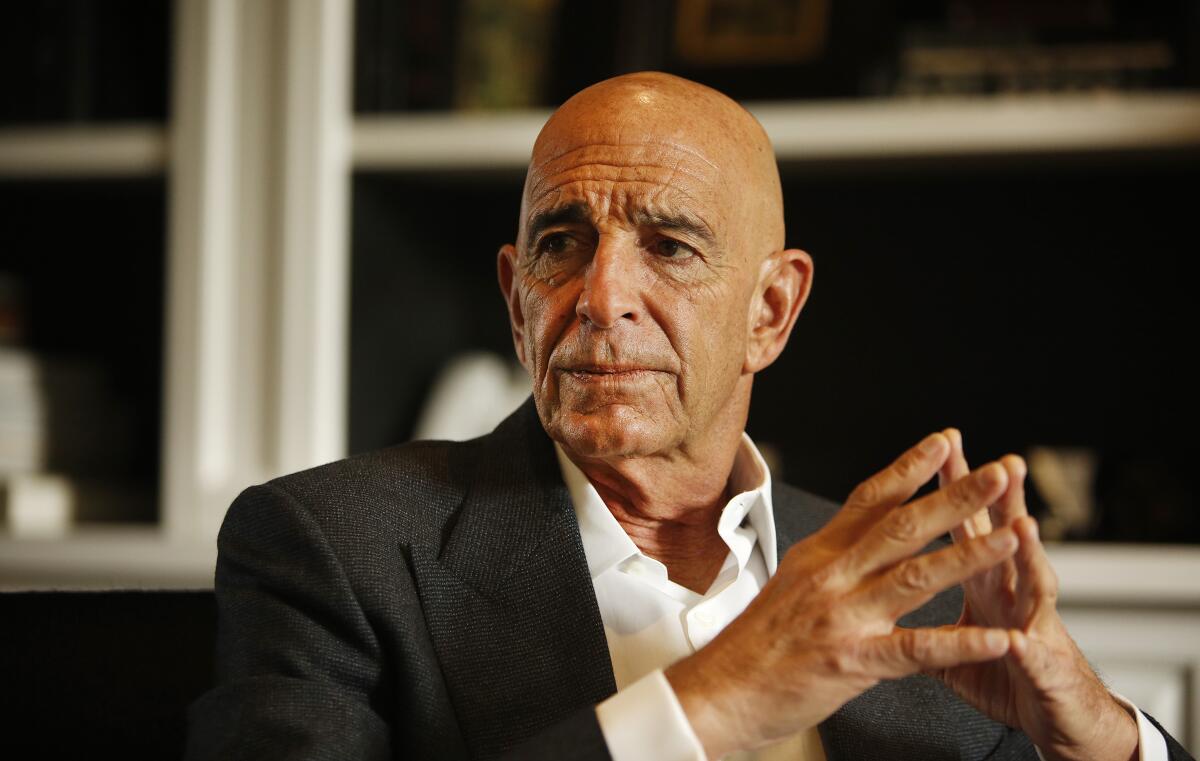

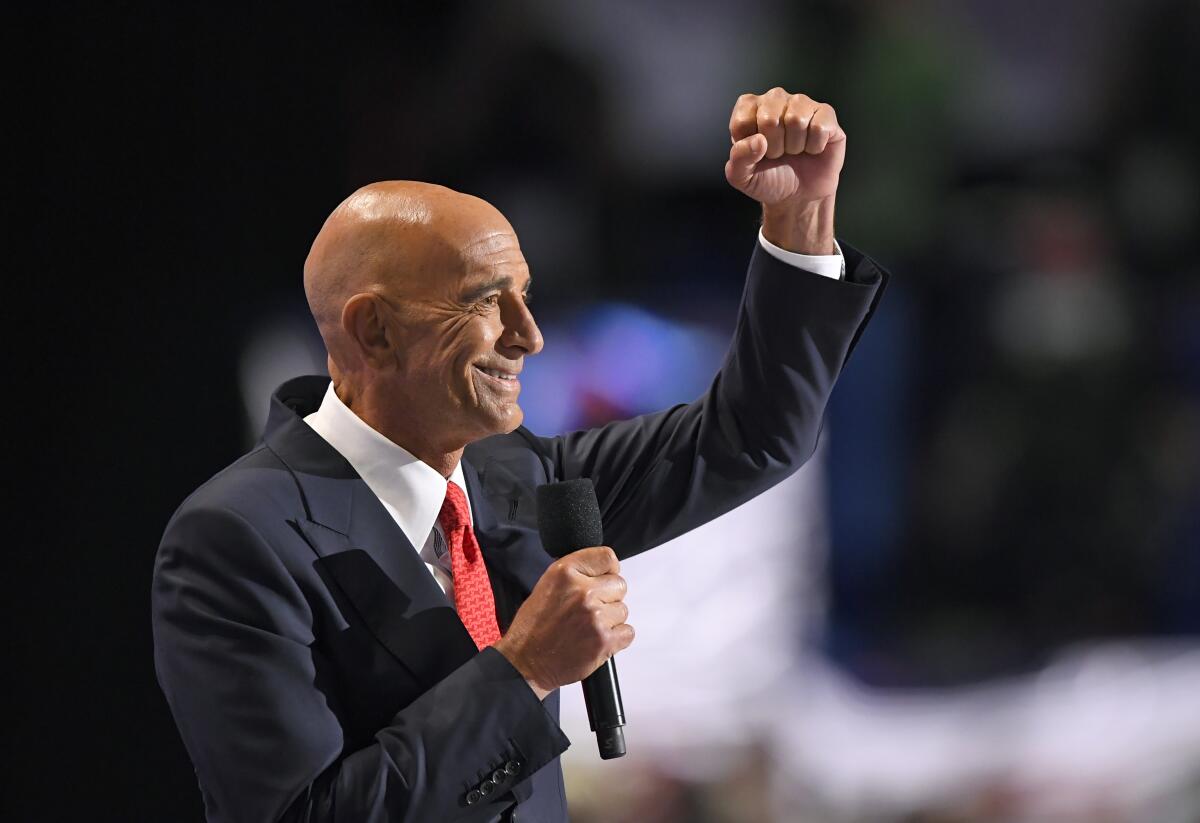

Trump ally Thomas J. Barrack Jr. released on $250-million bail

- Share via

Thomas J. Barrack Jr., a prominent Los Angeles investor and longtime ally of former President Trump, was released from jail Friday on a $250-million bond while he awaits trial on charges of covertly acting as an agent of the United Arab Emirates, obstructing justice and lying to the FBI about his work.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Patricia Donahue ordered Barrack’s release after the wealthy real estate developer agreed to put up the huge sum as a guarantee he would not flee the country to avoid prosecution.

Barrack provided $5 million in cash and more than 21 million shares of the company he founded, now known as DigitalBridge. His son, Thomas Barrack III, ex-wife Rachelle Barrack and Jonathan Grunzweig, a DigitalBridge executive, all signed over their personal residences. His lawyers also promised to relinquish Barrack’s U.S. and Lebanese passports.

Barrack, 74, was not present during the hearing in downtown L.A., and his attorneys and relatives appeared remotely. Since his arrest Tuesday, he was held in the West Valley Detention Center in Rancho Cucamonga and was freed with a GPS monitoring bracelet.

After leaving jail, Barrack thanked the “fine men and women” of the various state and federal agencies involved in his incarceration.

“They have difficult jobs and carry them out with great professionalism,” Barrack said in a statement. “I also want to recognize the grace and humanity of the gentlemen with whom I have shared a community over these last three days. I am innocent and will prove that in court.”

During his four days at the 3,340-bed lockup, Barrack resigned from the boards of USC, First Republic Bank and DigitalBridge.

Earlier Friday, Barrack’s codefendant, Matthew Grimes, 27, was also ordered released in lieu of a $5-million bond that was secured by his parents, Brett and Marisa Grimes, a brother, as well as his parents’ Santa Barbara residence.

Both men were ordered to appear Monday for arraignment at a federal court in New York.

After Barrack’s arrest, prosecutors had sought to keep him in custody, arguing that he posed a flight risk given that he is “an extremely wealthy and powerful individual with substantial ties to Lebanon, the UAE and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.”

Authorities noted he had taken more than 75 international trips aboard his private jet over the last five years, including a trip to the Emirates as recently as March. Prosecutors also indicated Barrack had significant foreign assets — and extensive overseas ties — that would “allow him to live comfortably as a fugitive for many years to come.”

