- Share via

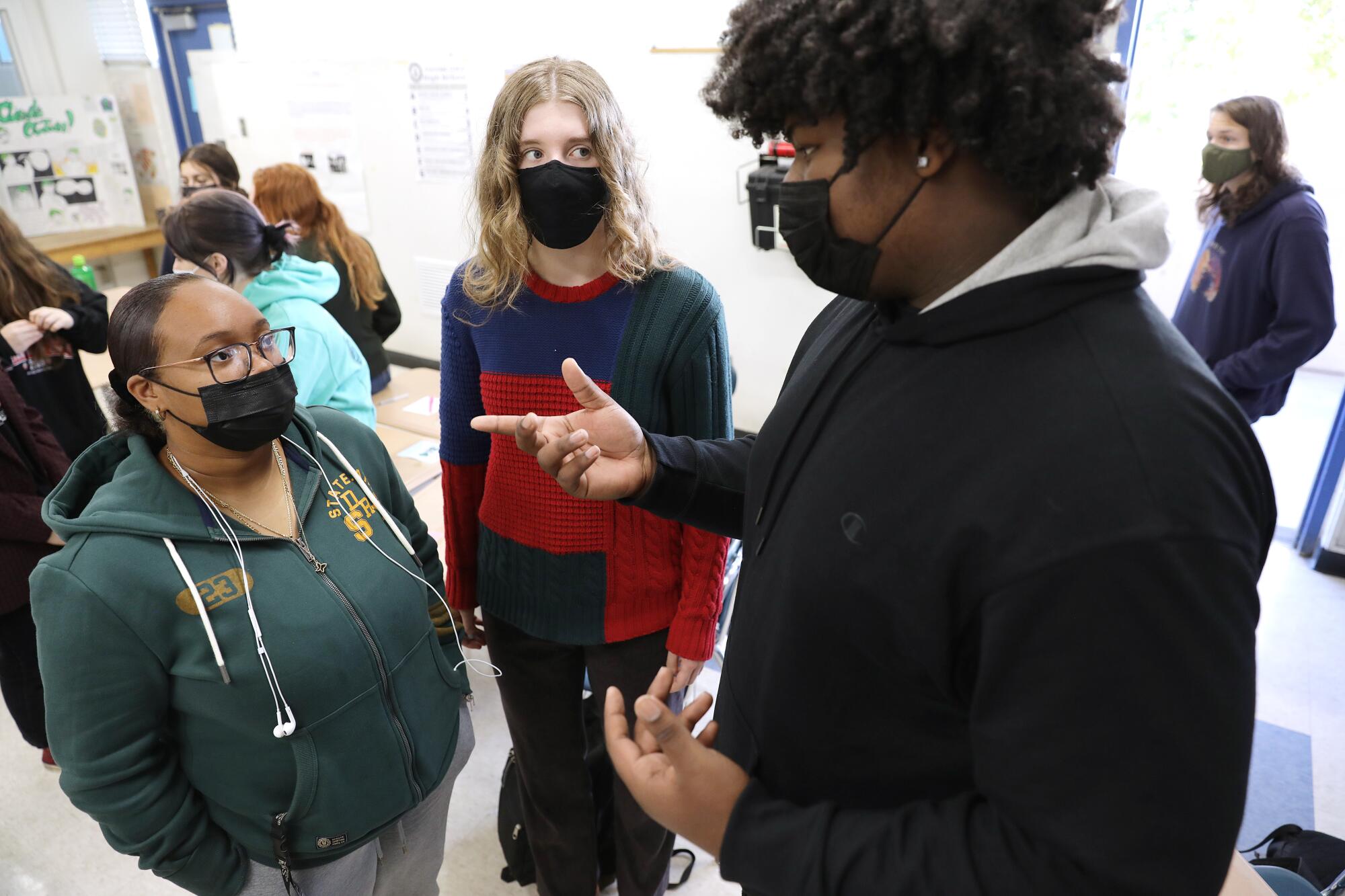

Huddled together, Culver City High senior Talaya Poindexter and her classmates considered the question at hand.

