- Share via

The nurse helped tie our isolation gowns before we stepped into room 416.

My sister Crystal Vargas and I were in the COVID-19 intensive care unit at Huntington Hospital. Staff watched a handful of patients on computer monitors, including our grandmother María Díaz.

Inside the room came the steady whoosh of air getting pushed into her lungs by an oxygen mask that obscured her face. The numbers on her hospital monitor signaled that her blood pressure had plunged to 79/46 mmHG.

We placed our purple, gloved hands over hers — the hands that fed us, bathed us and brushed our hair. They were cold despite the pile of blankets that enveloped her thin frame. Her blue eyes were closed to the world.

Our grandma had tested positive for COVID-19 and been admitted to the Pasadena hospital the night before, Dec. 13. Even with the help of the BiPap machine, a type of ventilator, her oxygen stats were trending down. She had COVID pneumonia and was “sick all over her body,” the nurse said.

We were there to say goodbye.

For many, COVID-19 is what forced them to stay home and wear a mask to keep others safe — the virus existing largely in the abstract. For me, it’s what came to define these last two years, personally and professionally.

It’s what tore through my family, infecting nearly 30 relatives here and in Mexico, just on my mom’s side. It’s what led me to drive my cousins to say goodbye to their father, who was on a ventilator. It’s what was now stealing the heart of our family.

It’s also what divided my family.

“Other families have experienced equal disaster with COVID in terms of other people that they know having become infected,” said Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer. “I don’t know anyone who wasn’t affected by last winter’s surge.”

Frustration grows among doctors and nurses at a Southern California ICU where unvaccinated COVID patients are struggling for their lives.

This year, I thought hope had come in the form of the vaccine. But I had family members who didn’t trust it, others with excuses for why they didn’t need it.

Meanwhile, they kept working essential jobs. Like many whose extended families fell to the virus, their work could not be done from the safety of their homes. So the risk never faded.

My grandma was not vaccinated — not of her own will — and I fear it is a decision that will haunt my family and evoke anger for years.

::

María Luisa Díaz was born Oct. 5, 1925, in Guadalajara.

An only child, she was raised by her mom and her grandmother, who was nicknamed güera for her pale skin and blue eyes. My grandma said inheriting those eyes, which changed from blue to green, made her a catch.

She told Crystal stories about Pablo, the “hot guy” driving around in a motorcycle. He pursued her, and she ignored him, until they finally married. She wouldn’t find out until later that he had a second family across town.

They had seven children together — the youngest died of pneumonia — before she left for California, tired of her husband’s cheating. Stories vary on who got to the U.S. first. But eventually, my grandma and five of her children were settled there. Her oldest son, Beto, chose to stay in Mexico.

My grandma couldn’t work as a nurse in the U.S., so instead she worked in a factory sewing costales, burlap sacks. Eventually, she saved enough money to buy a house in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, before it gentrified.

When she paid off the house and got the deed, she told Crystal, “This is what it feels like to be an American.” She became a citizen a few years later, keeping the miniature U.S. flag as a testament to that day.

