A rising actor, fake HBO deals and one of Hollywood’s most audacious Ponzi schemes

- Share via

The promise of easy money brought Jim Russell to a bar at the Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills.

Russell, a steel company executive from Las Vegas, had come to meet Zachary Horwitz, a low-level actor seeking investors for his film company.

Horwitz made it sound simple: He would use Russell’s money to buy the rights to cheap movies — “Slasher Party,” “Satanic Panic” and the like — and then resell them to HBO for distribution in Latin America. He’d pay Russell back in six months with a 15% profit.

Russell had already wired Horwitz more than half a million dollars after a friend vouched for the 30-year-old actor.

Now, Horwitz was offering a chance to invest much more.

At dinner that night in 2017, Russell was intrigued but nervous. What would happen if HBO declined to buy the rights to a film, he asked.

“HBO has never backed out,” Horwitz replied, according to Russell.

Over the next two years, Russell and his partners made $80 million in loans to the actor’s company. They thought they were financing scores of deals to buy and sell film rights.

In reality, they’d been lured into what federal investigators describe as one of the most audacious Ponzi schemes in Hollywood history.

Horwitz collected $690 million from investors for movie deals authorities say were fictitious. The HBO and Netflix contracts he used to convince Russell and others that his business was legitimate were forgeries, the government says.

For years, Horwitz kept the con going by using loans from one group of investors to repay what he’d borrowed from another, according to a federal criminal complaint. The investors are now trying to recover $235 million that he never repaid.

The alleged scam opened a money spigot that enabled the actor to live like a studio boss in a lavish Westside home with a screening room, prosecutors say. Horwitz traveled by private jet.

His April 6 arrest on a fraud charge followed a century-old Hollywood tradition of accused swindlers running get-rich-quick schemes that exploit investors’ attraction to the glamour of a movie business they know little about.

Actor Zach Avery forged Netflix and HBO emails in sweeping fraud, the FBI says.

Hundreds of emails, text messages and other documents filed in court in Los Angeles and Chicago reveal the vast scale of Horwitz’s operation and show how it ultimately spun out of control. Lawyers for Horwitz, 34, did not respond to requests for comment.

His alleged victims include three of his close friends from college, who roped in parents, grandparents, siblings, in-laws and others, some of whom lost their retirement savings, said Brian Michael, the friends’ attorney.

“It’s been financially catastrophic and emotionally devastating,” he said.

The financial collapse came just as Horwitz’s acting career — under the screen name Zach Avery — was taking off. He starred last year in “Last Moment of Clarity” with Brian Cox, who plays the patriarch Logan Roy on the HBO series “Succession.” He also has a leading role in the upcoming thriller “Gateway,” a feature film with Olivia Munn and Bruce Dern.

Two filmmakers said producers sometimes “attached” Horwitz to a cast regardless of talent.

In a scene from “Trespassers,” a 2018 horror film shot in Malibu, Horwitz writhes on the deck of a swimming pool with a thick dagger plunged into his belly. The director, Orson Oblowitz, was unimpressed by his acting, but he also said he wondered whether the actor’s arrest might bestow “a new cult status” on the movie.

“It’s mind-blowing,” he said. “This dude does not strike me as a criminal mastermind. I am amazed.”

An inattentive SEC was key to the success of Madoff’s fraud. Its exposure put pressure on the agency to tighten enforcement — until Trump came along.

::

Horwitz was a psychology major and football jock at Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind., when he befriended fellow undergraduates Jacob Wunderlin, Joseph deAlteris and Matthew Schweinzger. Horwitz stayed close with them after graduating in 2009, attending each of their weddings.

Wunderlin and DeAlteris got finance jobs at J.P. Morgan and settled in Chicago. Schweinzger went to work for Morgan Stanley in New York.

Horwitz also moved to Chicago, where he launched FÜL, a short-lived “fast casual restaurant with a healthy twist,” as he put it.

But Horwitz, who had grown up in Tampa, Fla., and Fort Wayne, Ind., aspired to be a film actor. After two years in Chicago, he and his girlfriend, Mallory Hagedorn, drove to Los Angeles with their Rottweiler, Lucy, for a fresh start.

This dude does not strike me as a criminal mastermind. I am amazed.

— ‘Trespassers’ director Orson Oblowitz

“Feet on the dashboard, cruising with my best friend to a new place to call home,” Hagedorn tweeted on the way to California in January 2012.

