How a Black lawmaker from L.A. won a ‘mammoth fight’ to oust bad cops

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — In 2019, Fouzia Almarou was speaking at a police reform rally at Rowley Park in Gardena when a man she didn’t know made her a promise she didn’t quite trust.

Gardena police had shot Almarou’s son, Kenneth Ross Jr., at the park a year earlier, and she was marking the one-year “angel-versary” of his death.

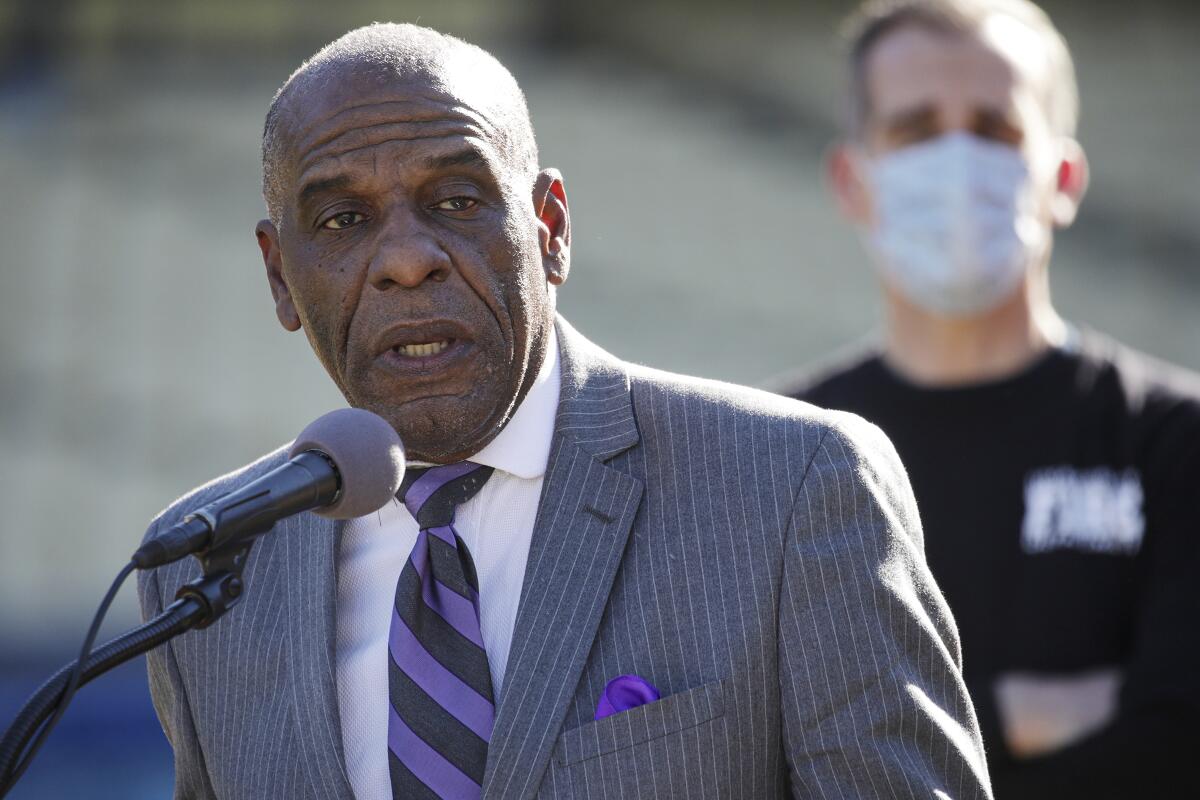

State Sen. Steven Bradford, who grew up in the neighborhood as part of the first Black family on his block, told the mourning mom that he was going to change California law in the name of her lost son. He would make sure that officers with questionable pasts couldn’t jump from one job to the next to avoid accountability.

“At first I didn’t know,” Almarou said Tuesday on her feelings about a vow from a politician she hadn’t met until that day.

