After 30 years in the political spotlight, Ridley-Thomas is suddenly under a cloud

- Share via

Over three decades, five mayors have passed through Los Angeles City Hall. A major earthquake and civil insurrections have shaken the city. A pro football team left and two others arrived.

Through it all, there has been a constant presence in the city’s political leadership: Mark Ridley-Thomas, the onetime civil rights activist turned city councilman, then state legislator and county supervisor who returned as a councilman late last year.

Ridley-Thomas’ legacy as one of the city’s bright young political lights and then an establishment figure who won nine straight elections became clouded this week by a federal indictment that accuses him of taking bribes from a USC dean in exchange for directing millions of dollars in public funding to the university when he was on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors.

The 20-count indictment charges Ridley-Thomas and the former USC administrator with conspiracy, bribery and mail and wire fraud, threatening to end the career of a man who has been a seemingly immovable figure in the politics of South Los Angeles since the 1990s.

“It’s a Shakespearean tragedy. This is something he has done to himself. This is a self-inflicted wound for him and his family,” according to Dermot Givens, a lawyer and political consultant, who said Ridley-Thomas deserves the chance to defend himself before judgment is rendered. Still, Givens added: “It just makes no sense, what has happened.”

Many are rising to defend and pray for the councilman, while calls escalate for him to step down or, at the very least lose, his committee assignments.

Through his lawyer, Ridley-Thomas expressed shock at the charges, which attorney Michael J. Proctor called “wrong.” He added: “At no point in his career as an elected official — not as a member of the City Council, the state Legislature or the Board of Supervisors — has he abused his position for personal gain.” Proctor asked the public “to allow due process to take its course.”

In a statement Friday, Ridley-Thomas said he has “no intention of resigning my seat on the City Council or neglecting my duties. Doing so would be to the detriment of the people I serve, and I have no intention of leaving my constituents without a voice on matters that directly affect their well-being.”

He said he intended to “disprove the allegations leveled at me” and continue working on the crises of homelessness and housing.

Ridley-Thomas supporters said privately this week that they hoped the public would view his case differently than those against other L.A. politicians, including former Councilmen Jose Huizar and Mitchell Englander.

Huizar was still on the council last year when he was indicted on federal charges of aiding real estate developers, who handed over bribes that included cash, free flights, casino chips and other perks. Englander pleaded guilty to a single count, after accusations that he took envelopes with cash and other lavish perks in casinos in Las Vegas and near Palm Springs.

Ridley-Thomas, 66, is accused of a scheme in which his son Sebastian Ridley-Thomas won a scholarship from USC and a professor’s position around the time that his father — while serving as a county supervisor — funneled campaign money through the university, which ended up in a nonprofit group run by his son.

Because of the lack of a direct benefit to the city lawmaker, Ridley-Thomas is likely to mount a protracted and spirited defense, said Fernando Guerra, a political science professor at Loyola Marymount University.

Already unsettled by the likely departure of the mayor, an upcoming election and a contentious redistricting process, the City Council must decide what to do about Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas.

“If I were Mark Ridley-Thomas, I would not resign,” Guerra said. “He is too important a voice.” The political scientist said Ridley-Thomas “helped shape the progressive narrative and agenda in Los Angeles and in California for the last 30 years.”

There was nothing in Ridley-Thomas’ early life or start in political activism to hint at the turmoil that would come late in his career.

He grew up in South Los Angeles and graduated from Manual Arts High School, before earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees and a teaching credential from Immaculate Heart College. He went on to receive a PhD in social ethics from USC, his research focusing on social criticism and social change.

Ridley-Thomas then served for 10 years as executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Greater Los Angeles, with one focus being on police practices in neighborhoods of color.

He was first elected to the City Council in 1991. The 36-year-old newcomer made his first mark on the somewhat staid 15-member council by calling out what he perceived as racially insensitive slights by a couple of his older, white colleagues.

But Ridley-Thomas’s last impression at City Hall was not as a firebrand but as an adept political tactician. When the council raised a business tax to close a budget shortfall early in his tenure, he negotiated a waiver of the hike in impoverished areas, such as his South L.A. district.

After the 1992 riots, he passed a planning law that allowed liquor store owners who lost their businesses to build back bigger, but only if they agreed to discontinue alcohol sales.

He also directed a special committee on water rates that shifted more of the fee burden away from the inner city and onto the suburbs. And he was one of the most persistent voices at City Hall for reforming the Los Angeles Police Department, serving on a committee charged with enacting the Christopher Commission reforms.

Among those who are dedicated to alleviating homelessness in Los Angeles, the news of the indictment of City Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas brought only sadness and dismay.