They found an apartment in the city’s Miracle Mile neighborhood. Hagedorn enrolled in cosmetology school and became a hair stylist at a West Hollywood salon.

Horwitz hired an acting coach and went on the audition circuit. He had trouble winning parts but made friends with two brothers who helped him break into show business: producer Julio Hallivis and his brother Diego, a director.

With Julio Hallivis, Horwitz co-founded 1inMM Productions, short for One in a Million. It would finance low-budget horror and science fiction films with increasingly prominent roles for “Zach Avery.” Diego Hallivis directed some of them.

In 2013, the company announced a partnership with Miami producer Gustavo Montaudon to distribute films in Latin America. Montaudon was a seasoned player in the field — a former 20th Century Fox vice president who had overseen licensing of the studio’s TV shows in the region.

As Horwitz began soliciting investors, he told them Montaudon and Julio Hallivis were key players in the deals that are now alleged to be fake, according to court papers filed by the government. He called them “principals” in 1inMM Capital, his new film rights company.

Montaudon was responsible for “deal relations” with HBO, Netflix and Sony, Horwitz claimed in a report to investors. He identified Hallivis as chief of the company’s Latin America distribution arm, in charge of content acquisition and relations with foreign sales agents.

Both Montaudon and Hallivis denied participating in the alleged Ponzi scheme.

Montaudon, in a quick phone interview that he cut short, called Horwitz “just a guy I met a long time ago.” “I don’t have a relationship with him,” he said. “I don’t know what he was doing. I have no idea.”

Hallivis’ attorney, Marshall A. Camp, said in an email that the producer was “shocked by the allegations against Zach Horwitz and did not have any role in the criminal scheme alleged.”

The FBI complaint charging Horwitz with wire fraud accused no one else of wrongdoing.

The first college friend Horwitz approached for money was Wunderlin, who — with a partner — lent $37,000 to 1inMM Capital in 2014. Horwitz personally guaranteed the loan and repaid it with interest on time.

Wunderlin and his wife flew to Los Angeles a few months later for the wedding of Horwitz and Hagedorn at the Four Seasons.

Over the next six months, Wunderlin, DeAlteris and Schweinzger got family, friends and associates to join them in lending $1 million more to 1inMM Capital to buy rights to seven movies supposedly licensed to HBO and Sony. Those loans were also promptly repaid, Wunderlin said.

To keep the money flowing, Horwitz talked up his connections. He told his friends that he’d worked for the Seattle venture capital firm Maveron and had financial backing from its co-founders Dan Levitan and Howard Schultz, the former Starbucks chief executive, according to Wunderlin. He claimed Levitan and Schultz had opened doors for him at Netflix, HBO and Sony.

Levitan denied Horwitz worked for Maveron.

“I’ve never met him,” Levitan told The Times. “I’ve never introduced him to anybody.” Schultz could not be reached.

Emboldened by Horwitz’s repayments, the Chicago group formed a company to invest in more movie deals. For five years, the group’s network of “downstream investors” kept growing beyond the original trio, their family and friends. By the end, the Chicago group would put up $490 million in loans.

The deals came with extensive documentation that made them look real.

In one case, the Chicago group lent $1.4 million for Horwitz to buy the rights to an Italian film, “Lucia’s Grace,” and resell them to Netflix for distribution in Chile, Argentina, Brazil and a few dozen other countries. Horwitz promised to repay them $2 million a year later.

Horwitz sent his three friends a 20-page “license agreement” purportedly signed by a Netflix executive to authenticate the deal — a counterfeit, according to prosecutors. How Horwitz obtained model Netflix contracts to copy — with requirements as specific as the minimum screen resolution — is unclear.

Horwitz was sending similar documents to Russell and the others in the Las Vegas group. To them, the Chicago investors’ booming business with Horwitz looked like a threat in the weeks after they met him at the Four Seasons.

Romik Yeghnazary, a Las Vegas home loan officer, told Russell, his friend and tennis partner, that they were competing with people in Chicago for scarce and lucrative film loans.

Yeghnazary — from the start more eager than Russell to lend Horwitz money — said he was trying to “swat those guys away and to get us first right of refusal on all deals that come in.”

