COVID-19 deaths rise in L.A. County, but officials blame Delta more than Omicron

- Share via

Los Angeles County has recently noted an increase in coronavirus deaths, but officials think they are mainly tied to the Delta variant, rather than the prolific Omicron strain that has fueled record-high infections in the county and across the state.

Over the last week, the county has averaged 24 reported COVID-19 deaths a day, up from about 14 a month ago. L.A. reported 39 COVID-19 deaths Wednesday and 45 on Thursday — the latter of which is the highest daily fatality figure recorded over the autumn and winter.

Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Thursday she believes there are still people infected with the previously dominant Delta variant who have been dying in L.A. County’s hospitals.

“Many people are sick for quite a while and many are hospitalized for quite a while before they pass away, so it is likely that most of the deaths we are seeing are still related to Delta, although not entirely,” Ferrer said.

Nationwide teachers, parents and students have had to deal with the Omicron surge.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, expressed the same sentiment earlier this week.

“Given the sheer number of cases, we may see deaths from Omicron. But I suspect the deaths that we’re seeing now are still from Delta,” she said Wednesday.

She added: “We will need to follow those deaths over the next couple of weeks to see the impact of Omicron on mortality.”

Statewide, an average of 108 Californians have died from COVID-19 per day over the last week, according to data compiled by The Times. That’s more than double the level from two weeks ago.

Hospital situation

There is growing evidence that Omicron spreads much more quickly than its Delta cousin but causes less severe illness for many.

But the unprecedented rise in overall cases is still a challenge.

Los Angeles County’s hospitals are straining to provide medical care, hobbled by staffing shortages far worse than last winter’s coronavirus surge.

Many healthcare workers, burned out by the pandemic, have quit, and many who remain have tested positive for the virus and are at home isolating. And healthcare facilities are busier this year because there’s more demand for non-COVID-19 care.

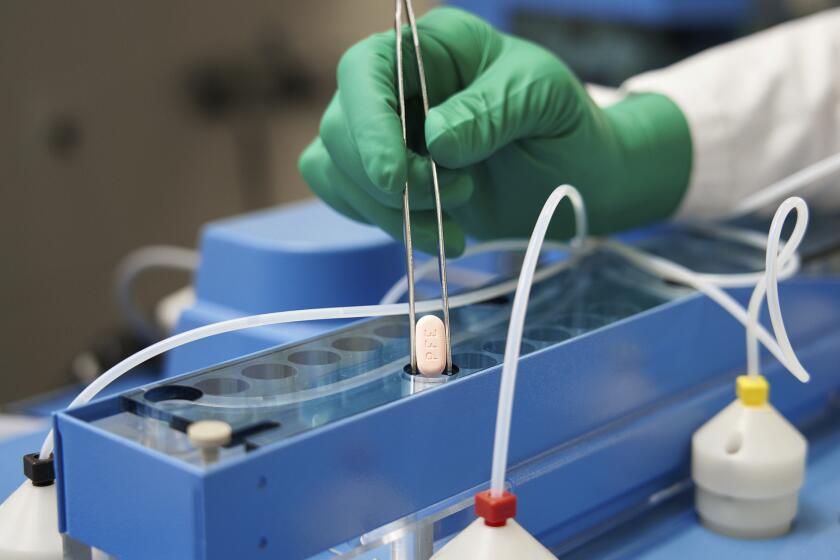

Two brand-new COVID-19 pills that were supposed to be an important weapon against the pandemic in the U.S. are in short supply.

Total hospitalizations: The number of people hospitalized for all reasons is also increasing and has reached 15,000 in L.A. County. That’s close to the peak of 16,500 from last winter’s surge, Ferrer said.

ICUs: COVID-19 patients are also comprising an increasing share of L.A. County’s intensive care unit patients, nearly 25%. That figure was 10% around Christmas. During the summer Delta surge, that number peaked at 20%, and last winter, it maxed out at 70%.

