A ‘thirsty’ atmosphere is propelling Northern California’s drought into the record books

- Share via

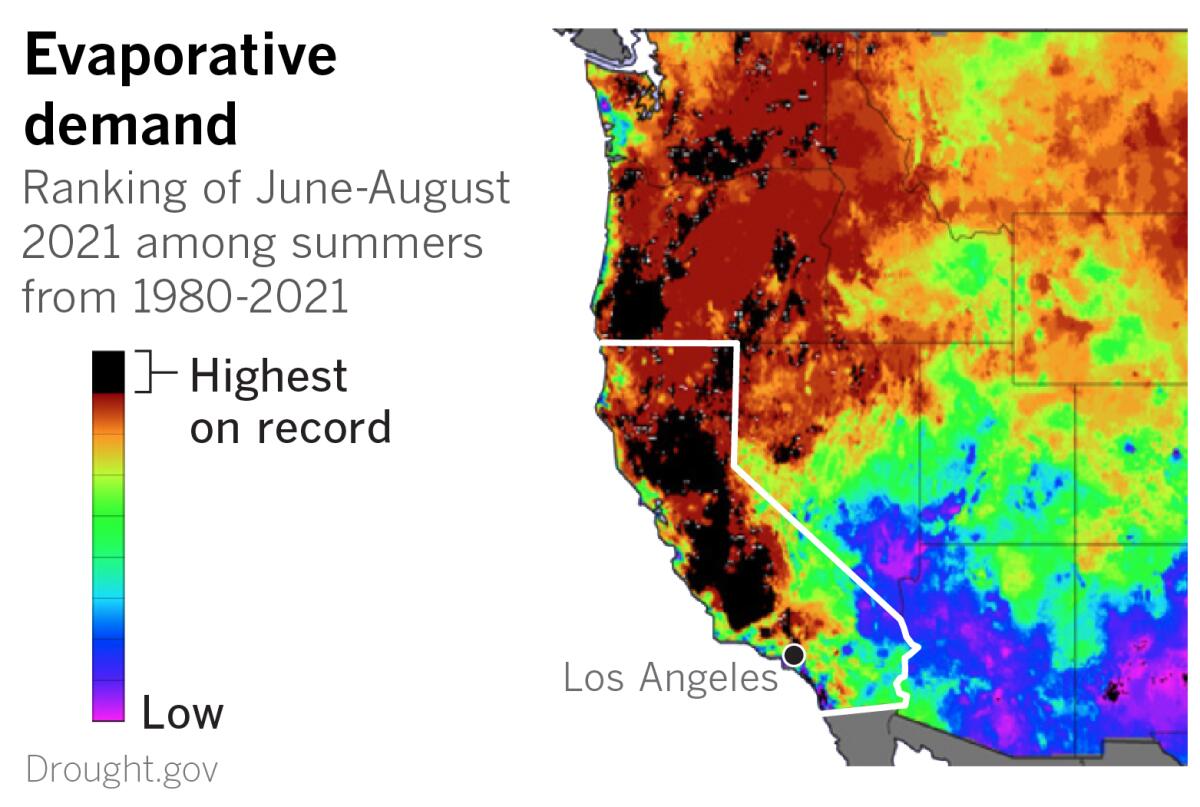

Increasing evaporative demand is escalating summertime drought severity in California and the West, according to climate researchers.

Evaporative demand is essentially the atmosphere’s “thirst.” It is calculated based on temperature, humidity, wind speed and solar radiation. It’s the sum of evaporation and transpiration from plants, and it’s driven by warmer global temperatures, which can be attributed to climate change.

The meteorological summer of 2021 in the contiguous United States, which runs from June through August, tied the extreme heat of the Dust Bowl summer in 1936.