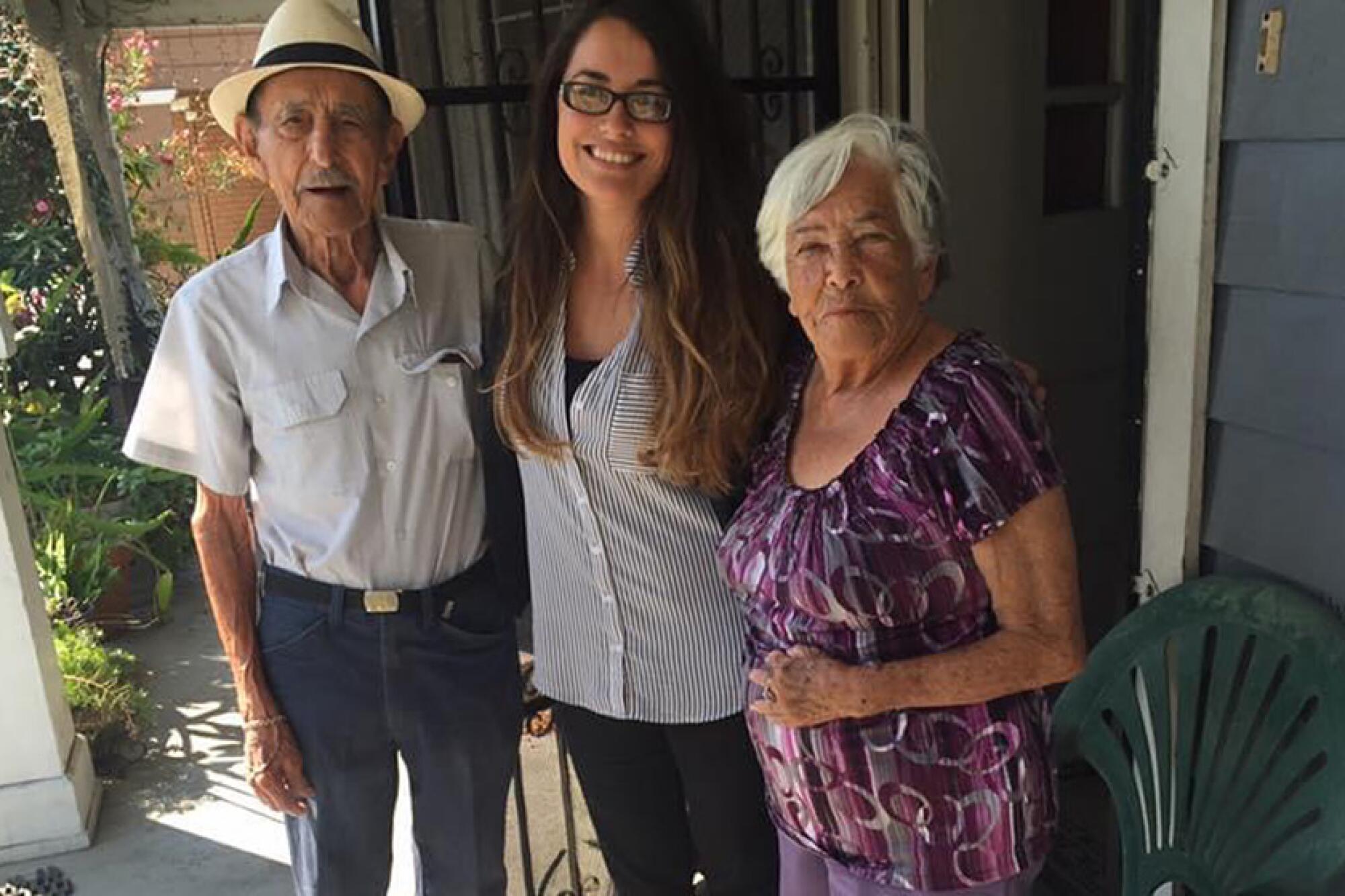

My grandma’s house sits around the corner from my uncle’s mechanic shop and down the street from my tía’s house. It’s where my two oldest sisters grew up and where another sister and I lived for a while, too. Her garden in the front yard was her pride and joy. (I recently joked with my sister that the plants got more water than we did during bath time.)

Some of my favorite memories are of settling down on my grandma’s bed at the end of the night to watch telenovelas (I still remember “El diario de Daniela”) and her dressing me up in the colors of the Mexican flag for a celebration at Latona Elementary School. She was the one who would buy me a pink concha at Superior if I was good and who scolded me when I stayed after school for snack time instead of coming straight home. She bought me a pocket-size dictionary that I treasured.

Her house became the landing spot for so many of us, a refuge when we needed to get back on our feet or were essentially orphans. The photos of six of her kids, 30 grandkids and dozens of great-grandkids decorate the mantle in her living room.

“That house was like the hub,” Crystal said. “It was never a question to ask if someone could stay. You didn’t have to ask Grandma.”

It’s where I returned after graduating from college in 2014 and starting at the Los Angeles Times. I slept in the back room, and after work, I’d sit on her bed and watch telenovelas like I did as a child.

By then, her memory had been fading for years. Every day, I would reintroduce myself as “la hija de Lupe,” the daughter of Lupe (short for Guadalupe). On the good days, she would tell me about being a nurse and her life back in Mexico. On the bad days, she’d try to kick me out of the house because she thought I’d broken in.

I choose to remember the good.

Like the time I was upset and she told me “Todo pasa, mija” — all things pass. And the night we got to celebrate Las Posadas, a procession in Highland Park depicting the biblical story of Joseph and Mary’s search for shelter at the time of Christ’s birth. I still have the photo of her staring in wonder at a sparkler in her hand as we knocked on doors.

Even as her memory slipped, we carried her story — our family story — with us. For us, it all boiled down to one thing: Our grandma was a chingona. Badass.

Which is why, when the pandemic hit, we knew we had to protect her.

::

The virus came for my family members one by one.