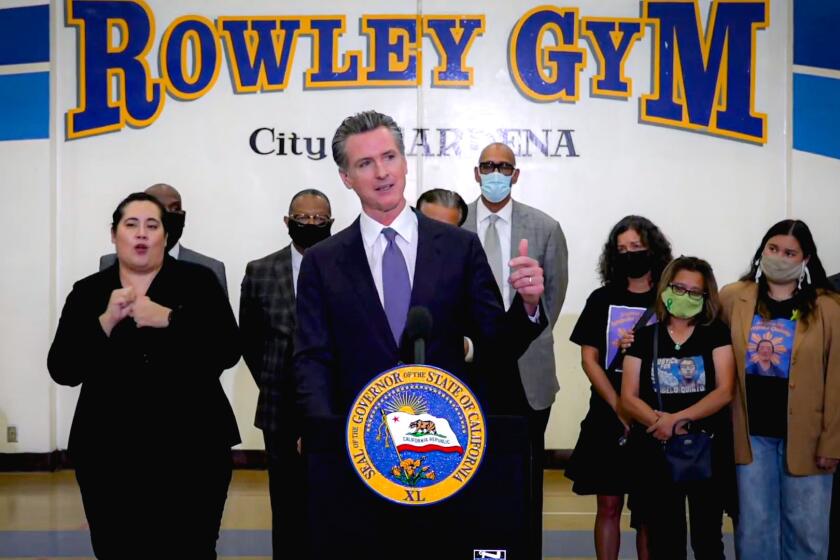

On Thursday, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the Kenneth Ross Jr. Decertification Act of 2021 at the gym inside Rowley Park, after what Bradford describes as a two-year “mammoth fight” to push it through the Legislature. The measure provides a pathway for revoking the licenses of law enforcement officers who commit serious misconduct, even if it does not rise to the level of criminal charges — preventing them from taking another badge-carrying job.

Until now, officers accused of grievous bad acts had the ability to find employment at another agency, even if they were fired, leaving California with what Bradford describes as a “wash, rinse, repeat” cycle of problematic officers.

Often, critics of the system contend, those officers end up policing in smaller jurisdictions, which may lack the resources to watchdog their conduct.

Bradford was drawn to the issue over concern that the Gardena police might unknowingly be helping launder a bad officer. When Ross was shot, Bradford said he was surprised when he did not recognize the name of the officer who pulled the trigger of an AR-15 twice, striking Ross in the back and shoulder. After 52 years living in the city, working as its first Black councilman, coaching Little League and football on Rowley’s playgrounds and founding the city’s jazz festival, Bradford knows just about everyone.

“Many of those officers I consider my friends,” Bradford said. “When I heard about Kenneth Ross Jr. being shot, I was like, this is so far out of character for Gardena PD.”

Gardena’s chief did not immediately return a request for comment. But when Bradford began calling around, he learned the shooter was a so-called lateral hire from Orange County — a fully trained officer who had switched departments and “really had no business being here in Gardena,” said Bradford. Then he learned the officer had been involved in what Bradford described as three other “questionable” shootings, though none were deemed illegal.

“That turned on the light for me that this needs to end,” he said.

At the time, California was one of only a handful of states with no way to decertify officers, belying its progressive reputation and leaving it far behind in guarding against bad policing.

“This isn’t even a radical demand,” said Black Lives Matter L.A. leader Melina Abdullah, whose organization was one of the main sponsors of the Ross Act.

The changes include raising the minimum age for officers to 21 and allowing badges to be taken away for excessive force, dishonesty and racial bias.

Still, Bradford’s proposal for a lifetime professional ban on bad officers quickly became one of the most heated reform measures at the Capitol as the pandemic unfolded and protests exploded following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. Across the country, police felt besieged and reformers felt empowered.

Under the Capitol dome, the status quo seemed unshaken. For a brief moment in 2019, the once unassailable power of law enforcement unions in Sacramento took a bruising with the passage of a new law regulating the use of deadly force, Assembly Bill 392, inspired by another Black man shot by police, Stephon Clark. Though that bill was softened by the time it passed, the law enforcement lobby had been taken off guard by its inability to stop it, but regrouped and came back strong, determined that their defeat would not become routine.

“Police unions are a powerful voice and probably only second to the teachers, so we knew we were going to be in for a fight,” said Bradford during an interview with The Times on Tuesday. “They threw everything at us.”

The original version of Bradford’s bill, Senate Bill 731, was a no-go to law enforcement unions who saw its provisions as going too far in stripping officers of protections and due process rights, and setting up a system they saw as biased against police.

In 2020, amid a strange legislative session that saw numerous bills fall by the wayside at the last moment, Senate Bill 731 wasn’t granted a final vote in the Assembly, with the Legislature simply timing out without taking it up — the kind of quiet dispatch that takes power to orchestrate.

Abdullah spoke with Bradford the night SB 731 went down, sharing his outrage, she said.

“We were appalled actually that in 2020, the bill wouldn’t pass. There was a lot of emotional energy,” said Abdullah. “We were beyond dismayed.”

But Bradford was “undeterred,” she said, starting the process of reviving the proposal the next day, working to smooth the controversial points that had initially built opposition.

But law enforcement still opposed the new bill, Senate Bill 2, and under pressure, Bradford lost his cool more than once. When the bill seemed like it might face a bureaucratic demise during an hours-long committee hearing, he pleaded with his colleagues, “If not now, when?”