In emails full of typos in 2017, Yeghnazary urged his partners to finance deals for four more films — among them a slasher-in-the-woods flick called “Ruin Me.”

“This is the goose that lays the golden egg guys, lets just hope they keep coming month after month,” Yeghnazary wrote, suggesting they “ride this baby out as long as we can.” He brushed off Russell’s annoyance at Horwitz for refusing to let them see his business records.

“If anything not sending us financials proves to me even more that they are not desperate, they don’t need our money,” Yeghnazary wrote.

“It is absolutely ridiculous that he does not want to share his financials as we are currently lending 5mil,” Russell replied. “This is a very common practice to ensure the company is making money, has sales, and has the ability to pay. Sorry, I am not risking millions based upon someone’s word, who I don’t know.”

The next day, Yeghnazary tried to calm his partner. He sent Russell a corporate registration he’d found for 1inMM Capital on the internet.

“Keep in mind please that our HBO contracts we are getting show that they will always have enough money for us, since HBO is sending them the minimum guarantee funds,” he told Russell. “Also keep in mind I verifies those contracts diresctlu with HBO.”

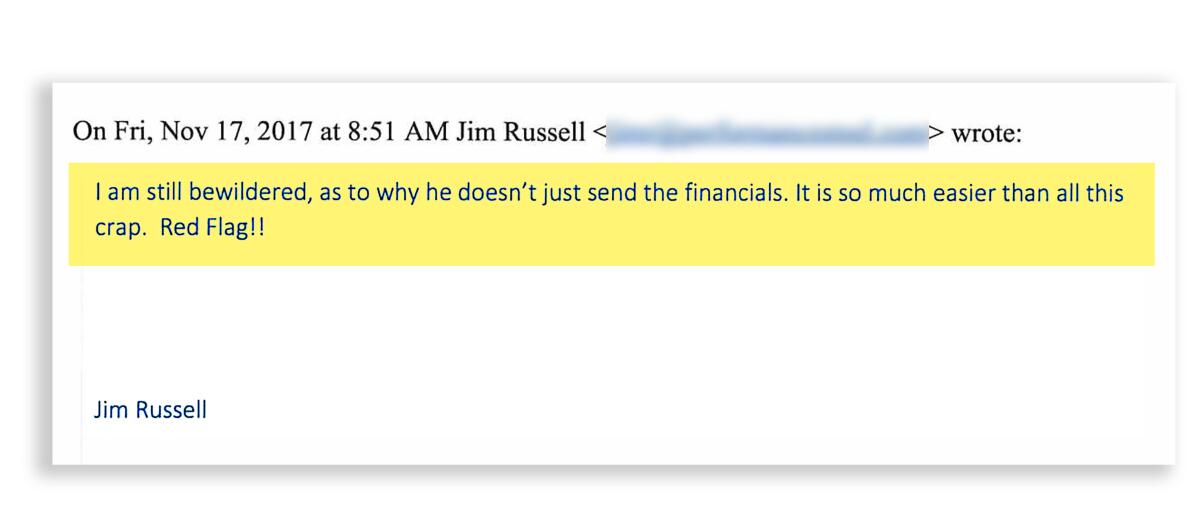

“I am still bewildered, as to why he doesn’t just send the financials,” Russell wrote back. “It is so much easier than all this crap. Red Flag!!”

The Las Vegas group nonetheless kept wiring money to Horwitz.

::

Horwitz abruptly stopped paying back his investors in late 2019; the reason is not yet clear. By then, Horwitz and his wife were well settled with a toddler son in their six-bedroom Beverlywood house with a pool, gym and 1,000-bottle wine cellar. Horwitz liked to play the grand piano.

Their lifestyle had improved dramatically. Horwitz spent $5.7 million on the house, $165,000 on high-end cars, $137,000 on private-jet trips, $125,000 on jaunts to Las Vegas and $55,000 on a luxury watch subscription, the government says. In 2018, his American Express charges hit $1.8 million.

As payment demands and lawsuit threats piled up, Horwitz tried to keep investors at bay by insisting Netflix and HBO were late in paying what they owed. The back-and-forth was detailed in federal court filings by the government.

“Zach, please give us an update,” Russell texted him in March 2020.

He wanted to know whether HBO had set any dates for payment.

“Don’t have any exact info on dates,” Horwitz told him.

