- Share via

Perched high above the waves about nine miles off the coast of Huntington Beach, the oil processing platform known as Elly looks like an industrial eyesore — a tangle of hard metal surfaces, cranes and pipes.

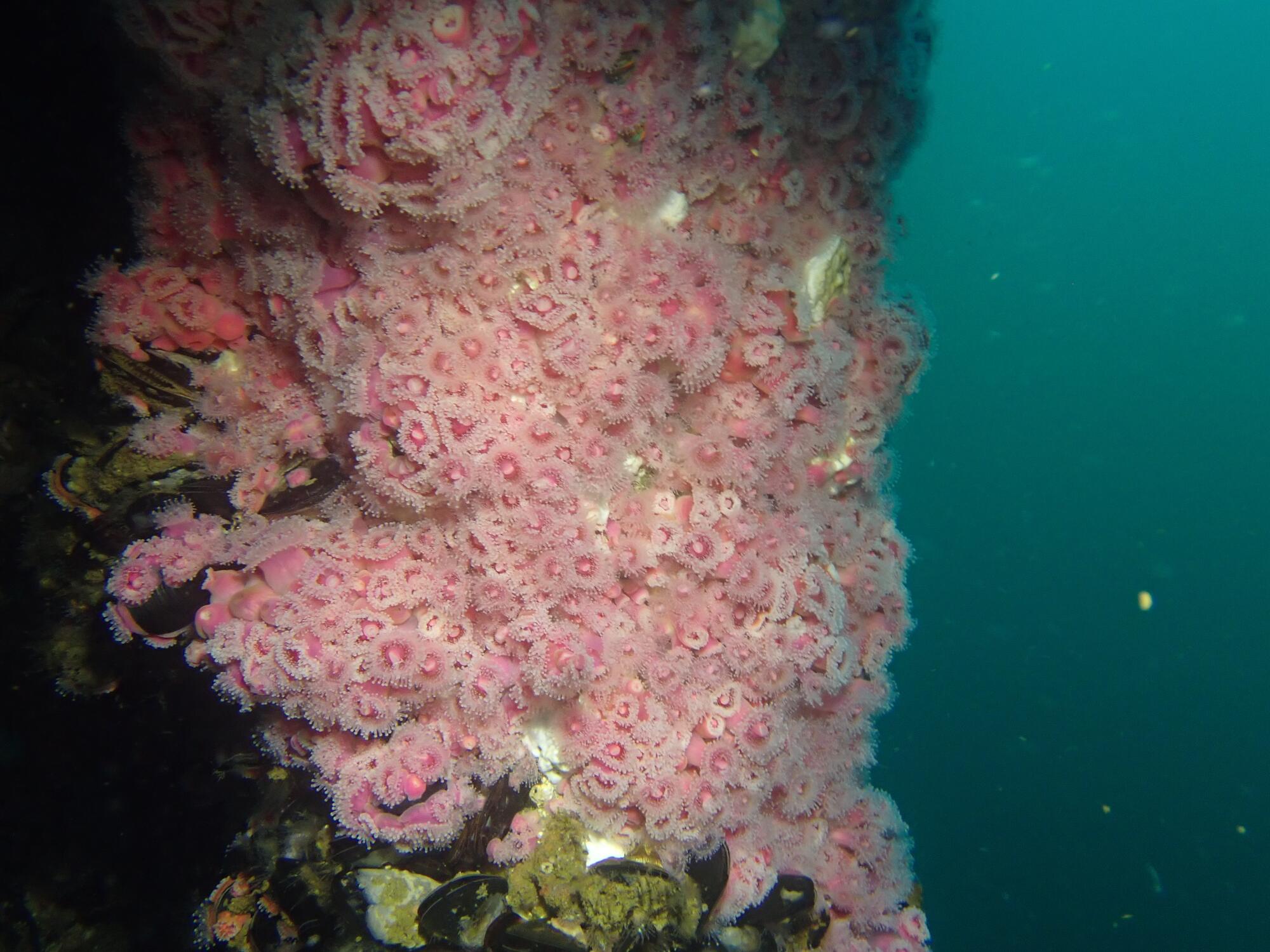

But plunge 30 feet beneath the waves, and you enter a psychedelic wonderland of undulating marine life. Mussels, anemones and brittle stars coat the platform’s thick steel pilings, sea lions frolic between its beams and tens of thousands of fish dart between its supports. Neon nudibranchs (small sea slugs) wander among the other life. Sponges, scallops and corals are all part of the mix.

