Sixty-foot waves exploded off the Pacific Coast during October’s bomb cyclone

- Share via

The bomb cyclone and atmospheric river that pummeled Northern California in late October produced exceptionally heavy rain and high winds. But it also battered the California coast with some epic ocean waves. During the storm, peak individual wave heights of as much as 60 feet were measured from Washington to California, according to researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

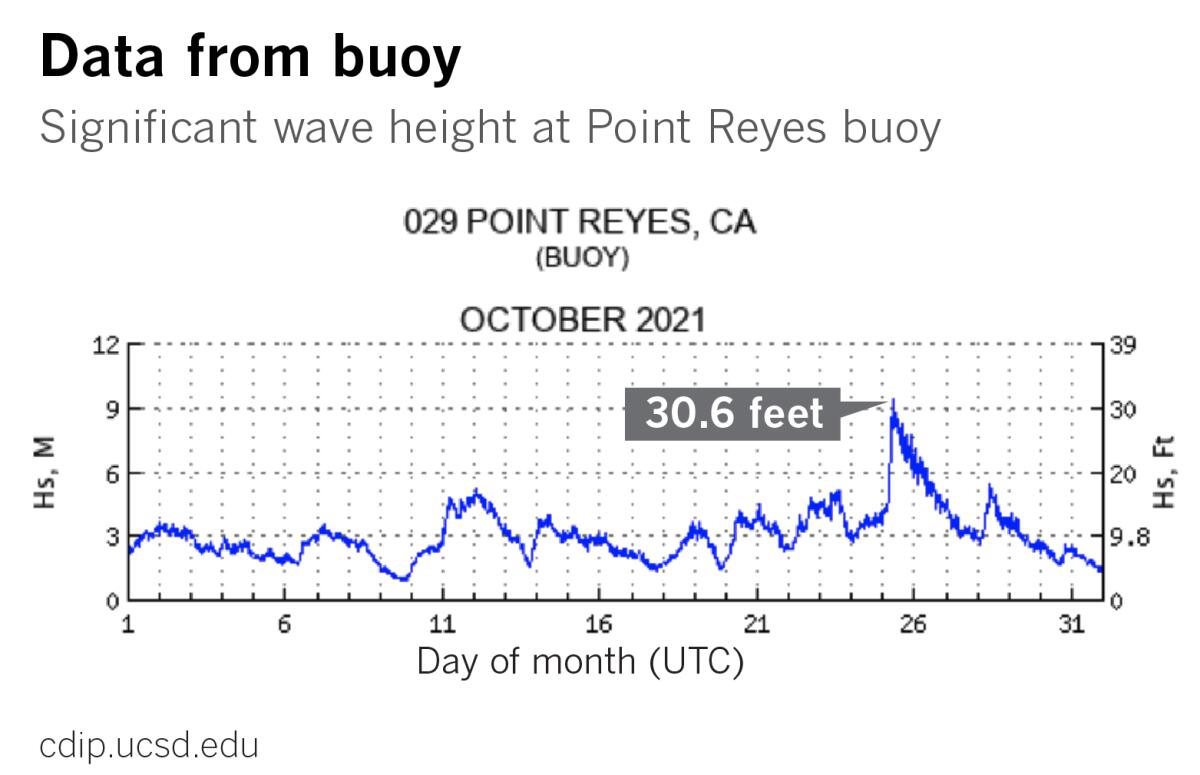

For example, the No. 29 Point Reyes buoy, located in 1,805 feet of water 25 miles west of Point Reyes, recorded a significant wave height of 30.6 feet on Oct. 25. That’s the second-largest wave event in that buoy’s 23 years of recording data. Only in December 2015, an El Niño year, did it record bigger waves.