Money from HBO was mired in “multiple layers of red tape” due to a corporate merger, Horwitz claimed, but “Gustavo” had been “a huge help.”

“Don’t you think it’s strange that no one’s paying you?” Russell asked.

Horwitz said many HBO vendors, not just 1inMM Capital, were having trouble getting paid. The next day, he refused Russell’s request for a copy of a purported email from HBO. He urged Russell not to contact HBO.

“Not trying to cause any more headaches — just need to be smart about where we are in the process and cannot jeopardize everyone’s deal if HBO decides there has been a confidentiality breach,” Horwitz texted.

Russell told him that “this new hide-the-ball position that you have taken raises a lot of suspicion.”

“There should be absolutely no suspicion,” Horwitz replied, “as I clearly am working diligently to resolve the issue every single day.”

For the rest of 2020, Russell dogged him for payment of $22 million in overdue loans — to no avail.

For the group in Chicago, the stakes were even higher. Not only did they have a bigger portfolio of delinquent loans, but they were also facing payment demands from their “downstream investors.”

Among them was Marty Kaplan, a Chicago finance executive whose family, with partners, stood to lose $10 million.

Kaplan had recently met with DeAlteris — one of Horwitz’s college friends — and discussed the investment risks. DeAlteris told him that “99% of his and his family’s money” was invested in Horwitz’s deals with HBO and Netflix, according to court papers filed by a Kaplan attorney.

“I wouldn’t be able to pay rent if something went wrong,” DeAlteris told Kaplan, according to the attorney.

Once everything started going wrong, the Kaplans were the first investors to sue.