By the time he left the council in 2002, even some of his past critics rose to laud him. Fellow City Councilman Nate Holden said Ridley-Thomas had pumped new life into the 8th District, including “more parks, more recreational facilities, more businesses and better services.” Councilwoman Cindy Miscikowski called him “the moral compass in standing for civil justice.”

That’s not to say that Ridley-Thomas was universally loved. By the time he was running in 2008 for a seat on the county Board of Supervisors, there were some who had come to see him as pompous and abrasive. His tendency to long-winded oratory had grown tedious to some. He feuded with longtime U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles), who said, “Mark is seen as arrogant, egotistical and disrespects folks.”

But that did not stop him from defeating the favorite for the board seat, former police chief and City Councilman Bernard C. Parks.

As one of the county’s five supervisors, Ridley-Thomas oversaw the revamping and reopening of Martin Luther King medical center in Willowbrook, the hospital where emergency service had been shut down after excessive patient deaths. He also led the fight to get a Leimert Park station added to the Crenshaw-to-LAX light rail line.

In 2017, he became a leading voice for Measure H, the sales tax hike that is adding an estimated $355 million a year for rent subsidies, shelter beds and other services to try to curb homelessness.

Though the problems of the unhoused have continued to spiral, Ridley-Thomas has been viewed as one of the leaders most willing to confront the problem. Acknowledging the slow pace of building permanent housing, he has pressed to open more shelters, so-called tiny homes and interim structures of all kinds.

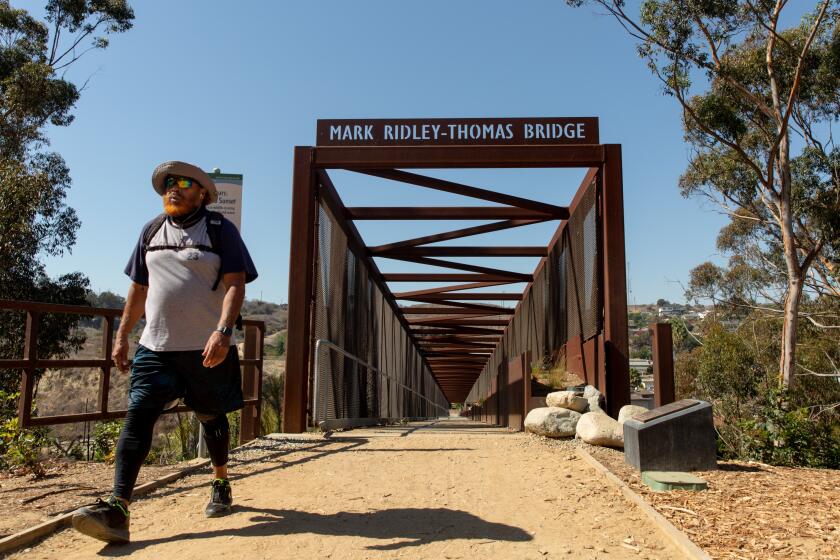

Federal charges have cast a shadow over the many sites named after longtime politician Mark Ridley-Thomas, whose name has decorated health centers, a youth facility, government offices and a pedestrian bridge.

While at the county, his stumbles were modest. He took some flak for spending that some perceived as not in the public interest. He used $25,000 in taxpayer money in 2010 to buy a place in the publication “Who’s Who in Black Los Angeles.” He said the publication highlighted the good works being done by himself and others, which is important in showing Black leadership in action.

In 2014, taxpayers spent about $10,000 for a security system at his Leimert Park home. The work included improvements to his converted garage and upgrades to the building’s electrical service.

None of those tempests did any serious damage to Ridley-Thomas. By 2020, term limits required that he leave the Board of Supervisors, and he ran to return to the City Council, where his political career had begun.

Nearing retirement age, he was no longer the brash young man who first came to City Hall 30 years ago.

L.A. County Supervisors Hilda Solis and Kathryn Barger want to see an independent audit of their former colleague Mark Ridley-Thomas.

While one opponent called for cutting the Police Department’s budget in half, Ridley-Thomas vowed to maintain it, saying the LAPD needed adequate staffing to provide community policing. Similarly, he rejected a call to eliminate all fares on trains and buses under the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, saying the system simply could not afford it.

With term limits putting him in his last stint on the City Council, many in City Hall had been convinced Ridley-Thomas would declare his candidacy for mayor. But in August, Ridley-Thomas said he would not run. He said he could focus more intently on the all-important issue of homelessness if he remained in his council seat for three more years.

“My calling and focus is that of the homeless crisis in the city of Los Angeles,” he said, “and I will double down and lean in on that particular issue.”

Former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa said he was surprised and saddened by the charges against his longtime political ally.

“I am praying for his family in these times,” Villaraigosa said, “and hoping that all of this can get sorted out for the good.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.