No wonder the Elly platform is one of the most beloved dive sites in Southern California.

“It’s my No. 1 favorite dive,” said Paige Zhang, a graduate student in marine biology at UCLA who spent a day diving Elly just a few weeks ago. “And that’s why I was so shocked and sad about this spill. It’s so crazy to think that this happened on something I dove before.”

Details about the scope of the recent oil spill in Orange County are still murky, but officials say as much as 144,000 gallons of crude oil leaked from a 17.7-mile pipeline that runs from the Elly platform to the Port of Long Beach. Exactly where and how this leak occurred is still being determined.

Scientists and environmental groups rushed to protect the diverse animal populations in the region’s marshes and wetlands — deploying booms to keep oil from flooding and rescuing birds who are already exhibiting obvious signs of oil damage.

As of now, nobody knows for sure how the oil spill will affect the abundant marine life living on the rig itself.

Oil is lighter than water, so the good news for these creatures, who live tens and hundreds of feet beneath the waves, is that the vast majority of it has probably risen to the surface. But there’s bad news too: Even trace amounts of oil can be deadly.

“I don’t know if the platform itself or all the organisms that have attached to it have been coated with oil, but we know that even small concentrations of oil in the water can have toxic effects,” said Andrea Bonisoli Alquati, a biologist at Cal Poly Pomona who studied the aftermath of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. “It doesn’t take a lot of oil to kill these small organisms.”

“It’s an oasis in the middle of an ocean desert. You’ve got nothing but deep water ocean surrounding it.”

— Ashley Arnold, owner of Jade Scuba Adventures

It’s not a surprise that animal life has congregated on the submerged infrastructure of Elly, said Milton Love, an ichthyologist (fish scientist) at UC Santa Barbara who studies how rigs function as fish habitat.

“There are always more invertebrate larvae drifting around looking for a place to settle on then there are places to settle on,” he said. “And then here is this humongous structure with 1,200 feet of steel — that’s a lot of stuff to settle on.”

Over the years, he’s discovered that organisms aren’t always picky about where they make their homes.

A massive oil spill off the Orange County coast has fouled beaches and killed birds and marine life

Lobsters have been known to live in submerged toilet bowls, while sarcastic fringehead fishes (yes, that’s their real name) have been found living in beer bottles that landed on the ocean floor, he said.

“You can take an old inner tube and throw it right off of Long Beach in 80 feet of water, and in a couple of days there will be three brown rockfish staring at the tire,” Love said. “They are attracted to stuff. They don’t care what the stuff is.”

As more offshore platforms are likely to be decommissioned in the next few years, both in Southern California and elsewhere, there has been discussion about leaving the underwater parts intact because of their value as artificial reefs.

As a scientist, Love said he’s neutral on the issue. As a human being, he’s not.

“Pulling out a platform means killing huge numbers of marine life, and I don’t think that’s moral,” he said. “That has nothing to do with being a biologist. That’s just my moral stance.”

The abundance of life around all these structures is so notable that a 2014 paper in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences declared oil platforms off California one of the most productive marine habitats globally.

Still, Love said there is something particularly special about Elly and the rig sitting right next to it, known as Ellen.

“The people in my lab and myself have been around almost all the platforms in California, and Elly and Ellen have an unusually high diversity of fishes around them,” he said. “They are just great.”

Shawn Wiedrick, who until recently worked as an assistant curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, described his first dive around the Elly rig as “surreal.”