What is settler colonialism?

“A group of people coming into another person’s land or any space, or property or territory, and replacing their beliefs with theirs, and their traditions, and taking over their culture,” Talaya said to the group. The three others nodded in agreement.

Earlier in the week, the students watched videos and read articles about the nation’s Indigenous population, including the insensitive use of their culture for sport team mascots. Just the day before, Talaya said, she read an article about how Native children were separated from their home by the U.S. government and forced to live with white families, a symptom of the legacy of settler colonialism.

“It’s very heartbreaking, you know, because not a lot of us learn about this every day in regular history class,” she explained.

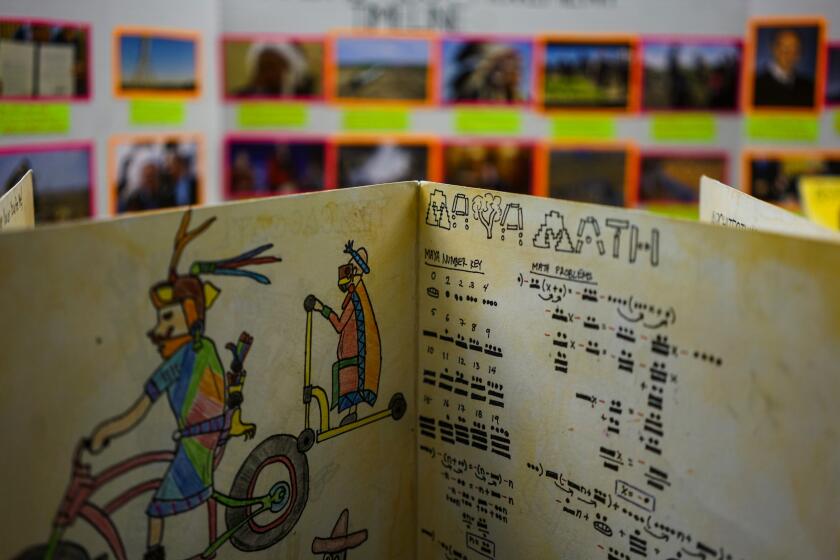

But this is no regular history class. It’s an example of what’s ahead for every California high school student who will be required by 2030 to take an ethnic studies class to graduate. Over the course of the semester, Talaya’s class has discussed how identity can be defined through race and ethnicity; students learned about the five faces of oppression; were introduced to resistance movements such as the fight for Mexican American studies in Tucson; they read about the Native Americans who once called California their home.

At a time when schools throughout the country are under siege for how race and history are taught — with at least 12 states passing legislation to limit the discourse — California is barreling in the opposite direction, the first state to mandate a high school ethnic studies course. The California law envisions a class designed to help students understand the historic and ongoing struggles of marginalized people — Black, Latino, Asian, Indigenous Americans and others.

Gov. Gavin Newsom signs an ethnic studies bill that represents a compromise between supporters and critics, but some in both camps remain dissatisfied.

But ethnic studies courses have been dragged into political attacks by conservatives and right-wing activists against critical race theory, an academic framework used mainly in universities that examines how race and racism are embedded in American institutions, policies and law. Ethnic studies in California high school classrooms encourages students to think more broadly about history by considering the perspectives of other groups, races and cultures.

The state law allows school districts to design courses that are particularly relevant to their communities. For instance, a high school in East Los Angeles may delve deeply into the Chicano movement while in Glendale, schools could decide to examine the Armenian immigrant experience.

Yet, in California, too, activists have invaded school board meetings — often in communities outside their own — to protest ethnic studies curricula in Los Alamitos, Placentia-Yorba Linda, Tustin and Paso Robles.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

And far removed from the angry shouting and politics are California students like Talaya and her classmates, whose respectful yet frank discussions about race, power and colonialism unfolded in Kimberly Young’s Culver City class throughout the fall semester.

