Kevin Faulconer has the resume. But can a ‘vanilla’ Republican win the California recall race?

- Share via

For a guy known for his collegiality, Kevin Faulconer came out swinging at the last California recall debate.

Faulconer said conservative talk radio show host Larry Elder does not have “the character, the judgment, the skill set or the experience to be governor.”

Democrat Kevin Paffrath, a 29-year-old YouTuber who has never held elected office, would need “on-the-job training,” Faulconer said.

The former mayor of San Diego also fired a broadside at the rest of the candidates, as well as Gov. Gavin Newsom, telling voters: “We don’t want to replace one dysfunctional governor with another.”

The verbal jabs complement a long political pedigree. Faulconer is the most experienced politician heading into the Sept. 14 election, a Spanish-speaking Republican who spent six years running a city where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans 2 to 1. But Faulconer is still struggling to break out of a pack of 46 candidates that includes a reality show star, a 66-year-old who brought a 1,000-pound bear to a news conference and Elder, whose former fiancée accused him of checking to see whether his gun was loaded during an argument.

More liberal than the national Republican Party on abortion rights, gay marriage and climate change, Faulconer has long been considered the GOP’s best shot at winning statewide office after a 15-year drought. In a one-on-one matchup with Newsom, he’d have a great shot, his supporters say.

But it’s been hard for moderates like Faulconer to gain traction in this campaign driven by extremes. Faulconer harkens back to an earlier era of American politics, when the old joke was that candidates came in two flavors: Democratic vanilla and Republican French vanilla, “a little creamier and a little richer,” said Carl Luna, a professor of political science at San Diego Mesa College.

“Kevin is French vanilla,” Luna said. “But a lot of people don’t want vanilla. They want rocky road jalapeño with Tabasco sauce on top.”

For years, he built a brand as an affable, across-the-aisle kind of guy in California’s second-largest city. A political insider once warned that profiling Faulconer would be like “investigating dry white toast.” (Asked if he’s boring, Faulconer said, “Oh, I think I’m pretty funny.”)

The self-described “vanilla” candidate is now walking a political tightrope: Reach out to independents and Democrats hunting for a palatable alternative to Newsom, while mollifying Republicans who doubt his conservative bona fides.

He’s going hard after Elder, demanding that the talk-show host drop out of the race over his attitude toward women, including past comments that they “know less than men” about politics and current events. That, Faulconer said, is “bullshit, and we ought to call it that.”

He’s appealing to working parents, proposing to implement fully paid parental leave for primary caregivers for up to 12 weeks. He’s also proposed 200,000 more spots in state-funded childcare and an elimination of state income tax for families that earn less than $100,000, which would require legislative approval.

And he’s hammering Newsom for his handling of the pandemic. Schools should have been open in the spring, Faulconer says, and masks and vaccinations shouldn’t be state-mandated. He told The Times he would not renew a ban on evictions set to expire Sept. 30.

“This is a time for seriousness,” Faulconer said. “... If you want to replace an existing governor, you’d better tell people what you’re going to do and how you’re going to govern.”

Faulconer, 54, grew up in Oxnard and graduated from San Diego State. Before he entered politics, he worked in public relations, including as a vice president at Porter Novelli. He’s married with two children.

Unlike other recall candidates, his supporters say, Faulconer actually has a track record to scrutinize. San Diego voters elected him to the City Council, then to the mayor’s office, after a scandal called Strippergate and a spate of sexual misconduct allegations forced out his Democrat predecessors.

Faulconer has touted his record paving roads, reducing homelessness, backing a plan to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and increasing police funding as other California cities did the opposite. He helped scuttle a proposed 2010 sales tax increase and championed pension cuts after the early-2000s financial crisis that earned San Diego the nickname “Enron-by-the-Sea.”

His critics say he had few ambitious proposals and several major failures, including the fatal hepatitis A crisis and the departure of the city’s NFL team to Los Angeles. Drawing on his experience in public relations, Faulconer tended to govern based on optics, they said, spurred to action only by a bad headline or a looming crisis.

“Kevin wants to be the moderate,” said former Mayor Bob Filner, who resigned in 2013 amid repeated claims of sexual misconduct and was replaced by Faulconer. “Whatever the extremes are, he’s going to be in the middle. It doesn’t matter if one side is right and one is wrong, or both are wrong — he’s going to be in the middle.”

