The young Marines wanted to help. They were the last Americans to die in the Afghanistan war

- Share via

Shana Chappell scrolls through her smartphone, looking and looking for a video of her son, Kareem Nikoui. The one where he’s entertaining the little Afghan girl, taking her mind off the chaos that surrounds them at the Kabul airport.

There’s a metal bucket on the porch of Chappell’s Norco home half-filled with cigarette butts. Her voice is raspy, her eyes flat with fatigue. Finally, she finds it, near the message she sent him, “I need to hear from you.”

She presses play. Holds out the phone. A brown-haired girl in a pink shirt and jeans smiles at the camera. A friendly voice rings out: “Say ‘hi’ to the camera. Say ‘hi.’ Wave.”

“That’s his voice,” she says, then she goes silent.

Chappell has not slept for three days, not since she found out that her boy — the Marine corporal with the big heart, who loved jujitsu and boxing and going on the swings at a nearby park with his little brother Steven — was killed in the suicide bombing at Hamid Karzai International Airport on Aug. 26. He was 20 years old.

Nikoui was one of 13 U.S. troops who perished in the blast while helping frantic families leave their war-torn country. One of four Marines from California whose bodies in flag-draped caskets are making their way back home. To Norco and Indio and Roseville and Rancho Cucamonga.

Their families and their communities want you to know who they are: Nikoui and Sgt. Nicole Gee, 23, and Lance Cpl. Dylan Merola, 20, and Cpl. Hunter Lopez, 22.

They want you to know that Nikoui talked about enlisting in the Marines since he was a little boy. That Lopez wanted to join the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department, just like his mom and dad. That Gee didn’t enlist until she’d graduated high school and eloped with her boyfriend. That Merola didn’t have his driver’s license yet.

They want you to remember.

::