A look inside two elective California ethnic studies classrooms at Culver City High and Edward R. Roybal Learning Center in the Los Angeles Unified School District shows teachers’ intent on creating an environment without judgment, one where students are learning as much about their own cultural roots as those of others.

◆

After discussing the meaning of settler colonialism, Talaya’s group broke up and assembled with other classmates to tackle the next question.

What might amends to Indigenous communities look like for participants in settler colonialism? How could we make it right?

“They inherently have less generational wealth than white people, so I think reparations is a way to kind of make the playing field more even,” said Ariana Moss, 16, noting that Native Americans have a harder time finding employment. “What do you think?”

Her classmate, Mason Merriwether, 16, picked up.

“I think we can start by trying to view the land as they view it, because as Ms. Young said, they view the land as life, and we view it as property to own,” Mason said. “We can start to see the land from their view, as it was their land, so I think we can start from there. Even if it’s something that I still think would take a while.”

“I know that oil drilling on reservations is also a big issue,” Ariana said, “so not doing that anymore, because that’s really disrespectful to the land. And like you were saying that this idea that ‘land is life,’ and that it’s part of the ecosystem, oil drilling completely just disregards that and I think that’s not acceptable.” Mason hummed in agreement.

The conversations around Young’s classroom were thoughtful, and students referenced articles they read or videos about how laws created inequities for Indigenous populations. At one point, Young opened up a question to the entire class:

Of the five elements of oppression — violence, exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism — which ones, their teacher asked, relate to settler colonialism?

“Genocide is such an inherent part of settler colonialism,” one student offered. “It leads to violence.”

“Powerlessness,” another student added, “because you make the people that you push out powerless.”

And one student offered a connection to all five: “In order to take their land, you have to leave them powerless, exploit them, culturally take everything from them in order to be settled, to colonize the land. So the five faces of oppression kind of go hand in hand with it because oppression is colonization.”

“Wow,” Young replied. “That was like boom, the whole thing, done.”

Classroom discussions challenging historical narratives are typical for Young, who has taught ethnic studies for six years after studying it at UC Berkeley. Young, who was appointed to the state Instructional Quality Commission by Gov. Gavin Newsom, has been a teacher for 15 years.

“I think that students are brilliant, and they have really important ideas, and my classroom provides an opportunity to challenge their thinking,” Young said. “I am asking them to think critically about the world around them.”

Young said recently she has sensed fear when talking about race because students and teachers are worried about saying the wrong thing.

To overcome this, Young said she works to make sure students feel comfortable asking questions. She uses part of her own identity, being Black and Mexican, to help students talk about their own.

“Often when we talk about race, we’re talking about problems, we’re talking about inequality, things that are very real in our society,” Young said. But “there are all these beautiful ways in which culture is really connected to race and ethnicity.”

Students in her class come from many backgrounds, reflecting the school district’s demographics. Culver City High is 36% Latino, 27% white and 16.5% Black.

Young said she understands topics that challenge Eurocentric history can be difficult. During her initial teaching years, she is not sure she could have had the expertise to lead her students through a discussion on settler colonialism, which is not an easy topic.

But after years of teaching the course, Young said she has a better grasp on navigating classroom discussions. It helps that her students, all juniors and seniors, are eager to have conversations about privilege and institutionalized oppression. Snippets of conversations revealed their awareness that non-Indigenous people have romanticized Native American culture and way of life while ignoring the trauma of neglect and poverty.

To Young, these conversations are key to understanding identity and power. But she fears that teachers may shrink from these topics.

“It’s like whiplash. We had the uprisings connected to the murder of George Floyd. Students in Culver City marched in the streets,” Young said. “Now we’re in a place where states are saying you can’t talk about it. So then how are students supposed to understand? Or where are these conversations taking place?”

◆

Across town in the Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles, Melina Melgoza, a teacher at Edward R. Roybal Learning Center, credits the California legislation for validating the mission of ethnic studies classes.