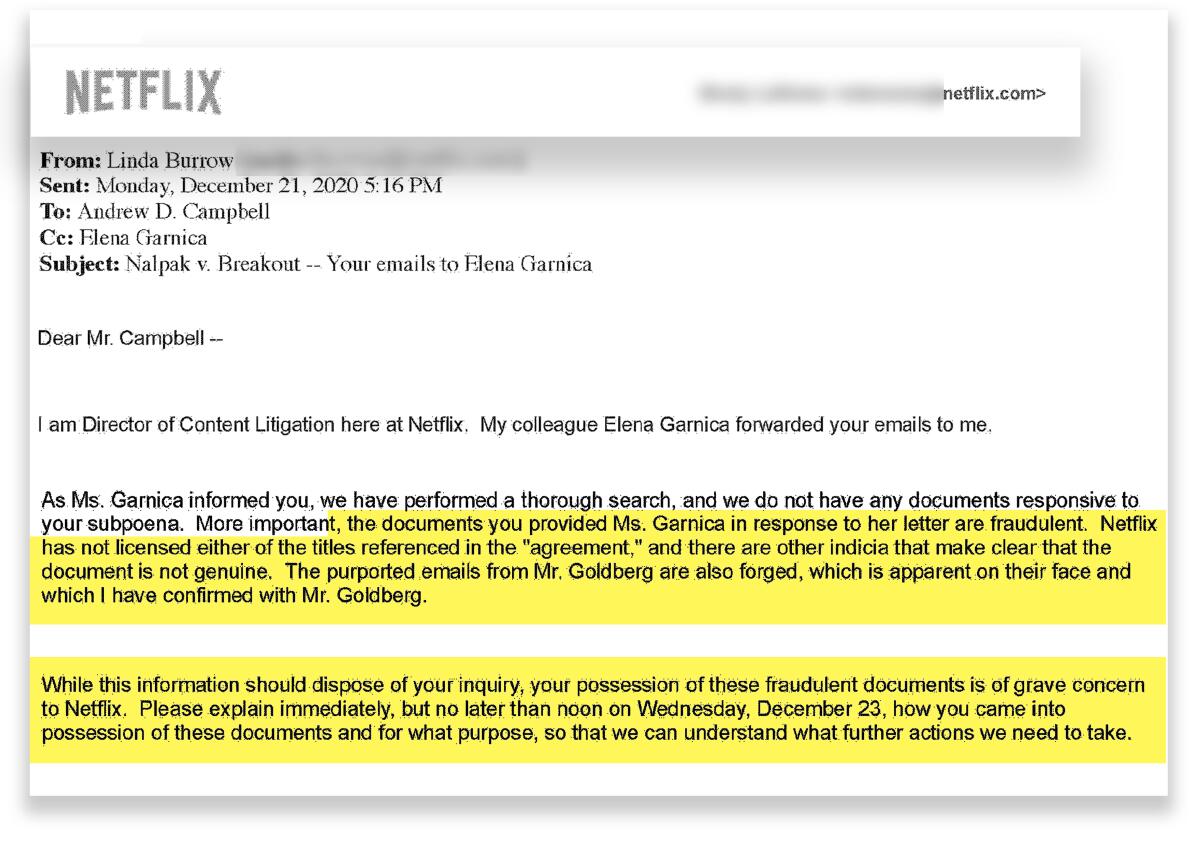

The family’s attorney subpoenaed Netflix in December 2020 for records on its payments to 1inMM Capital for distribution rights on “Tulip Fever” and 18 other movies.

The response was puzzling: Netflix claimed to have no record of doing business with Horwitz’s company, federal court records show.

“While we appreciate your response,” the Kaplans’ lawyer wrote back, “we do not believe that Netflix has performed a reasonably diligent search of its files.”

To prove his point, the lawyer attached a license agreement between Netflix and 1inMM Capital for the documentaries “Active Measures” and “Divide and Conquer: The Story of Roger Ailes.” The next day, he forwarded an email exchange between Horwitz and a Netflix lawyer.

The documents tripped a cascade of alarms. Once the Netflix legal team understood what Horwitz was up to, it was only a matter of time before investors and federal investigators would find out too.

The contract was “fraudulent,” a Netflix attorney told the Kaplans’ lawyer. The email was “forged.”

“While this information should dispose of your inquiry, your possession of these fraudulent documents is of grave concern to Netflix,” she wrote. “Please explain immediately … how you came into possession of these documents and for what purpose, so that we can understand what further actions we need to take.”

With his financial standing deteriorating, Horwitz and his wife put their house on the market in January. The asking price was $6.5 million.

A few weeks later, Netflix sent a cease-and-desist letter to a lawyer for 1inMM Capital, Luke Steinberger of K&L Gates. It demanded that Horwitz stop circulating fabricated Netflix emails and contracts as if they were authentic.

The response was terse. “This is to inform you that K&L Gates is no longer representing 1inMM,” Steinberger wrote.

Horwitz followed up with his own email to Netflix on Feb. 23.

“First and foremost, apologize for any delay in response and the fact that these unfortunate allegations are being discussed at all,” he told the company’s content litigation director. “I am looking into the matter and have informed any/all parties that may have been involved of the situation. Thank you.”

The next day, Irvine businessman Scott Cohen emailed the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission about a feared $15-million loss in “what appears to be a Ponzi scheme” run by Horwitz.

“I have a group of investors that includes around 35 people that have been waiting for nearly 13 months for payment,” Cohen told SEC lawyer Lance Jasper. “People are beyond the point of me managing them and they are really in need of answers.”

The SEC subpoenaed Horwitz that day for his personal financial records and those of 1inMM Capital.

The SEC had been combing through Horwitz’s bank records for weeks. His former Chicago friends had reported him to the FBI and were cooperating in the criminal investigation. They were also threatening to sue Horwitz over $165 million in overdue loans.

Undeterred, Horwitz kept telling them he was working on securing payments from Netflix and HBO. In a March 12 email to Wunderlin, DeAlteris and Schweinzger, he said investors’ accusations of wrongdoing were causing “massive issues for 1inMM and myself personally.”

“I am complying with every single thing that is being asked of me and doing absolutely everything I can to assist, facilitate and explain whatever is needed but right now — it is a problem,” he wrote.

Horwitz’s film company soon lost another marquee law firm. A spokesman for Kendall Brill & Kelly said it severed ties with 1inMM Capital in March, “when we were unable to verify information about several of its purported transactions.”

On April 1, the FBI secured a warrant to track Horwitz’s whereabouts with location data from his mobile phone. Four days later, the FBI got another warrant to search his house for evidence of suspected securities, mail and wire fraud; aggravated identity theft; and money laundering.

FBI agents raided the house, by then in escrow, and arrested Horwitz at dawn the next day.

The SEC got a court order to seize his assets. Its initial look at his bank balances showed his personal account had dwindled to $3,297.

An SEC fraud examiner reported finding four “1inMM” accounts. There was $3,224 in one of them, $306 in another. The third was down to $5. The fourth was empty.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.