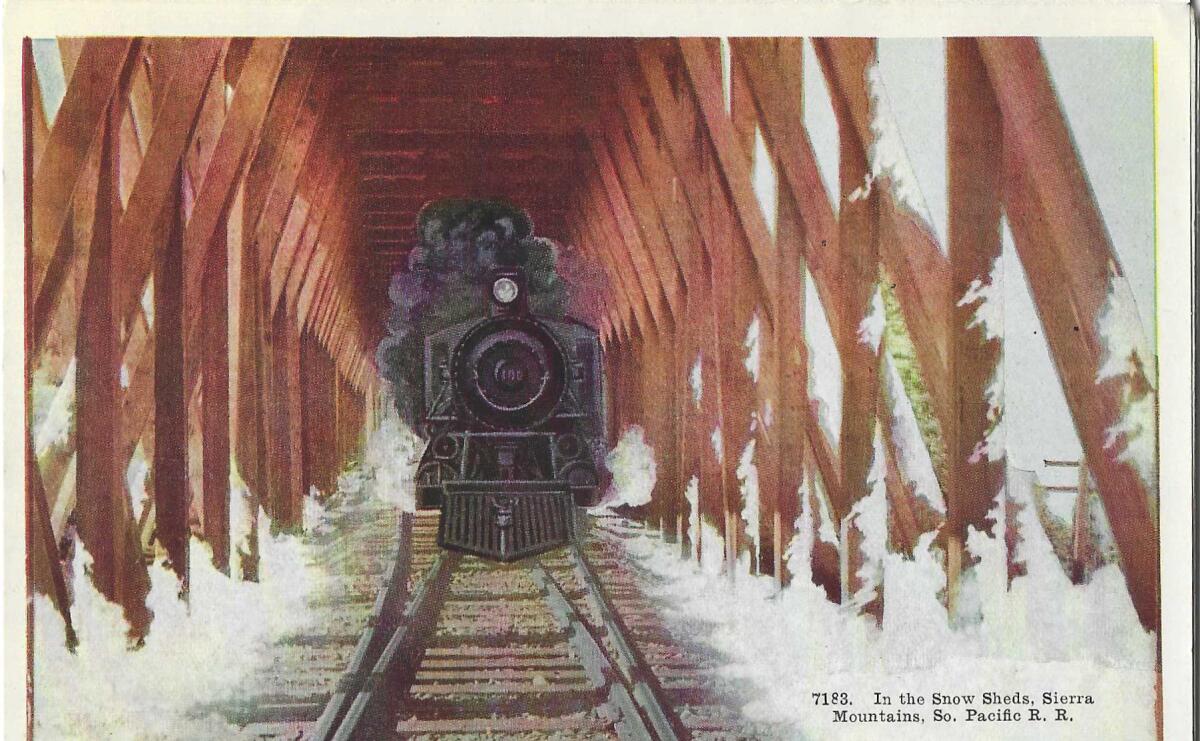

The Central Valley was plagued by a passel of train robberies in the last decade or so of the 19th century. These were serious holdups, with gunplay, corpses sieved with bullets, and explosives to blow a path to the cache of goods, which wasn’t always as rich as the robbers had expected.

For a time, two of the men, Chris Evans and an aggrieved former Southern Pacific railway brakeman named John Sontag, dodged the law and acquired a patina of folk heroics, even after an enormous manhunt and shootout left Sontag and two lawmen dead. The Times scolded that “seeing that such a man [Evans] is regarded by many as a hero, it cannot be wondered at that many young men should prefer to imitate him rather than to seek to do honest work for modest pay.”

Evans, who lost an eye and an arm in the shootout, escaped from prison and was tracked to his Visalia home. Realizing that the game was up, he sent out his little boy to the sheriff with a note: “Come to my house without arms and you will not be harmed. I want to talk to you.” He and his men duly surrendered.

Back in 1893, even as the Evans-Sontag gang were on the lam for dynamiting a Southern Pacific train and making off with thousands in coins, Evans’ wife and his teenage daughter, Eva, were appearing onstage in “Evans and Sontag, or, the Visalia Bandits,” a potboiler about the train robbery.