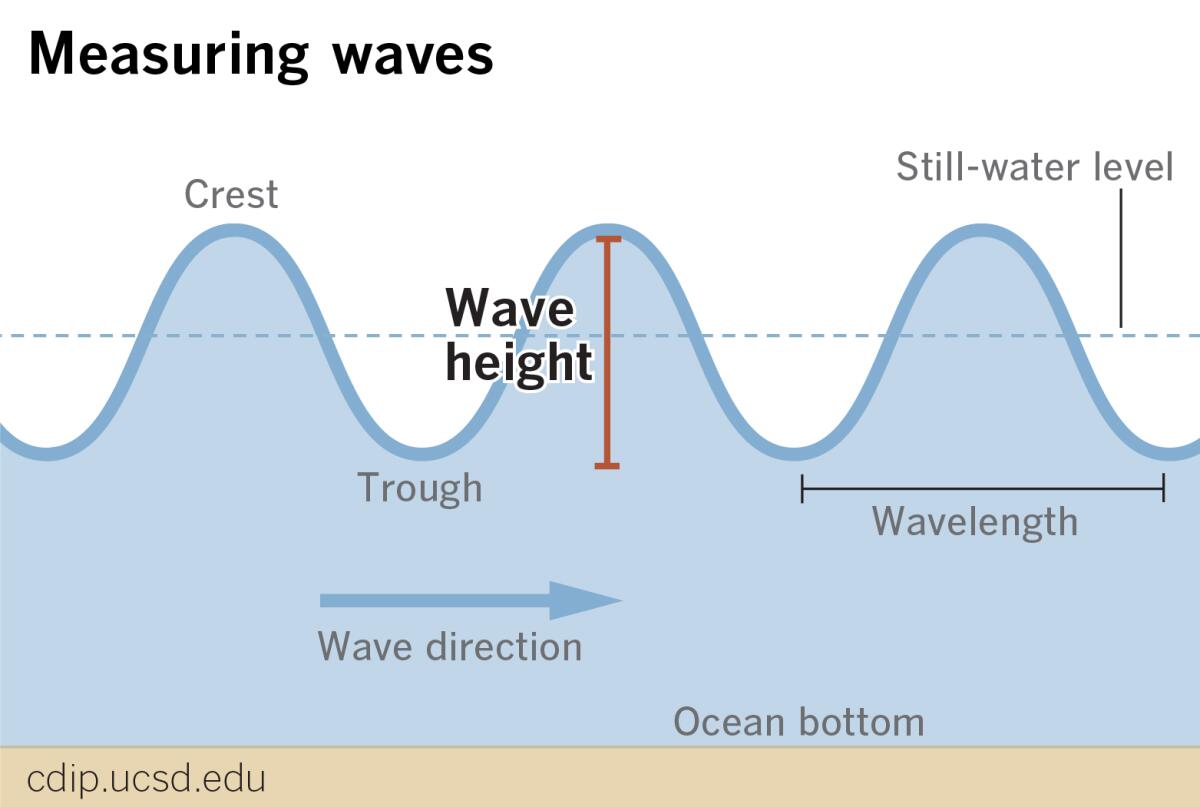

Significant wave height is calculated by averaging the height of the biggest one-third of waves during a 30-minute period, according to James Behrens, a program manager at the Coastal Data Information Program (CDIP). Typically, some individual waves at a given station can jack up to as much as twice that average, and the Point Reyes buoy recorded a maximum individual wave height of 50.5 feet.

To the north, the No. 179 buoy off Astoria, Ore., recorded significant wave heights of 35 feet, with individual waves slightly over 60 feet. This set a record for the station, which came online in 2011.

Later, as the storm weakened and the front sagged down the California coast, the No. 71 Harvest buoy, in 1,791 feet of water west of Point Conception, recorded a significant wave height of almost 30 feet, with a maximum individual wave height of 50 feet.

