Column: He’s kept a radio vigil for Vicente Fernández for two decades

- Share via

Wearing a tie and a long-sleeve shirt, with a microphone in front of him, a notepad on his desk and a book of dream interpretations by his side, Rubén Miranda looked like a therapist as he readied to take phone calls for an hour last week in the Burbank studios of La Ranchera 96.7 FM.

First up was Ruben from South Gate.

“Buenos días — hola, Rubencito,” Miranda said in his rapid-fire, sonorous voice. “How are we doing?”

“Really sad.”

“Why?”

“Por mi Chente,” Ruben responded in agony. For my Chente.

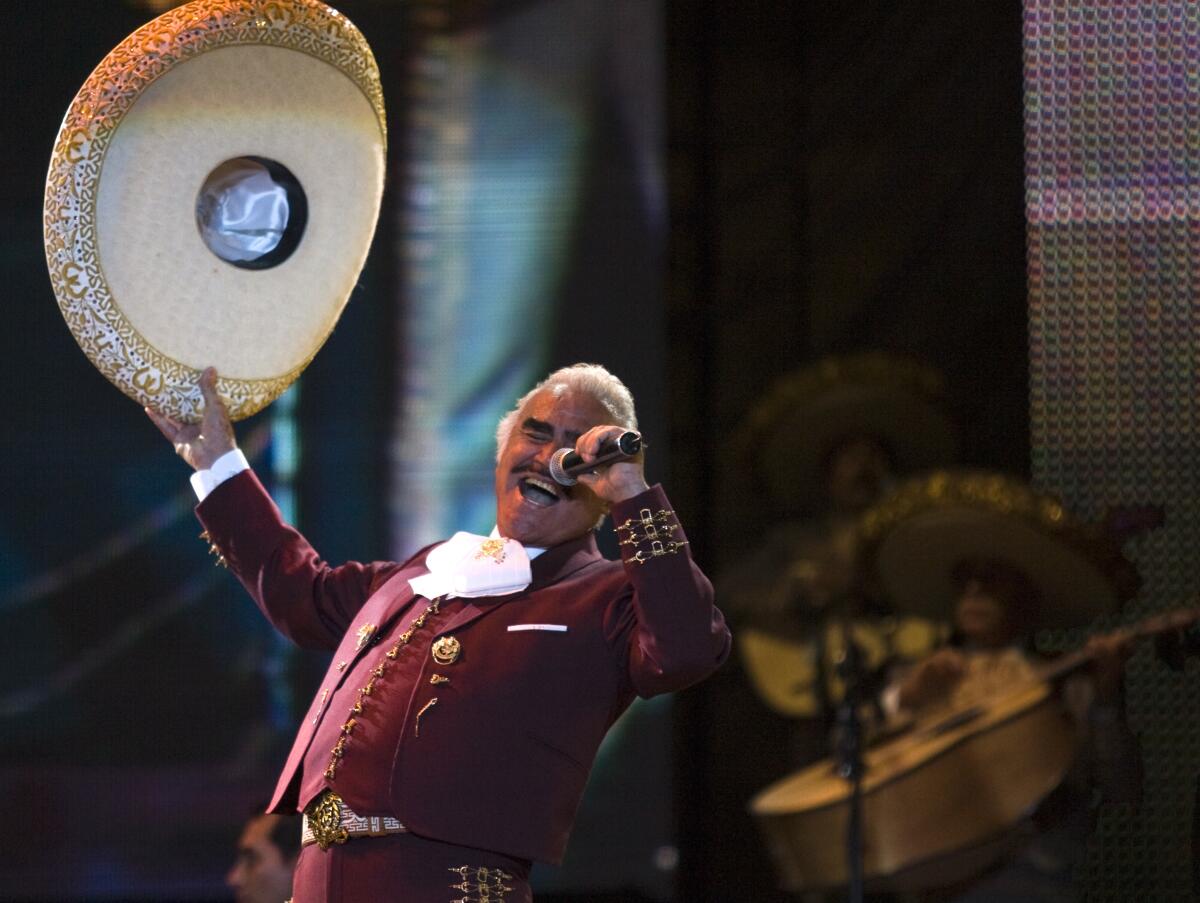

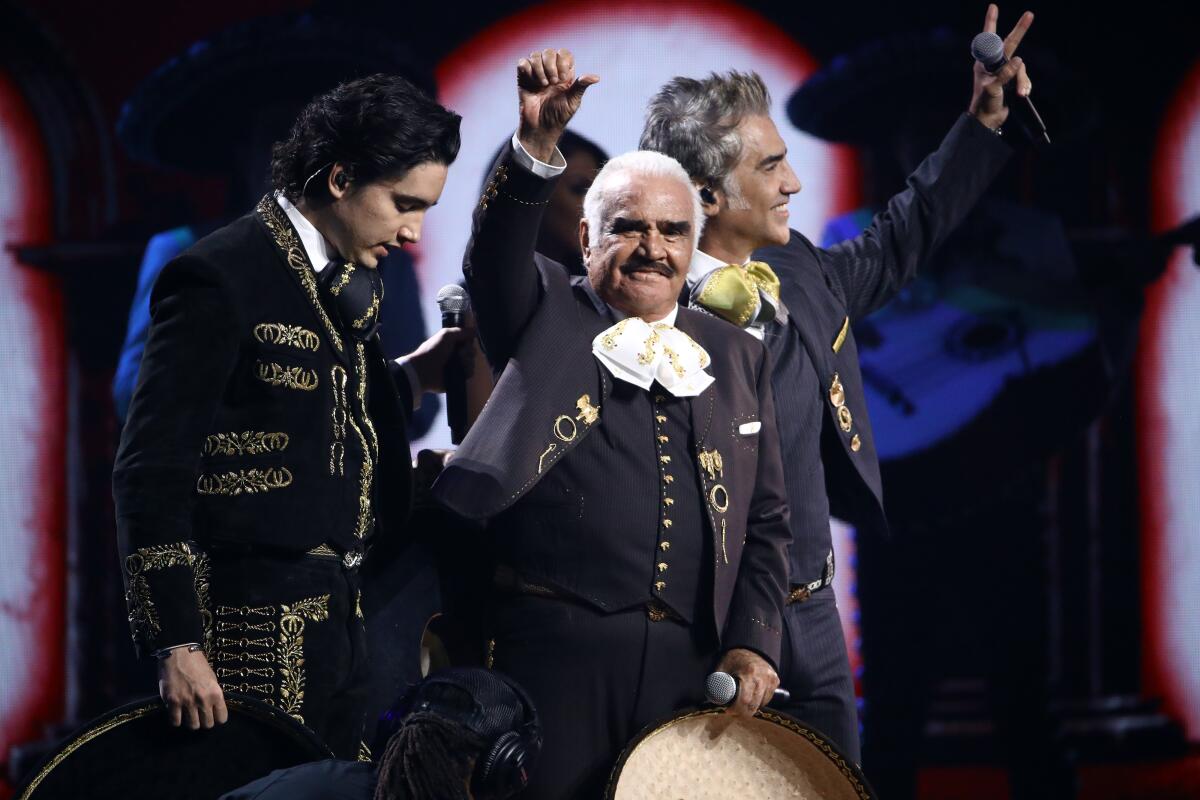

Four days earlier, on Aug. 8, Mexican music legend Vicente “Chente” Fernández took a fall at his ranch in Huentintán in the Mexican state of Jalisco and injured his cervical spine. Almost immediately, the English- and Spanish-language press across the Americas freshened up their prewritten obituaries of the 81-year-old ranchera singer, while fans held online vigils worldwide.

The news hit Miranda hard. Nearly every weekday for the last two decades, the Mexican immigrant has hosted a five-hour radio show on La Ranchera, which specializes in the Mexican version of oldies-but-goodies: corridos, boleros, norteñas, trios and duets but especially rancheras — ballads of love and the rural life that old and young Mexicans still sing and listen to on both sides of the border decades after their release.

Miranda usually spends his time taking requests from listeners, with whom he playfully banters in Mexican slang from all regions of the country. His taglines — “Rubén Miranda, donde usted manda” (“Rubén Miranda, where you command”) and “Mami, me voy a casa” (“Mommy, I’m going home”) are classics of Los Angeles Spanish-language radio lingo.

But his bosses also task Miranda to host the one-hour “El Rancho de Vicente,” a noontime show that’s La Ranchera’s most popular program and is wholly dedicated to the songs of Fernández, which have served as part of the soundtrack of Mexican American life for nearly 50 years.

The show is so important to the station that Fernández is part of their logo, a Mount Rushmore of ranchera that also includes matinee idol Pedro Infante and singer-songwriter José Alfredo Jiménez. It’s splayed across Southern California billboards, bus benches, and posters. So as the world awaited news of Fernández’s health, Miranda knew he had to play his part:

Let the faithful fret, and pray alongside with them.

“Let’s hope he gets better fast,” Miranda calmly quickly told Ruben, as he cued up the caller’s request, “Mujeres Divinas” (“Divine Women”) on La Ranchera’s computerized playlist . “We’ll play your song soon, little buddy.”