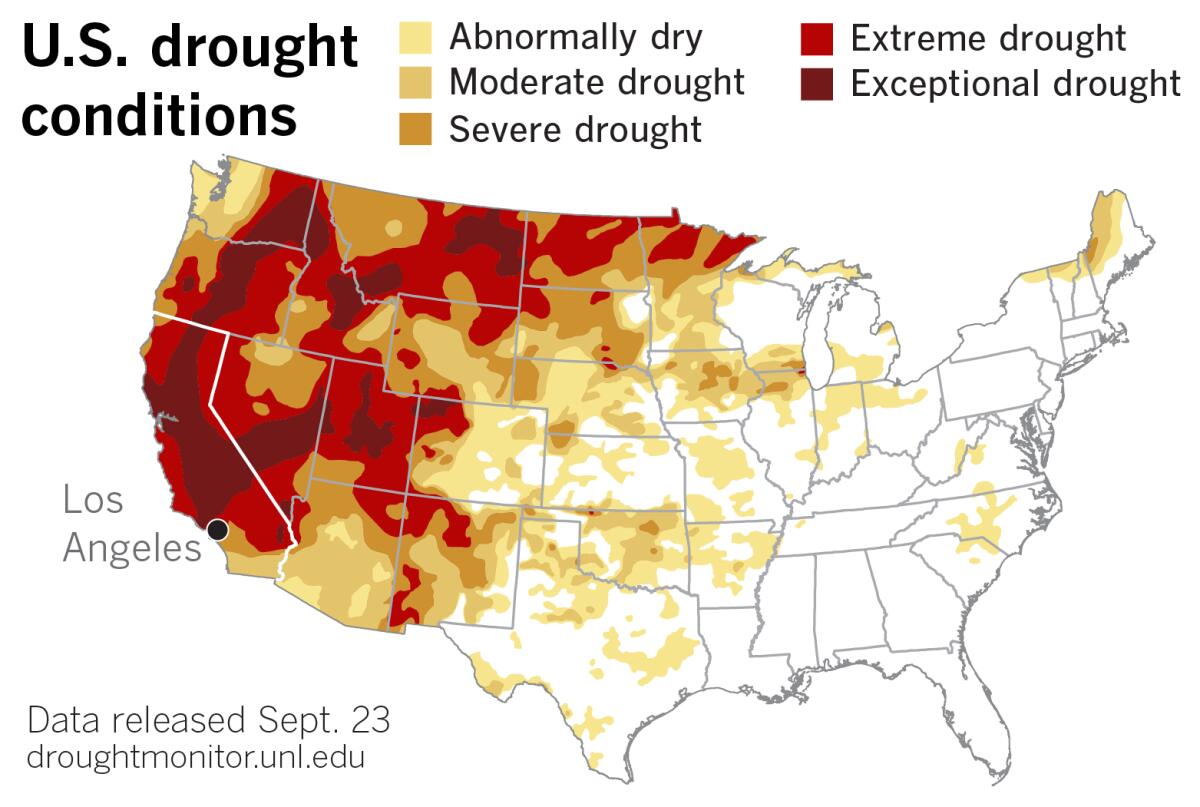

Evaporative demand has propelled almost half of California into what the U.S. Drought Monitor calls “exceptional drought.” It causes faster drying soils and vegetation, making fuels more dangerously combustible during the summer and fall, the peak of California’s fire season. As a result, fuels burn faster and hotter.

California and the West have seen a substantial increase in evaporative demand over the last half-century, worsening summer drought severity, said John Abatzoglou, an associate professor and climate scientist at UC Merced.

The drought in California isn’t just the result of a scarcity of precipitation. It is a combination of two things: a lack of rain and those thirsty atmospheric conditions that desiccate the landscape. For much of California, the 2021 summer and water year have had the highest evaporative demand in the last 40 years, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System.

As Abatzoglou points out, Northern California has endured the third-driest water year on record along with the highest recorded evaporative demand — factors that “place this year in a class by itself.” These things are remarkable, he adds, “given that the California drought hall of infamy is notorious.”