“We owe it to our students to prepare them for an imperfect world because that’s what we live in,” she said.

Like many teachers, Melgoza molded lessons around her students so that they would see themselves reflected in the course material, covering Latino-led movements in the state. The administration at Roybal, a school that is 88% Latino, supports the class, which she has taught every quarter for the last three years.

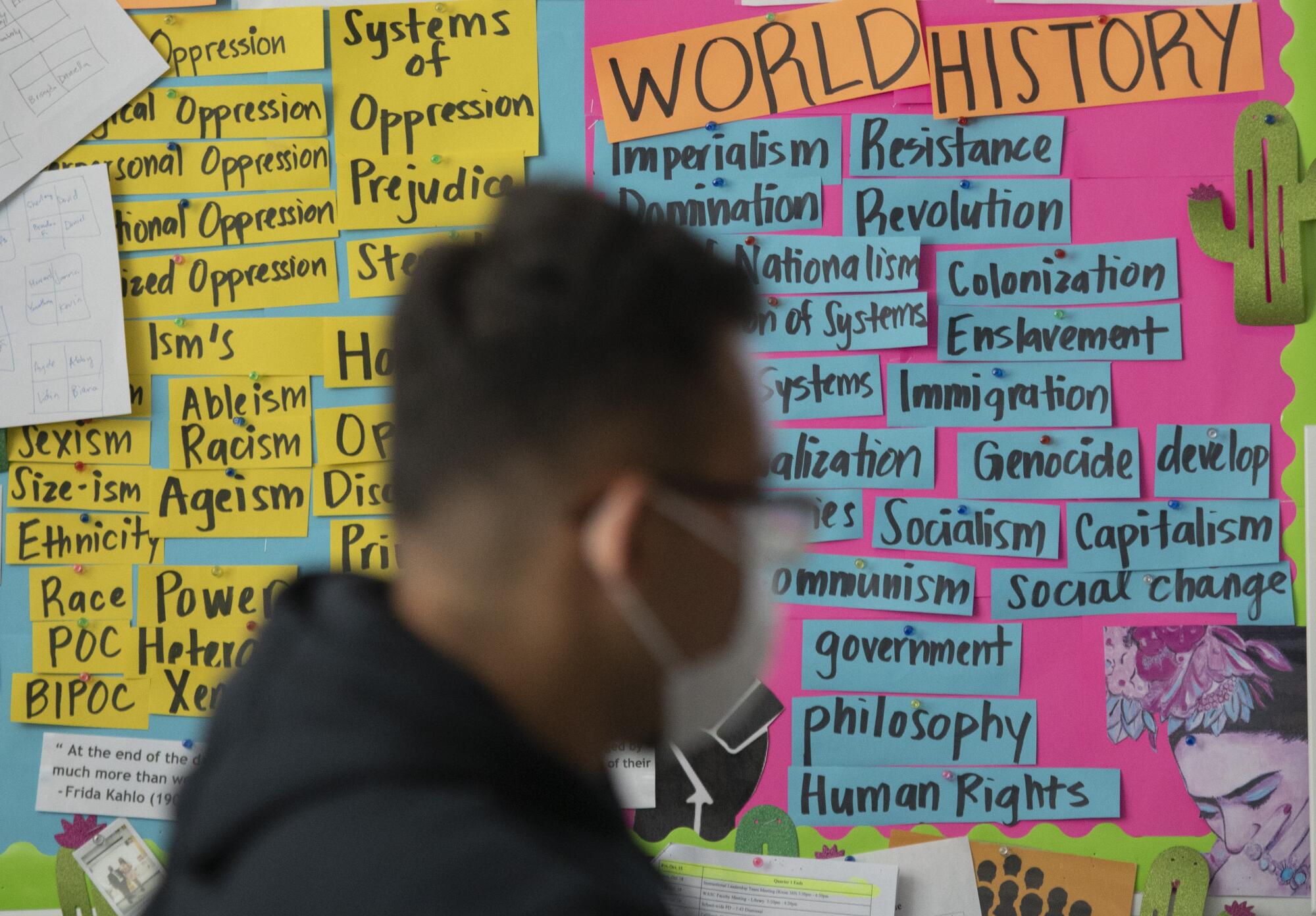

Like Young, Melgoza covers identity and the consequences of settler colonialism. The longest units in her class focus on historical movements: the civil rights movement, Chicanx and farmworkers, women and the LGBTQ rights movement. She has them answer questions such as: What role have young people played in social change? What role does self-determination play in social justice?