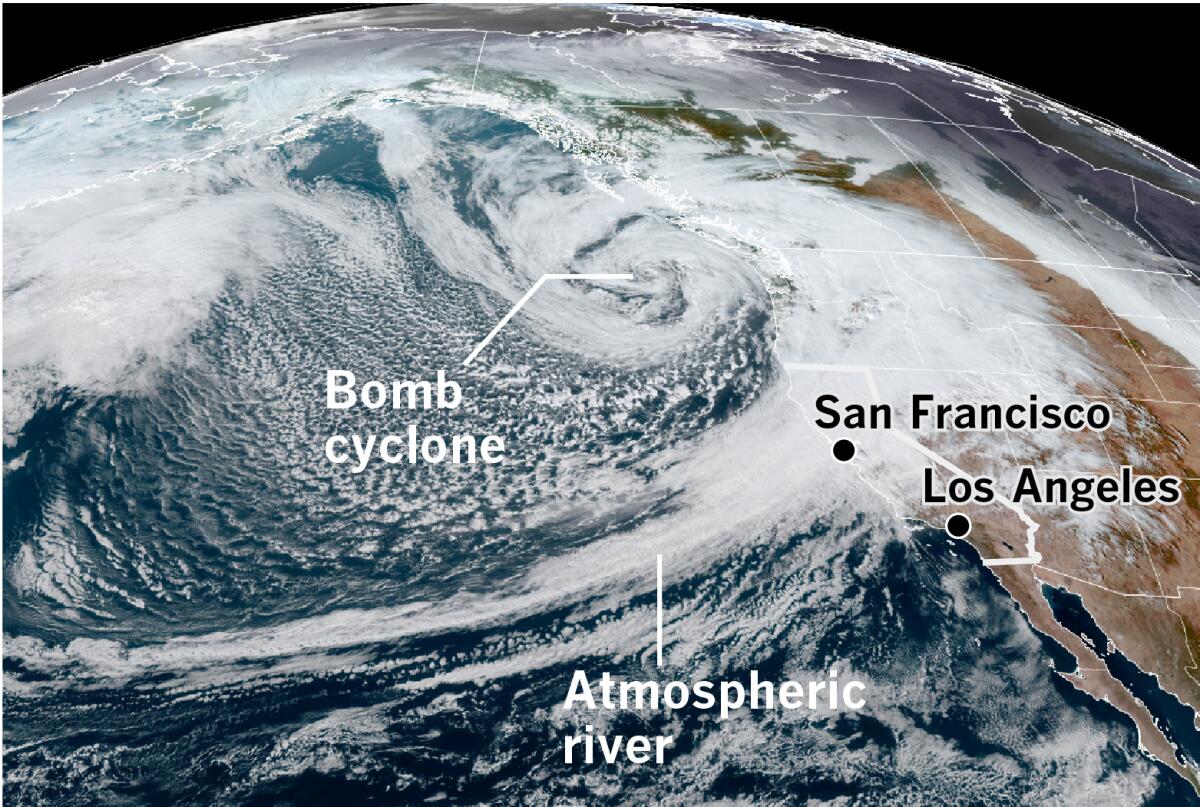

The deep low-pressure system that generated these historically large and powerful waves was churning off the Washington coast. It was part of a series of storms and atmospheric rivers that hit the West Coast in quick succession from Oct. 19 to 24. It had undergone explosive intensification called bomb-cyclogenesis, which means its central pressure dropped at least 24 millibars (a measure of pressure) in 24 hours. Generally speaking, the lower the atmospheric pressure, the more intense the storm.

Mid-latitude or extratropical cyclones such as this are low-pressure systems that generally occur between 30 degrees and 60 degrees latitude in the Northern Hemisphere.

This was the second bomb cyclone to develop in this part of the eastern Pacific Ocean in a few days. When its central pressure dipped to 942.5 millibars on the morning of Sunday, Oct. 24, it set a record for storms in this part of the ocean off the U.S. Pacific Northwest, and was equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane. The Saffir-Simpson scale classifies hurricanes based on wind speed and central pressure. At the time, the storm was about 345 miles west of Aberdeen, Wash., and its winds were raking Northern California and the Pacific Northwest.

The waves produced by the ferocious storm were large, but according to a summary by the National Weather Service in Monterey, forecasters were most impressed by the amount of wave energy pushing up onto the beaches. For example, they noted that water overran most of the beach at Carmel, and splashed rhythmically against the sea wall. Similar scenes elsewhere suggest that beaches were still in their summer configurations. In other words, not yet sculpted by winter storms, so not as steep and without significant protective sand bars — wholly unprepared for such a potent early-season blast.

Satellite images depict a classic comma-shaped system, with the deep low spinning counterclockwise off the coast of Washington State, and a moisture plume stretching back to the subtropical Central Pacific. This formed the tail of the comma. Remnants of Typhoon Namtheun, which had dissipated west of the International Date Line on Oct. 19, contributed to the plume.

This atmospheric river was the strongest to make landfall over San Francisco since January of 2017, and the fifth-strongest since 2000, according to the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes. This was the first exceptional atmospheric river to hit the region since February 2015, and was the strongest October atmospheric river to make landfall in the Bay Area in 40 years. Drenching rain caused flooding and triggered multiple mud and debris slides in Northern California.

The atmospheric river was like a fire hose trained on Central and Northern California, reaching its peak strength, a category 5, near Point Reyes, hammering Marin and Sonoma counties with its heaviest moisture transport around midday on Sunday.

As the storm abated in Northern California on Monday, Oct. 25, the sound of drumming rain was replaced by the buzzsaw-like whine of jet skis. Tow-in surfers at Mavericks, the surf spot south of San Francisco at Half Moon Bay, took up the challenge of the post-bomb cyclone waves. Surfline reported “Victory-at-Sea conditions,” surfer parlance for big, ugly, stormy waves. The expression comes from the 1950s NBC television series of the same name about naval warfare during World War II.

Notably, CDIP includes last month’s West Coast bomb cyclone on a page of wave observations, along with East Coast hurricanes and Nor’easters.

CDIP, at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, operates more than 30 active buoys along the West Coast with its partners, and is part of a network of about 80 stations that also cover the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts, and locations in the Caribbean, according to Behrens, the program manager.

Behrens said that his research group studies the wave data from buoys because erosive storms such as the recent bomb cyclones “are as powerful as the hurricanes on the East Coast, and the coastlines are taking the brunt.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.