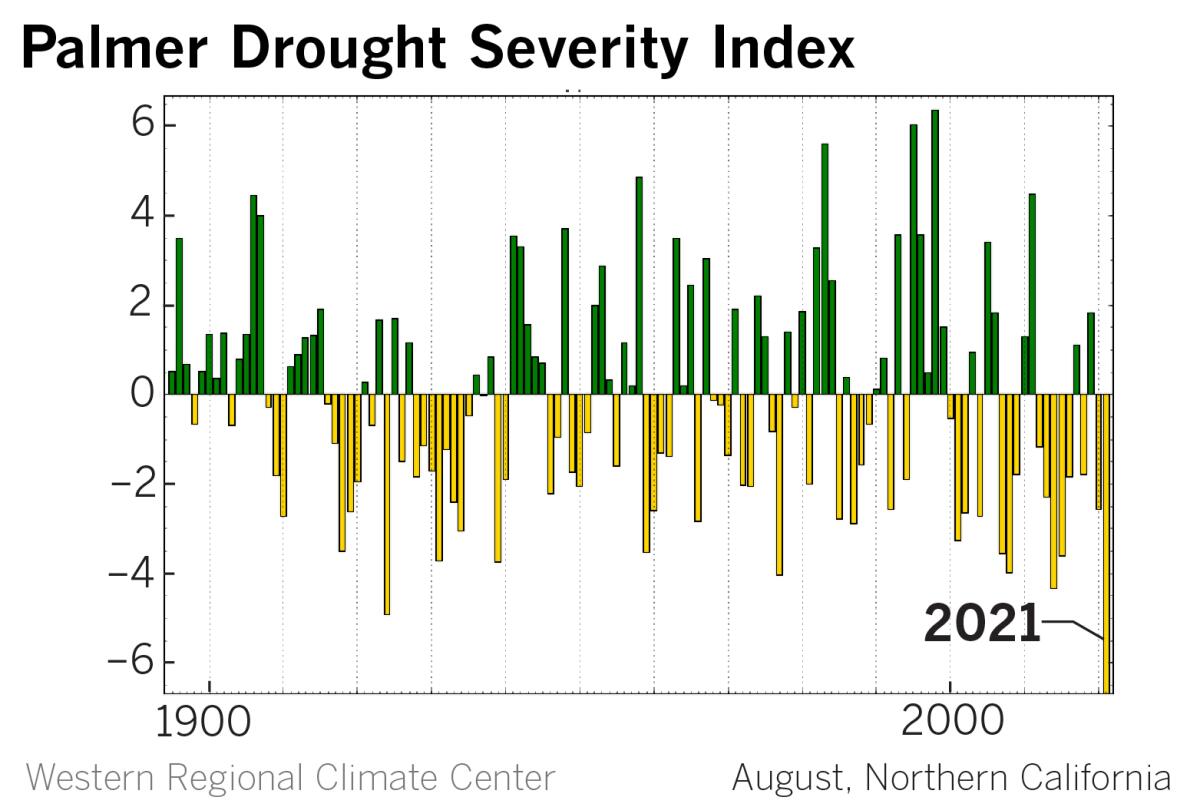

Abatzoglou cites the Palmer Drought Severity Index, which he describes as a general catch-all drought index widely used in the U.S., and part of what informs the U.S. Drought Monitor. According to that yardstick, Northern California is having its worst year in the instrumental record. The PDSI is a soil moisture index that accounts for both precipitation and evaporative demand.

Abatzoglou sees the “demand” side of the drought as something we’re beginning to appreciate. He says there have been dry droughts and then there have been hot and dry droughts. The latter have promoted increased summertime irrigation demands by agriculture in the Central Valley, energy imbalances due to higher demand caused by heat and reduced energy supply due to the reduction in hydroelectric power generation.

The latest U.S. Drought Monitor report, released Thursday, paints a dire picture of the situation in California and much of the West — as it has for months. In the current data, about 46% of the state is categorized as being in exceptional drought, while just over 42% is in extreme drought. The remaining approximately 12% of the state is about evenly divided between moderate and severe drought — meaning that 100% of the state is stricken by some level of drought.

Increased evaporative demand has exacerbated the dryness in vegetation that has enabled more wildfires this year. Active wildfires such as the Windy fire and the KNP Complex fires were among those that continued to consume parched vegetation in California.

The areas of exceptional and extreme drought in the Drought Monitor map track fairly closely with the pattern where evaporative demand in the state — that measure of a thirsty atmosphere — ranks as the highest on record for June through August. This oxblood-colored part of the map indicates the biggest departures from normal from California summers from 1980 to 2021.

In November, Science Daily quoted Abatzoglou as saying: “Increased evaporative demand with warming enables fuels to be drier for longer periods. This is a recipe for more active fire seasons.”

That prediction has been borne out in the summer of 2021.

Furthermore, in an April 2020 paper in the journal Science, on which Abatzoglou was one of the authors, the massive, continuing drought afflicting the U.S. Southwest was estimated to be 46% more acute because of human-caused climate change.

Another study a few years ago, by Abatzoglou and others, estimated that the 2012-2014 drought in California was 8% to 27% more severe because of a warming climate.

There have always been cyclical droughts in California and the West, but scientific evidence indicates that human-caused climate change is creating a warmer, thirstier atmosphere that sucks the moisture out of the landscape.

“The increase in evaporative demand is akin to putting an additional straw in one’s drink,” Abatzoglou said. “It is now that much easier to drain the cup.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.