A San Francisco Examiner reporter asked Eva whether she had stage fright at the prospect of her performance. “Why, it can’t be anything compared to going through the scenes in reality.”

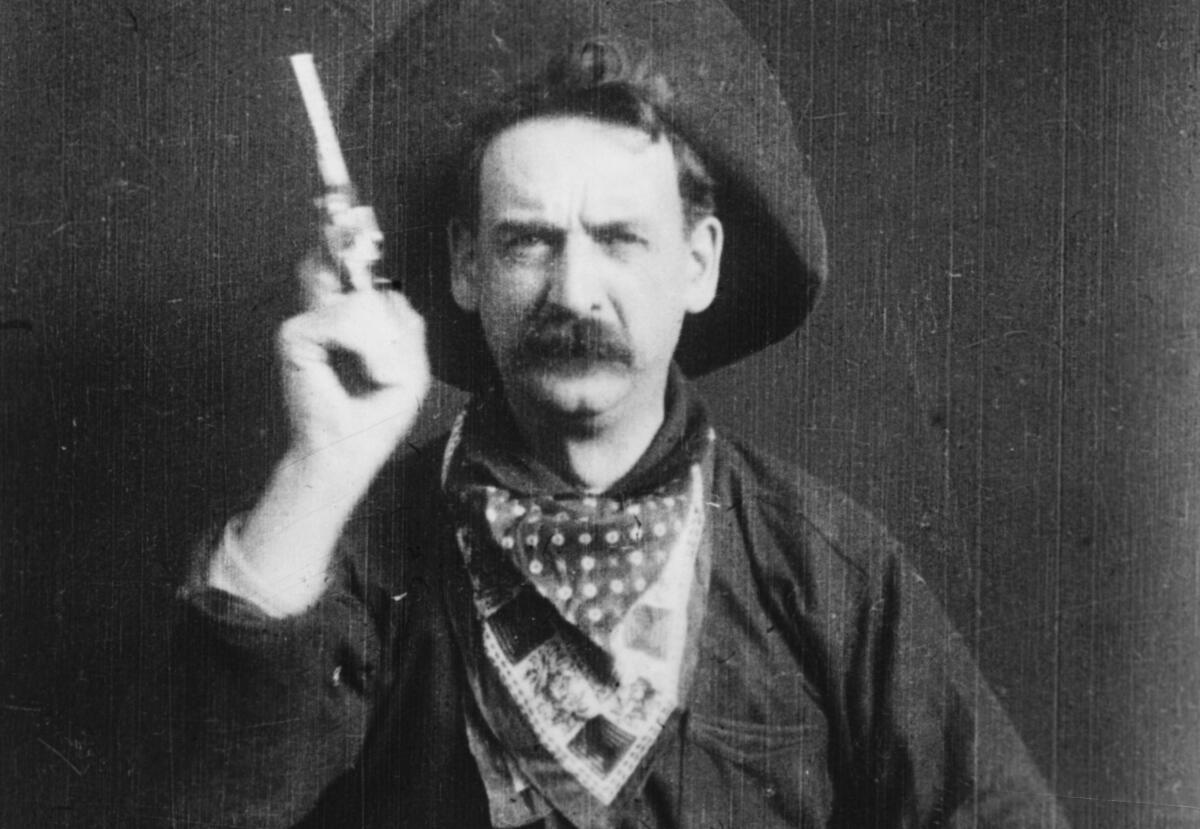

By the early 20th century, the train robbery MO was on its way to film genre status. Cashing in on the headlines, a 12-minute movie called “The Great Train Robbery,” the granddaddy of all train heist movies, ended spectacularly, with an actor facing the camera and shooting his gun four, five, six times at the audience. It was a sensation.

Ten years later in 1913, when John Sontag’s brother George got out, he announced his intention to make and star in a movie about the gang’s deadly shootout with the law. Nothing shows he ever did, but it made for a splashy exit from the slammer.

It should be pointed out here that Southern Pacific was not in good odor with much of the Central Valley’s residents. The railroad had sharp elbows and sharp business practices and had generated land speculation, profit and ruin, depending on where it laid its tracks or chose not to.