Next up was Elsie, a Guatemalan immigrant. “I’m just here really sad, but loyal to the cause,” she said before asking for “Con Golpes de Pecho” (“With Blows to the Chest”). “May our idol get better, so help us God.”

“Right on,” Miranda said. “We’ll continue to support the last idol.”

For the entire hour, the calls didn’t stop. Alfredo from Carson. Eva Luz from Santa Ana. Roberto from the Dominican Republic, who said that while he wasn’t Mexican, he loved Fernández’s music because “his lyrics are universal.”

Miranda took notes, read ads, and tried to reassure his audience to not lose hope.

“We all hope that el buen Chente gets better,” he said. “Let’s just ask Diosito that it happens.”

Fernández still remains in a Guadalajara hospital, on a respirator but alert. And Miranda continues his watch on “El Rancho de Vicente,” which has been a hit for La Ranchera ever since Miranda inaugurated it in November 2000.

Copycat shows have sprung up across the United States. Other stations mimicked the format to do their own programs dedicated to other Mexican musical legends like Chalino Sanchez, Los Bukis and Antonio Aguilar.

“We Mexicans, when we fall in love with something, we don’t let it go,” said La Ranchera programming director Ernesto Morales, 48. He sets the playlist every day, but lets Miranda tinker with it as needed “because he’s a maestro at this. I’m just here to help.”

The success of “El Rancho de Vicente” is about more than just the music, said Adrian Félix, a UC Riverside ethnic studies professor who’s a fan of the show and other similar programs. “They create a community, an oral public space. It seems like such an old school technology for the younger generation, but it’s still a powerful medium.”

Slight, skinny and silver-haired, Miranda is naturally chipper and feels that Fernández — who has survived other health scares in recent years such as prostate cancer, pulmonary thrombosis and a urinary tract infection — will pull through.

“He’s the charro who puts on his boots on real tight,” he said with a smile.

But then he tried to imagine a world without Chente.

“If the people are already worried,” he added quietly, “it’s going to be one huge blow when he finally dies.”

Miranda started in radio as a teenager in 1967, the year that Fernández recorded his first album. The Chihuahua native went on to became a television host in Guadalajara in 1972, when the forlorn “Volver, Volver” became Fernández’s first smash.

“I remember walking through the city that year,” Miranda said. “Every bar was playing that song. Chente was basically born an idol — God gave him a little kick of luck.”

He moved to the United States in 1986 to work at Radio KALI, one of the earliest Spanish-language radio stations in Southern California, before helping to launch La Ranchera in 1998 as a host and programmer. Two years later, he was tasked with heading “El Rancho de Vicente” after the station’s bosses realized how popular Fernández was in the United States.

“He’s bigger here than in Mexico,” said Pepe Garza, a longtime kingmaker in Southern California’s Mexican regional music scene who’s a creative executive for Estrella Media, the parent company of La Ranchera. He remembers moving to L.A. in 1998 and “being surprised” at this seeming anomaly. “In Mexico, he was a mythical personality but his music wasn’t really played. Here, he was at the level of Pedro [Infante].”

Fernández’s stateside popularity is easy to understand, said Morales. “Well, the songs, of course. The voice. But when we play Chente, the older people remember life back in Mexico. And younger people remember when they were children and their parents played his music.”

“Other artists are popular, but they just don’t have that cachet,” added Miranda. “He’s urban and country, regal and down-to-earth like no one else. And people just put him on a pedestal like none other.”

Miranda had interviewed Fernández a few times before the show’s debut, when Chente showed up to La Ranchera’s studios to offer a blessing. For an hour and a half, Fernández regaled listeners with stories of his early days opening for Jiménez at the Million Dollar Theater in downtown Los Angeles and took calls. And he expressed his gratitude to La Ranchera.

“In Mexico, there’s many radio shows dedicated to me, but this here program is a very important new event for me,” he told Miranda.

Fernández never again appeared on “El Rancho de Vicente.”

“He’s buena onda,” Miranda said, using Mexican slang for “cool.”

The show has only gotten more Chente over the years. Morales originally played covers of Fernández songs until listeners complained that “they weren’t as good as how Chente sang them.” Every Feb. 17, La Ranchera plays Fernández’s canon all day. There are occasional giveaways — special collector CDs and DVDs, trips to Fernández’s hacienda Los Tres Portillos as a lover’s retreat — but Morales and Miranda don’t plan to tinker with the program much more.

One thing that isn’t in question is the show’s future, regardless of Fernández’s health.

“He’s like the Beatles,” Morales said as Miranda played “Adiós Mariquita Linda” (Goodbye, Beautiful Mariquita”), the last song of the hour for the day. “Chente is never going away.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.