Like so much about the recall, Faulconer’s accomplishments are more complicated than they appear. The progress against homelessness was bolstered by a change in methodology. His push to tackle pension costs ended in defeat when a court struck down a voter-approved ballot measure. And some of his local dealings raised eyebrows, including five real estate deals that cost more than $230 million.

One of the worst crises during Faulconer’s tenure, the 2017 outbreak of hepatitis A , thrust the city’s historical failures on homelessness into the national spotlight and pushed him into action. The epidemic of the liver-damaging disease, which is spread through fecal matter, killed 20 people, most of them homeless, and sickened almost 600.

The city shifted $6.5 million from a permanent housing budget to pay for 700 beds in three new tent shelters, then gave homeless people the choice between going to a shelter or facing arrest or citation.

Later in Faulconer’s tenure, the city created a diversion program that allowed homeless residents to avoid prosecution and fines if they stayed in a shelter for 30 days. He also used the convention center as emergency housing for the homeless during the pandemic.

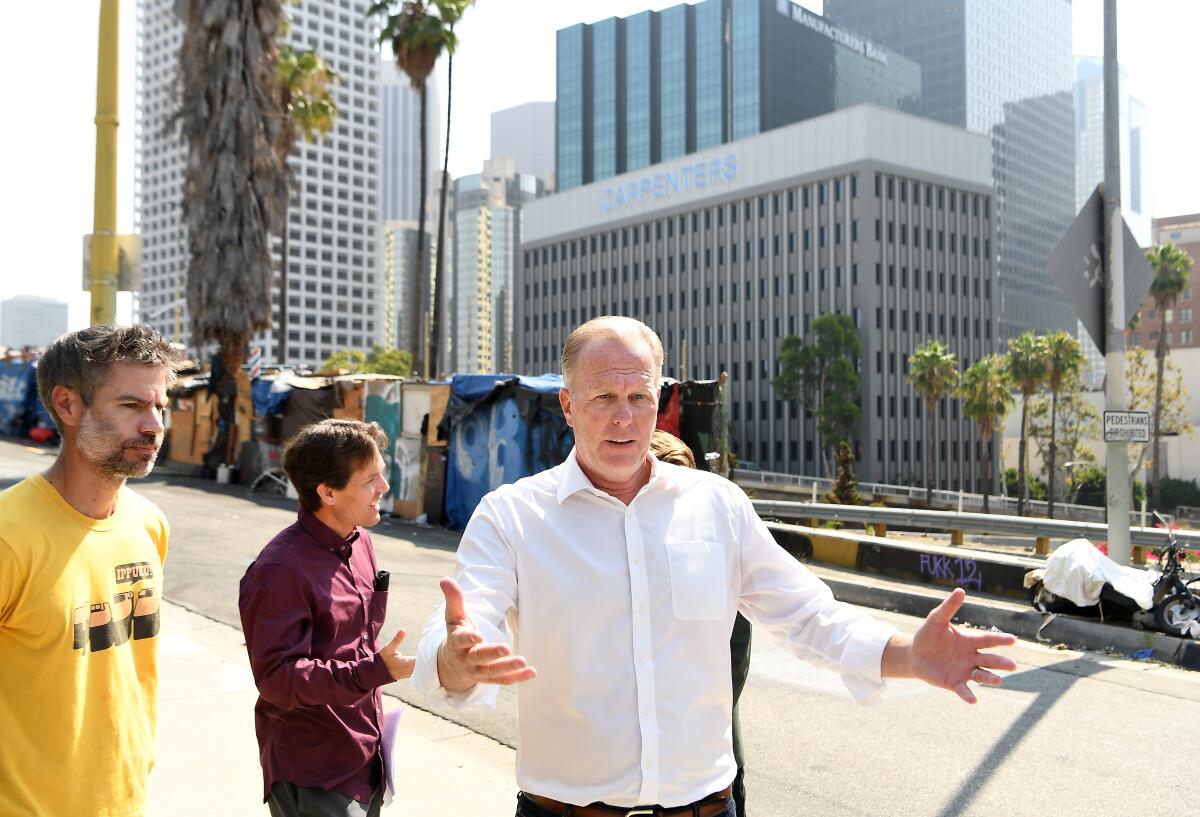

If he were governor, California would replicate that model, building far more shelters and using “compassionate but effective” police enforcement to push homeless people into accepting help, Faulconer said. Cleaning up sprawling encampments in places such as Venice Beach and Echo Park wouldn’t have to happen, he said, because he wouldn’t allow people to sleep on the street.