All of this had been brought to a bloody boil in 1880 in a murderous incident at Mussel Slough, near Hanford. After vastly complicated, sometimes murky years of railroad land claims and settling and squatting and eviction battles and challenges to the railroad’s power, the Mussel Slough shootout killed seven men, five of them from the settlers’ group.

Some of the surviving settlers were convicted of federal charges and spent months in prison. They were welcomed home as conquering heroes. “Remember Mussel Slough!” was on the lips of farmers up and down the Central Valley, and the event took on mythic status in fiction, most famously the Frank Norris novel “The Octopus,” which in prose and in the public’s mind cemented Southern Pacific as the father of all villainy.

Chris Evans’ wife’s family had supposedly lost Mussel Slough property claims to Southern Pacific, which could explain a great deal, including the folk acclaim for the gang.

Evans swore to the last that he had never committed the robberies, and was paroled in 1911 by Gov. Hiram Johnson. Talk about closing the circle: Johnson was the progressive Republican who promoted California reforms such as the referendum, initiative and recall, measures that gave voters an end-run around the death grip that the railroads held on the state’s politicians.

From that Greek-tragedy tale, let’s move to a comic opera: the notorious Dalton gang. Whatever their win-loss record elsewhere, their one California foray into bank robbery ended in humiliation — theirs — and death — not theirs.

In February 1891, near the town now called Earlimart, a trio of masked Daltons on horseback stopped an SP train. They shot the engineer, and one brother fired in the air to keep passengers at bay while the others tried to force the guard inside the cash car to open the door. The guard instead started shooting through a peephole until the Daltons gave it up and rode off empty-handed.

Much closer to L.A., a pair pulled off two train robberies — one of them in Sun Valley, which then bore the name of Roscoe, and the best (and unlikeliest) story is that it got the name because “Roscoe” was slang for a gun.

Too bad for local legend, the place was already called “Roscoe” in newspaper stories. And the stories poured forth. In 1893 and again in 1894, a convicted horse thief named W.H. “Kid” Thompson and a Big Tujunga man named Alvarado Johnson, who had lost his ranch to SP’s high produce shipping prices, stopped two different trains, derailing one of them, and held them up.

The first time got them $150. The second time netted $1,500 in gold and silver coins — and eventual life sentences because the crash killed a train fireman and a tramp.

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

Thompson managed to get a retrial. Just before it began, he sent a high-flown letter to The Times, which had once pontificated that “the hanging of a few of the desperados engaged in this business would have a salutary effect.” Thompson protested that the newspapers “have endeavored to make it unpleasant for me by applying to me all sorts of epithets which stigmatize me as a red-handed murderer.”

When it comes to making the kind of mess that now litters the side of the tracks in the UP thieveries, look back to early December 1902, when Angelenos were shipping Christmas gifts to the East Coast by train, and the very prosperous among them were sending jewels and silver and securities.

How the case against Charles Ray Spaulding ended, The Times doesn’t say, but L.A. lawmen say Spaulding was a driver of a Wells Fargo wagon as laden with riches as a pasha’s trove, heading to the Santa Fe station for the 8 p.m. train when the allure must have overcome him.

He stopped his wagon in Eastlake Park and began flailing through the boxes like a kid on Christmas morning, tossing wrappers hither and thither, ripping open envelopes of money and valuable securities, and shredding the driver’s log book of shipping information. The stuff that was too heavy to carry off — large silver pieces and fancy luggage — was left behind when Spaulding vanished.

For almost 10 years, Spaulding was missing. When he was found, he was in Sing Sing prison in New York. Back in L.A. for trial, he tried to engineer an escape by sawing through his cell’s window bars and hiding the cuts with blackened soap.

That was so old school. Once again, as monetary technology changed, so did crime. In 1904, after robbers hurled a safe off the express car of an SP train north of San Luis Obispo, a Wells Fargo man surnamed Campbell doubted there was much inside it anyway.

“There was a time when almost every limited train traversing this part of the country carried in its express car a good sized fortune in cash … now it is different. There are other means of transporting it, and one of the favorite methods is simply in transfer credits to the banks.”