The fallout was swift after Donald Trump pardoned Robert Zangrillo, who had faced a criminal trial set for this year.

As part of the terms of his release, the magistrate prohibited Barrack from having contact with Emirati or Saudi Arabian officials; limited his travel to the parts of New York and California included in the federal court system’s southern and eastern districts of New York and the Central District of California; required him to travel only by car or commercial air carriers; and mandated that Barrack provide the government with itineraries well in advance of traveling between New York and California.

In the seven-count indictment, Barrack was accused of conducting a secretive, years-long effort to shape Trump’s foreign policy as a candidate and, later, president to the benefit of the Emirates.

The indictment said four Emirati officials “tasked” Barrack, Grimes and a third man, Rashid Al-Malik, with influencing public opinion through media appearances; molding the foreign policy positions of the Trump campaign and, later, the Trump administration; and developing “a back-channel line of communication” with the U.S. government that promoted Emirati interests.

Prosecutors allege Barrack directly lobbied the Trump administration to forgo a Camp David meeting between Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates during a multinational blockade of Qatar and arranged numerous contacts between Emirati officials and members of the Trump campaign and administration.

In a letter to the magistrate, prosecutors indicated Barrack’s work also benefited Saudi Arabia, although he was not charged with working on that nation’s behalf. Authorities did not allege Barrack was paid for his work, but according to published reports, a sovereign wealth fund of the Emirates did invest in the firm Barrack founded, Colony Capital.

Despite his relative youth, Grimes became a trusted intermediary between Barrack and Al-Malik and “repeatedly expressed his willingness to act at the direction of UAE officials,” according to the memo prosecutors sent to the magistrate.

Grimes worked for Barrack, became his close confidant and recently listed Barrack’s $15-million Aspen, Colo., home as his primary residence. As part of his work, Grimes joined the businessman on dozens of international trips, and prosecutors said he had “access to [Barrack’s] vast financial resources and private aircraft.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.