Most days, Melgoza starts her class with students completing a social-emotional learning check-in with their feelings. She then gives them a few minutes to scribble down their pensamientos, or thoughts, anything that was on their mind.

On a recent Tuesday, Melgoza launched her ninth-graders on their final project, which used a Tupac Shakur poem about a rose that grew from concrete. She asked them to identify the concrete and the petals in their lives; to think about what their obstacles are and who grounds them. In one of the last sections, she had them write down their “sun,” or legacy that they wanted to leave behind.

At the end of the week, students turned in large drawings of flowers, with their aspirations, struggles and hopes for the future.

“College is something really important to my family and I, it will also get me a good paying job,” one student wrote. “Owning a house is a dream I’ve always had since I was young and making the dream come true will mean a lot.”

“I want people to remember me by looking at what I created and seeing the change I made in our community,” another wrote. “As my grandma and cousins would say, ‘sí se puede.‘”

“Without [racism] the world could be a better place,” another wrote. “Also without racism all people of color can get together better and get along. If there was no racism then it could be easier for others to live.”

Melgoza’s classroom decorations feature terms such as “ageism,” “privilege” and “sexism.” On one wall, below essays that received perfect or near-perfect scores, is a message: You are safe here.

In a class where a majority of students were teenage boys, they spent time discussing and defining toxic masculinity, which can be described as a “tough guy” mentality, and the effect of social norms on how emotions are labeled as feminine or masculine. They also talked about the consequences of such behavior, Melgoza said, and she watched as some of her students’ behavior improved afterward.

Signs declaring “Black Lives Matter” are scattered along the walls, along with reprints of Latino icons like journalist Ruben Salazar and poet Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales.

It was in Melgoza’s classroom that her students first learned about the Chicano movement that unfolded in their Los Angeles neighborhoods.

“The L.A. walkouts actually happened in our community, right across the street,” sophomore Bryant Barillas, 15, said in class. “To this day, we’re still fighting for equality.”

Melgoza has spent weeks showing her students movements that transformed the nation and she has not shied away from what she sees as the reality of the country today.

“[Equality is] still a process, and I don’t know if there’s a finish line,” Melgoza replied. “It’s still a constant struggle.”

Sophomore Diego Barrera saw this reflected in how the transgender community is still fighting for equal rights.

“This country has a short history compared to other countries in the world, and we have a lot of things that we still need to fix,” Diego reflected.

Melgoza said she has watched her students create a community with one another. Sometimes, they come to class with questions about the current news of the day, such as the end of the war in Afghanistan, why Instagram crashed for several hours and understanding the Texas abortion law.

When these issues arise, she said, she answers her students’ questions without imposing her beliefs, and she makes sure her students have a chance to share their thoughts. Other times, they connect classroom material to their own lives.

Senior Julian Canales said learning about the Zoot Suit riots and the L.A. walkouts, which were led by young Latinos, served as reminders that young people can change the world.

Former students of ethnic studies have said the course shaped their views on the role of race in society.

After completing Melgoza’s ethnic studies course, Karen Reyes said she left the classroom each day more open-minded. She felt comfortable learning about her own identity, and it became easier to identify injustice in her everyday life after learning about the different forms of oppression.

Now a student at Cal State L.A., she credits the course for making her think critically about how racial bias can contribute to inequitable healthcare for women of color.

She aspires to become a nurse who is cognizant of the role of race in patient care.

“I will listen to them,” Reyes said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.