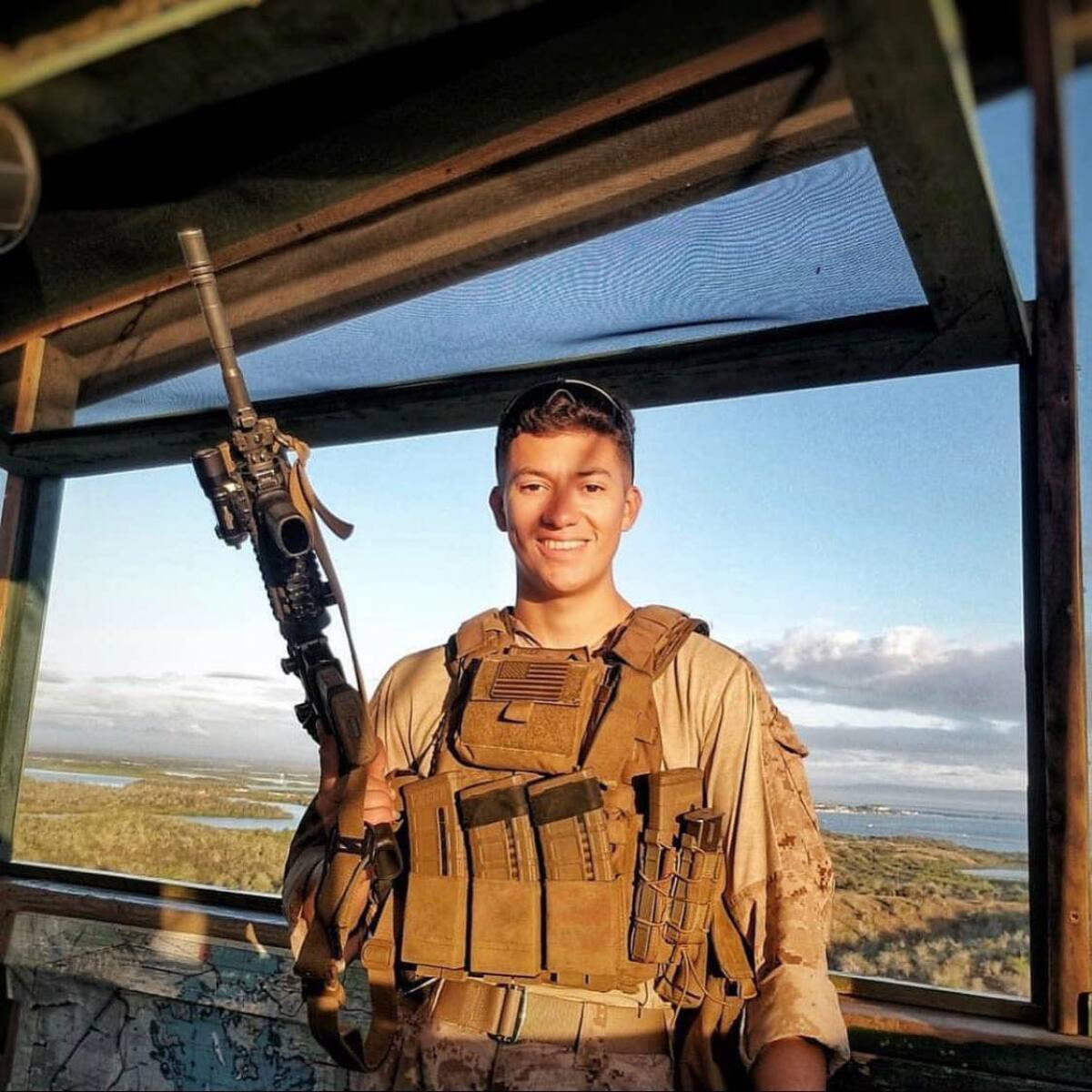

Kareem M. Nikoui

This is Chappell’s favorite story about her son, the fourth of her five children: Every Friday, when Nikoui was stationed at Camp Pendleton, Chappell would drive the 80 or so miles to pick him up and bring him home for the weekend — to the same house that now is festooned with black ribbons and U.S. flags. Every Sunday she would drive him back.

When she returned from Pendleton after dropping him off on her birthday in 2020, she found a note on her pillow.

“He said he was sorry he hadn’t bought me anything for my birthday,” Chappell recounts, “but money was tight for him at the moment.”

He said he loved her. He said he wouldn’t want any other mom in the world.

This July, when Chappell’s birthday rolled around, Nikoui was in Kabul. But presents from her son began arriving the day before and continued on until the celebration was long over. Slippers and shoes. Soaps and lotions. Paintings he’d commissioned of her dogs, Niko, Komodo and King.

“This birthday, he had money to spend,” she says. “He just wanted to do something nice for his mom.”

Chappell has just gotten back from Dover Air Force Base, where she watched caskets carried gently off a C-17 cargo plane. And where she met with Joseph Biden, the man she will not call president.

She told him that she didn’t want to talk to him but that she was doing so out of respect for her dead son. She told him she was never going to get to hug her son again. She told him that it was his fault.

“My son’s blood,” she told him, “is on your hands.”

Nicole L. Gee

Tuesday night. Roseville town square. Hundreds gathered under golden evening sunlight at a vigil for the self-driven sergeant with a bright smile and dreams of starting a family.

Local law enforcement agents and U.S. military personnel, plainclothed and uniformed, young and old, surrounded Gee’s family — her high school sweetheart turned fellow Marine and husband, Jarod Gee, 24; her sister, Misty Fuoco, 26; and her father, Richard Herrera, 56.

Gee was en route to Afghanistan on Aug. 14. Six days before the fatal explosion, she posted a photo of herself on Instagram, cradling an Afghan baby. Her caption: “I love my job.”

That patriotism and love of service were part of the crowd’s common language. When Roseville Mayor Krista Bernasconi, a veteran of the U.S. Navy, asked the other veterans to stand, they rose as one, a sea of waving arms and flags.

“She was one pretty badass Marine,” Gee’s sister said, standing at the lectern, an enormous flag taut behind her. She remembered Gee’s angst over losing 12 pounds of muscle at boot camp, where she couldn’t get enough workouts in. “But Nicole was so much more than that,” Fuoco said.

She had a competitive spirit, was a natural listener, excelled at everything she tried, her family said. She graduated high school with a 4.1 GPA and could deadlift 280 pounds, more than twice her body weight. She pushed herself and encouraged others — helping her younger brother Thor with his homework and cheering her friend and fellow Marine Erin Libolt through tough workouts.

When Herrera took the stage Tuesday evening, his voice wavered.

“I can’t believe that little girl’s got all these people together,” he said, looking out into the crowd. Jarod Gee’s knee bounced as he listened to a story about his late wife as a child, fearlessly dominating the slopes the first time her family went snowboarding.

Herrera didn’t speak for long.

“The world’s watching Roseville,” he said to the crowd, taking a deep breath, “so do what’s right.”

He shuffled the pages on the lectern before him. Paused, as if about to begin again. Sighed heavily and turned away from the microphone. When he finally faced the crowd again, he could not find more words to say.

Except, “God bless you, Nicole.”