My tío Beto died first, while I was reporting as part of the politics team in Florida in October 2020. My family said he had dengue, but his wife tested positive for COVID-19 within days. He was never tested. The same day I learned the news, I interviewed people who told me that the virus was nothing more than a flu. My eyes still hurt from crying in my hotel room over the loss of my uncle.

The same month, my cousin told me that our grandpa had tested positive for the virus. Some of my family said it wasn’t COVID but long-standing health issues that eventually led to his death, resulting in heated arguments.

After that, we fell like dominoes.

A cousin got it through her husband, who worked in a warehouse. Later it was my cousin’s sons, who worked at Costco. I spent Christmas reporting in the ICU around the same time that an aunt on my dad’s side was on a ventilator.

The next month, my mom’s brother was placed on a ventilator. On Jan. 27, I drove my cousins to the hospital to say goodbye to him, because they feared the worst. I was both Uber driver and therapist on that tense drive.

We were all relieved when he turned the corner and improved enough to be released, although he’s now a COVID long-hauler.

Our experience was a lived reality for families across the country, especially for Latinos who faced a disproportionate impact.

In an interview, my colleague and close friend Maria L. La Ganga spoke to Ferrer about the devastation the virus has wreaked on my family.

“For some families, the magnitude of COVID has been utter devastation,” Ferrer said. “Unfortunately, depending on your social network, depending on your opportunities for telework, depending on how you feel and your confidence in the medical system and advice from public officials like myself, it really said a lot about how people were able to get protected and how many people were not able to be protected.”

We thought that the danger had passed when the vaccines came around. I worked hard to convince family members to get vaccinated and was able to get at least 10 of them the shot. But I couldn’t convince everyone.

I had family members who cited the possibility of having an allergic reaction as a reason not to get it. (Such occurrences are rare, experts say.) Others blamed a doctor who allegedly said my grandma was too old and frail to get vaccinated. My grandma’s care wasn’t in my hands, but it’s hard not to feel some guilt.

When a handful of us gathered at my grandma’s house on Thanksgiving weekend to eat menudo, only two people were unvaccinated, including my grandma.

In the following weeks, my aunt, uncles and parents would all test positive. I was one of the only ones who tested negative.

Eventually, what we’d all been dreading became a reality. My grandma was taken to urgent care because she was struggling to breathe. She tested positive, too.

::

On Dec. 13, Huntington Hospital had 22 COVID patients, including my grandma.

She was one of eight patients being cared for in the COVID ICU. Five days later, that’d jump to 13. Dr. Kimberly Shriner, Huntington Hospital’s medical director of infection prevention and control, worried about what the rest of the winter would bring.

“When you see someone with this disease, and you watch somebody die from this disease, it’s really awful, and it’s very traumatic,” Shriner said. “Most people that go into healthcare do it because they want to help people, but it is really pushing them to the limits.”

On Dec. 14, Crystal and I brought coffees and a box of conchas, a “thank you” to the nurses who had fielded phone calls from my family all day.

We sobbed as soon as we stepped into room 416. My grandma had never looked so small. Crystal and I had 30 minutes to video call our family in the U.S. and in Mexico so they could say goodbye.

Generations that all traced back to her — children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren — told her repeatedly how much they loved her. My cousin said, “Ya te puedes ir a dormir, Grandma.” “Now you can go to sleep.”

Occasionally, I felt my grandma squeeze my hand as we cried. Crystal pushed her hair back behind her ear and touched her lobe — she had been the one tasked with putting on my grandma’s earrings.

My niece Maria Hernandez, who was raised by our grandmother, broke our hearts. She’s pregnant and due in January.

“Me duele que no vas a poder ver a mi hija.” “It hurts that you’re not going to be able to meet my daughter.”

Her son thanked her for everything she’d done for her family.

“Te ofrezco mi amor eterno.” I offer you my eternal love.

“Thank you for being my mom,” Crystal told her in Spanish. “I love you so much.” She told my grandma that she was the strongest woman in the world. A “chingona.”

“Thank you for being so strong and for being the example for the rest of us,” I said. “We love you so much.”

In the minutes remaining, the extra ones allotted to us by my grandma’s kind nurse, Crystal pulled up the song “Amor Eterno,” fittingly sung by Rocío Dúrcal — a María too, like my grandma. The lyrics, written by Juan Gabriel, were inspired by the loss of his mother.

As the last few hours of her life slipped away, a single tear formed beneath my grandma’s eye while the lyrics played:

Como quisiera que tú vivieras

Que tus ojitos jamás se hubieran

Cerrado nunca y estar mirándolos

Amor eterno e inolvidable

How I wish that you had lived

That your eyes had never closed and to be looking at them

Eternal and unforgettable love.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.