Ventilators: There’s also an increase in the percentage of patients on ventilators who have COVID-19. About 20% of ventilated patients now have COVID-19; that figure was 10% last month. The latest number is the same as the summer surge, and is one-third last winter’s peak.

“This means that Omicron is causing not just an increase in the overall census at hospitals, but it’s also driving increases in the proportion of ICU and ventilated patients,” Ferrer said. “And while, thankfully, this is not at levels that we saw during last winter surge, these numbers do serve as a stark reminder that, for a growing number of people, Omicron is causing severe illness.”

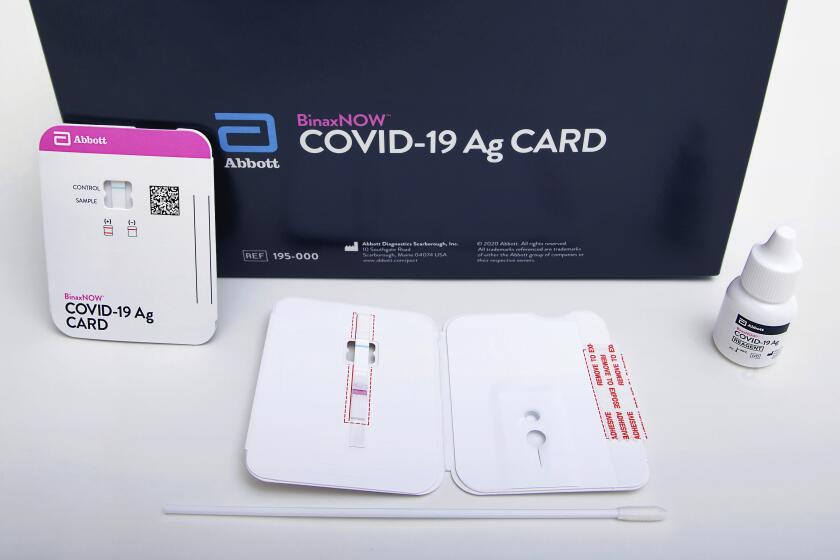

As the Biden administration tries to cut the cost of home COVID tests, health insurers will begin paying for them. But that won’t increase the supply.

Understanding Omicron

Omicron is the dominant coronavirus strain in the U.S., accounting for an estimated 98% of new cases nationwide, according to the CDC.

New data from Southern California are providing further evidence that the Omicron variant is causing less severe illness than Delta, the culprit behind last summer’s wave.

A preliminary study based on medical records from nearly 70,000 Kaiser Permanente Southern California patients “noted substantially reduced risk of severe clinical outcomes in patients who are infected with the Omicron variant compared with Delta,” Walensky said.

The study — which included more than 52,000 Omicron cases and nearly 17,000 Delta cases within the Kaiser system from Nov. 30 to Jan. 1 — found that, compared with patients infected with Delta, those who had Omicron were 53% less likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, 74% less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit, and 91% less likely to die of the disease.

Among patients who were hospitalized, the median length of stay was 1.5 days for patients infected with Omicron and five days for those who had Delta.

California’s healthcare system is expected to face continued stress in coming weeks as the Omicron variant spawns new waves of coronavirus infection.

Omicron’s dangers

Even though an Omicron infection is less likely to result in hospitalization, California is still estimating that about 4.5% of residents will require a hospital stay with this strain of the virus. And, officials warn, it’s not clear how survivors will fare with long COVID, which can result in illness that lasts for months or longer, nor how likely child survivors of Omicron will be to face multisystem inflammatory syndrome, or MIS-C, a rare but serious complication that can be deadly.

“Anyone who tells you that, for certain, you can assure someone they won’t have long-term [consequences] from having an infection; anyone who tells you, for sure, they know that this variant will give you immunity that will last forever and so, therefore, you should go out and get infected — they don’t know,” said Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, chair of the UC San Francisco department of epidemiology and biostatistics. “Because the best virologists, the best epidemiologists, the best physicians don’t know and disagree on these various topics.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.