And, “Never forget her, please. Never forget her.”

Dylan R. Merola

Near Beryl Park in Rancho Cucamonga, 13 flags hang on a freeway overpass, alongside red, white and blue balloons. There’s a folded flag resting beneath them and a white sign: “Remember The Fallen ... Semper Fi.”

Thirteen names are written in red, among them one of Rancho Cucamonga’s own, “LCPL Dylan Merola.”

Merola was a theater kid during his four years at Los Osos High, heavily involved in theater tech, helping with lighting, sound and props. He was the kind of student who’d always ask if someone, anyone, needed a hand.

“He was the one who would come early and stay late,” said Randy Shorts, the school’s theater director. “He always had that willingness to serve and to be helpful and just pitch in wherever he could.”

In every picture he has of Merola, Shorts said, the young man “has his big smile, just being goofy.”

There was the time Merola danced with a friend at a restaurant after a show. The time he posed on a pirate ship he had helped build, standing at the front like a scene from “Titanic,” his arms outstretched and a friend behind him.

“He was definitely the kind of kid who would just make you laugh,” Shorts said.

When everything feels too overwhelming, Shorts said, he looks at a photo of himself and Merola taken a couple of years ago during a surprise snowfall. Shorts’ class had gone outside for a snowball fight. Shorts and Merola are both grinning.

“That’s been my little therapy picture,” Shorts said, “the one I’ve really been sort of clinging to.”

Merola graduated in 2019. He planned to go to college after the Marine Corps and study engineering, said Dakota Mancuso. The friends met in technical theater class as sophomores.

They spoke for the final time just days before the bombing. Merola had been called out to Afghanistan from Jordan.

“He said he’d be evacuating the airport and that the situation wasn’t very good,” said Mancuso, 20. “He had a list he was calling ... to make sure he called everyone he knew before he left.”

Mancuso wanted to teach his friend how to drive. He wanted them to go out for a beer together, celebrate their 21st birthdays.

“We didn’t get to do any of those things together,” Mancuso said. “Twenty just isn’t that old.”

Hunter Lopez

Hunter Lopez found his passions early.

When he was 5 years old, the avid Star Wars fan named his brother Owen, after Luke Skywalker’s uncle, his mother said. He loved Disneyland because of the Star Wars ride. Herman and Alicia Lopez planned to take their son there when he got back from Afghanistan so they could all ride the newest attraction — Rise of the Resistance.

Together.

As a 3-year-old, he wore a tiny sheriff’s uniform to his mother’s graduation from the Sheriff’s Department academy. Alicia is a deputy with the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department, and Herman, a captain. The young Marine dreamed of joining the SWAT team in his parents’ department.

“He was going to follow in their footsteps,” said Jose Peralta, who became friends with Lopez during infantry training early in their careers as Marines.

They bonded over “Nacho Libre,” spouting the cult film’s most famous lines: “Did you not tell them they were the Lord’s chips?” “Get that corn outta my face!” They cracked jokes and helped fellow Marines get rifle qualified at Camp Pendleton.

Peralta was disappointed he didn’t end up in the same company as Lopez and another friend, Humberto Sanchez, ahead of their deployment to the Middle East. But they were able to reunite for a few hours in August while working in Kabul.

They swapped stories about the crowds and the people they had helped. They talked about how close they were to going home.

The next day, Lopez and Sanchez were on post at Abbey Gate at the Kabul airport. Peralta was at the airfield a few hundred meters away when he heard the explosion and saw smoke, dirt and debris kicked up into the air.

Peralta was one of eight Marines who carried Lopez’s casket onto the C-17 transport plane in Afghanistan for the flight out.

Waiting officers gave a final salute. The eight troops set the casket down inside the cavernous aircraft. As the chaplain prayed, they dropped to their knees. Cried. Held his casket one last time.

“That was probably the hardest thing I ever had to do,” Peralta said. “I never expected any of my friends to leave in caskets with flags draped over their bodies.”

Peralta, who is still in the Middle East, said he wants Sanchez and Lopez to be remembered and celebrated. In Camp Pendleton, there’s a mountain with crosses that bear the names of fallen Marines. Peralta said he plans to plant crosses there for his fallen friends.

Peralta told Lopez’s family that if he and his wife have a son, they plan to name him Hunter.

“I would hope that people would celebrate and remember them,” Peralta said.

That’s what he plans to do. For the rest of his life.

Estrin reported from Roseville, La Ganga from Norco and Mejia from Rancho Cucamonga.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.