In July, in response to a report about political donations by law enforcement, he tweeted, “Interesting this is how you try to kill solid policy? If you can’t win on the merit of your argument, you resort to paying off legislators?? SHAMEFUL, BUT NOT SURPRISING!!”

Where the federal government has failed, California enacted new laws that will finally address police misconduct and set an example for reparations.

Though the version under Newsom’s pen Thursday, introduced with California state Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins as a co-author, is weaker than Bradford’s original proposal, it remains one of the most significant reform measures to pass this year.

In the final version, a proposal to remove qualified immunity protections — which prevent officers from being held personally liable for their actions in federal court — has been scratched, and the protocols for stripping an officer of certification have also been tightened. Most significantly, officers can be removed from the profession only by a two-thirds vote of the law enforcement commission that ultimately decides the issue — as opposed to a simple majority.

Law enforcement — though supportive of the idea of decertification — continue to oppose the Ross Act, only acquiescing to its inevitability after a compromise brokered by Newsom. Much negotiation went into the effort, said Bradford, but “we made our minds up that if we had a bill that law enforcement liked 100%, then we didn’t have a bill.”

Law enforcement leaders fear nebulous language in the law that leaves unsettled what kinds of actions could lead to decertification. Some fear the civilian panel could still include those with a bias against law enforcement, and question why the law did not specifically acknowledge the state’s Peace Officers Bill of Rights, which gives officers certain protections.

Brian Marvel, President of the Peace Officers Research Assn. of California (PORAC), said that while his organization “supports establishing a fair and balanced licensing program that affords peace officers the due process rights all American citizens are entitled to,” those concerns will need to be hammered out as the law takes effect.

“There is still work to be done,” Marvel said in a statement.

Bradford said the bill isn’t meant to be anti-cop, but anti-corruption. As a young man, Bradford applied to the LAPD academy in 1981 — but, he said, when he answered certain questions on the background check, he was booted.

“I called [my friend], I was crying, saying, ‘Hey man, I just got a letter rejecting me,’” he said. His friend, a police officer, asked why he would have disclosed the disqualifying information.

“I thought we were supposed to tell the truth,” Bradford told him.

“I think about that often many days, “ he said. “Literally I woke up this morning thinking what kind of officer would I have been?”

Sadiha Ramirez, one of Ross’ sisters, said her family was happy the law will bear his name and that it could prevent future bad actors from remaining in the profession. But the moment is bittersweet. The officer who shot her brother retired after being cleared of wrongdoing by former L.A. Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey.

Lacey’s investigation concluded that the officer who shot Ross, Michael Robbins, was in fear for his life and the lives of others when he fired. Gardena police had been responding to a call about a man firing a weapon when Ross was seen running near the park. Officers chased him, but he continued to run despite their instructions to stop.

Robbins told investigators that he fired because he believed Ross was reaching for a gun. Ross was not holding a weapon when he fell, and his family disputes he was armed. Lacey’s investigation said he was carrying a pink handgun in his pocket.

Bradford and others said Ross was well-known in the neighborhood and despite some describing him as acting strange at times, he was not viewed as a threat. He was “just kind of like a little kid in a grown man’s body,” said Ramirez, his sister — a guy who loved skateboarding, all kinds of music and his young son, Kenneth Ross III.

Imani Ross, Kenneth’s oldest sister, said that Kenneth was her first best friend — staying at their grandfather’s house at the edge of Rowley Park, the two would hang out there and play basketball.

“He was the best big brother I could have ever asked for,” she said Wednesday. “I will always be indebted to him for all that he’s done for me and for the love and joy he’s brought to my life.”

In the aftermath of Ross’ death, her whole family has changed, she said.

“No matter how happy I am, I still have a hole in my heart and I always feel like a piece of me is going to be gone,” she said. “The crazy thing is, I think for my mom it made her more loving and I think it made her more appreciative of everyone in her life. It made her stronger for sure. I just see a different side of her afterwards and it’s for the good.”

On Thursday, Almarou urged the crowd to chant Ross’s name after the bill was signed — a tribute to a boy she birthed when she was 18, and who died when he was just 25.

“I don’t need anyone saying anything bad about him in the press or the paper or something he did or didn’t,” she warned. “I am his mother. I was with him 25 years. He loved me. ... He didn’t deserve this. No family deserves this.”

She said she felt good seeing Newsom standing in Rowley Park, in honor of her son, and she thinks Bradford was instrumental in that too. That promise he made back in 2019 turned out to mean something.

“He came through,” she said. “He did what he said he was going to do.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.