“You have to let folks know that it’s not OK ... to live on a sidewalk in front of somebody’s house or in front of somebody’s business if we have provided a safe, clean, sanitary place for you to go,” Faulconer said. “... I don’t want people to die on our sidewalks. If you allow somebody to live in a tent on our sidewalks, they’re gonna die there. We’re better than that.”

Faulconer frequently says, and advocates dispute, that San Diego reduced homelessness by “double digits” as the crisis spiked in other parts of the state. The number of homeless people sleeping outside in the city fell 12% from 2019 to 2020, according to regional homeless counts. The city’s overall decline was about 4%,

It’s an “overstatement” to say that Faulconer’s actions reduced homelessness, said John Brady, a homeless advocate who serves on the task force that produced the data. He said that police officers had temporarily pushed homeless people into jail, shelters and outlying areas before the data were collected, and a change in the counting methodology excluded people living in vehicles.

Faulconer made national headlines in 2015 when he adopted an aggressive climate action plan to slash carbon emissions, making a legal commitment to use 100% renewable energy by 2035.

He also backed density along transit corridors and proposed some of the state’s most aggressive strategies to promote multi-unit new construction. In his 2019 State of the City speech, he said: “We must change from a city that shouts ‘Not in My Backyard!’ to one that proclaims ‘Yes in My Backyard!”

In the Aug. 5 debate, he said he would veto any bill that would eliminate single-family zoning, calling the proposals “wrong.” He also told The Times he would pull the plug on California’s “boondoggle” bullet-train project.

The state’s beleaguered unemployment system, with long wait times and billions of dollars in fraudulent claims that Faulconer said were “unconscionable,” could use the same treatment as San Diego’s troubled 911 dispatching system, he said. Faulconer brought in new leaders, gave 911 dispatchers raises and found ways to reduce burdens on the system, including creating a 311-esque mobile app to reduce the burden of non-emergency calls.

He also helped to reform San Diego’s pension system in the “hangover” that followed the pension crisis, said Jason Cabel Roe, Faulconer’s former campaign strategist. Deals between the city and its unions in 1996 and 2002 to underfund the retirement system in return for increased benefits contributed to huge deficits, which continue to rise.

Faulconer helped stabilize the city’s finances, Roe said, and took aim at ballooning pension debt by co-authoring a ballot measure that gave new hires, except police officers, 401(k)-style plans instead of pensions. The measure won wide support from voters but sparked a nearly nine-year legal battle with organized labor.

The California Supreme Court later found that the measure had been placed on the ballot illegally because the city had not negotiated the terms with the unions. The city is now preparing to start awarding pensions to new hires, and studying how to compensate the roughly 5,400 workers who received 401(k)-style plans instead.

Faulconer also faced local frustration over a series of troubled real estate deals. In one case, he directed the city to approve a lease-to-own deal for a downtown office tower. The city later found asbestos there and is now facing dozens of claims over exposure. The high-rise, at 101 Ash St., is vacant.

“When you’re mayor, not every project is going to go well,” Faulconer said. He said he “took a stand” by suspending the $535,000 monthly payments last September and called for an independent review.

A July audit found that Faulconer’s administration had omitted or misrepresented key facts. The mayor’s office also relied on a real estate advisor who had “significant influence” and who received $9.4 million from the company leasing two of the buildings, auditors said.

“That is absolutely, 100% on him,” said former City Councilman David Alvarez, who lost the 2014 mayor’s race to Faulconer. “The city could have used the money for so many other things.”

As the Republican mayor of a border city who had worked to build ties with Mexico, Faulconer walked a delicate line with former President Trump, mostly trying to avoid him.

In 2019, the president heard Faulconer was inside the White House and invited him to the Oval Office for a surprise meeting and a photo op. The next night, Trump told Sean Hannity on Fox News that Faulconer had come to his office “to thank me for having done the wall because it’s made such a difference.”

Faulconer’s spokesman swatted down that description, saying: “We all know that the president uses his own terminology.”

In 2016, Faulconer declined to endorse Trump, saying that his “divisive rhetoric is unacceptable” and that he “just could never support him.”

In 2020, Faulconer voted for Trump, saying that “it was a very clear choice this last election, particularly on the issue of the economy.” Faulconer has repeatedly refused to say whether he would vote for Trump in 2024 were he the Republican nominee.

Asked whether he saw cognitive dissonance between his 2016 and 2020 positions, Faulconer leaned on his vanilla strategy: Like any voter, he said, he had made his decision “on the facts of the time.”

Times staff writers Seema Mehta, Melody Gutierrez and Julia Wick contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.