Campbell remarked on the “fewer and fewer express robberies each year. When criminals realize they will only get a few hundred dollars … they will hesitate before taking the chances which repose in a [railroad] messenger’s sawed-off shotgun or a stiff sentence from the court.”

Dwindle they did. “John Bostick” didn’t go for a safe when he held up an SP train near El Monte in 1913; he went for the passengers’ riches, and he killed an undercover SP agent who tried to stop Bostick from stealing a passenger’s engagement ring.

Bostick had pulled off a similar crime near Oakland a month earlier, and when he was arrested, he was wearing a sapphire from that heist, and carrying a pawn ticket for the ring. His real name was Ralph Fariss, and he’d been a bad lot since he was a teenager sent to reform school.

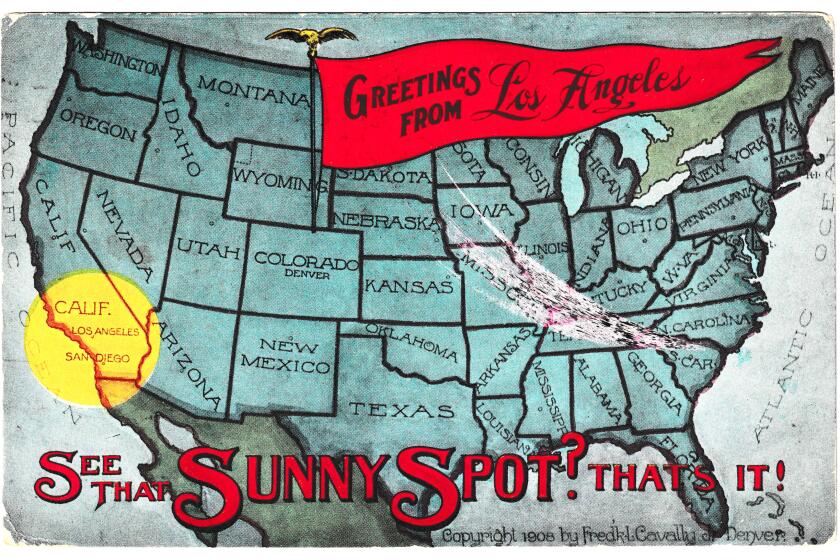

Sunny and mild L.A. winters have long been used to sell our town to frigid Midwesterners and Easterners, attracting the sick, the farmers and the moviemakers.

His ailing parents recognized his picture in the paper and set out on the trek to visit their son in San Quentin before he was hanged. It was because of them, he said, that he’d used a friend’s name and not his own. “It’ll be better for my father and mother if I swing as Bostick and not as Fariss.” His father, perhaps not incidentally, had been an SP conductor and lost a leg in an accident.

Mere weeks after Bostick’s execution, “an Englishman with an education,” named J.W. Burke, confessed to sticking up a mail car near L.A.’s principal train station. By then, life was imitating the movies imitating life. Burke’s partner, described by The Times as a “cocaine fiend” named Jean La Banta, and an old hand at train robberies, told the agent in the mail car, “Stick ‘em up, you --- --- ---.” The next day, Burke got his share of the haul: a cool $30.

Such was the pressure brought to bear for a law to match the offense that in 1905, it became a death-penalty offense to kill someone by derailing a train. It was that law that was under consideration in Los Angeles a hundred years later, after a suicidal man parked his gas-drenched Jeep on a Metrolink track in Glendale, and killed eleven people in the derailment. He was convicted of 11 counts of murder, but not of train-wrecking.

And now for my confession: I come from a train-robbing family.

During the Depression, a great-uncle who worked for the railroad would alert my grandfather when a coal train was coming through town. My grandfather’s two older boys, my uncles, then probably 10 and 11 years old — my father was still far too young for this crime-family stuff — would hustle a mile or so out of town, climb aboard the rolling coal car, throw off as many hunks of coal as they could, then hop off the train, and go back later with a wheelbarrow to collect the coal they’d tossed. It kept them warm through the winter. Don’t worry, officers — I’ll go quietly.

Union Pacific has reported an alarming 160% increase since December 2020 in thefts along railroad tracks in L.A. County.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.