“There were organisms on top of organisms, it was so thick,” he said. “I was tasked with going down and sampling things, but there was so much there, it was almost overwhelming to say ‘What should I sample?’”

It’s that vast diversity of life that makes the rig so enticing to local divers, said Kevin Lee, an underwater photographer who has dived the Elly site more than 30 times.

Officials haven’t approved any new oil exploration off California’s coast in decades. Yet pumping and drilling continue there. Here’s why.

“It’s such a beautiful ecosystem,” Lee said. “The life is outstanding out there, and it’s much more colorful than what you would see on shore. For some local divers it’s their favorite dive site.”

Ashley Arnold, owner of Jade Scuba Adventures, who works out of Huntington Beach and Port Orchard, Wash., remembers seeing strawberry sea anemone, spiky acorn barnacles, and a dazzling array of nudibranchs, some with spikes shooting off their soft bodies.

On a dive trip to Elly and Ellen in January, she captured video of four types of bioluminescent jellyfish — alien-looking life forms that floated through the water. She also saw a wide variety of fish, including bright orange garibaldi, blue-and-silver halfmoons and several types of rockfish.

“It’s an oasis in the middle of an ocean desert,” she said. “You’ve got nothing but deep-water ocean surrounding it.”

Arnold said rig diving is best for experienced divers: Having good buoyancy control is critical to staying safe when swimming among the pilings and supports, and the ocean currents can be volatile. Sometime there’s no current; other times “it’s super crazy ripping.”

“It’s completely unprotected out there,” she said.

To get to the rig, divers generally charter a boat from Long Beach or San Pedro. It can take 45 minutes to an hour and a half to get to the site, depending on the speed of the boat. Divers also need to get permission from the rig’s operator before they head out.

“They are active rigs and working the entire time we’re diving, but if they have a crew coming out to do work on the structure we don’t want to be in their way,” Arnold said.

Norbert Lee, a dive instructor and marine biologist who works for L.A. County Sanitation, said that before the spill, he tried to do day trips to the rigs three or four times a year.

“We usually go between Ellen and Elly, and Eureka, which is a rig that’s a lot deeper,” he said.

His strategy is to quickly descend to the maximum depth of the dive and then slowly make his way up to shallower water — harvesting scallops to eat, and playing with sea lions along the way.

“Those scallops are super tasty,” he said. “It’s one of the best dive sites, to be honest.”

Lee is hopeful the cleanup efforts will be effective enough that he’ll be able to dive the rig again someday, but said “it’s hard to hear that it came out of a place that you dive so much, not to mention all the ecological impacts it has on the wetlands. It kind of broke my heart.”

Zhang said she and her dive friends immediately started texting back and forth when they heard about the spill.

“You hear about oil spills all the time on the news, and you feel like they are so far from your life, but this one is so close to all of us,” she said.

She worries about the millions of stationary animals on the rig who are unable to swim away from oil slicks. She wonders how she can help with the cleanup. And she thinks about when she’ll be able to get back into the water, and where.

Zhang got more serious about diving during the pandemic, and, as with many frequent divers, it’s now an essential part of her life.

“Once I’m down there, I just feel like my head is cleared, I don’t think about work, I don’t think about anything,” she said. “You are totally in the moment. It’s gotten to the point where I have trouble sleeping if I don’t dive for more than a week.”

Though not enough information has been released yet to make a prediction on when the waters around the rig will be safe for divers again, Love said there is reason to be optimistic that the animals that make their home on Elly will survive this ecological disaster.

Ten miles off the coast of Santa Barbara, another oil platform called Holly is situated among large natural seeps of oil and gas. Essentially, it is bathed in oil almost all the time, he said.

But when Love looked to see whether this platform could support marine life, he was stunned to discover it was covered in thriving sea creatures.

“We didn’t see a dead nudibranch or a dead anything,” he said.

Love thinks the animals were spared because all the oil had risen to the surface. And he’s hopeful the same will be true for the vast, diverse and beautiful life living on Elly.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.