Why is L.A. obsessed with fireworks? (The answer involves a 1980s sex scandal)

- Share via

The Fourth of July is more than three months away, but why not start freaking out about fireworks now, and beat the rush?

The deadly fireworks explosions in Ontario last week — at least two humongous ones amid an hours’-long spectacle of pyrotechnics going off — has shoved the topic higher up the calendar. Bomb experts found at least 60 boxes’ worth of fireworks that hadn’t blown up, so imagine how much stuff was originally jammed into that nice house in that nice quiet city. None of it was legal; the city makes it clear online: “You may not sell, buy, transport, store, or use fireworks in the City of Ontario.”

And yet there they were.

And there they are, all over California. In certain cities and counties, you can buy and sell and set them off legally, but only the state fire marshal-approved “safe and sane” devices, the ones that don’t go boom, or go up in the air, or swerve around on the ground.

In California, since 1973, only “safe and sane” fireworks can be sold at all to ordinary folks. Explosives like M-80s, and the legendary cherry bombs that high school pranksters deployed to shatter boys’ room toilets? Illegal nationwide since 1966. In my little Midwestern hometown, the local law, Sheriff Cecil, would come around early every July and gather us kids and flip up his eyepatch and point to the scar and say, “See that? Fireworks done that.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

In hundreds of places — like the city of L.A. and L.A. County’s unincorporated areas — you and I cannot buy or sell or set off “safe and sane” gizmos at all.

This weird patchwork legal geography is the way it is all across California.

If, for example, you live in Los Angeles city’s Harbor Gateway strip connecting the bulk of L.A. to San Pedro, you can cross the city limits into Carson and buy fireworks legally there. You can do the same if you live in the Valley near the incorporated city of San Fernando, where fireworks can be sold.

But if you bring them back to your house in L.A., you’re breaking the law.

And who knows how many tons of pyrotechnics that are completely illegal in California — the unsafe and insane whiz-bangs, the bottle rockets, Roman candles and aerial spinners — get bought legally in Nevada and just driven back here, illegally, from vacay.

How do you enforce these laws? Who remembers reading about the last time anyone got busted for even “safe and sane” fireworks in L.A., let alone those lawless widow-maker explosives? Yet in almost every L.A. neighborhood, the Fourth of July stuns the ears like the Battle of the Somme, and palm trees leap into flames like a scene from “Apocalypse Now.”

Apart from speeding, and noxious gasoline leaf-blowers, fireworks bans are probably the most ignored laws in California. On a website where L.A. County supervisor Kathryn Barger reminded residents of the ban, a fireworks-defier named John dared the law, “Try to get me, -------------!”

But we’re stuck with this haphazard quilt. I’ve been reading decades of Times’ stories of rattling debates over banning and unbanning fireworks sales in small L.A. County cities like San Fernando or El Monte. Almost half of the county’s 88 incorporated cities let you buy them, usually during the June 28 to July 6 holiday span.

Why is it like this? In a state where brush fires and air pollution are powerful arguments, why not an outright ban on consumer fireworks, like in Massachusetts, the one state that does?

Let me direct you to a quartet of reasons:

One, John Adams, a founding father with a temperament almost as explosive as a firecracker. In July 1776 he wrote with gusto to his wife, Abigail, that the nation’s new independence would be marked “with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations [fireworks] from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” Civic bodies ever since have had to pass fireworks bans over the ghostly wishes of our second president.

Two, until bans of decades past, “backyard” fireworks were sometimes powerful festive munitions that went by names like “devil on a walk” and “automatic torpedo.” They burst forth with cyanide and phosphorus and arsenic.

And Fourth of July carnage was as routine as New Year’s Eve drunken driving smash-ups. The Times in 1900 laconically noted under the headlines “Usual Fourth of July Casualties … Cheerful Idiots in Evidence” a man who tried to light a “dud” firecracker with a searing-hot piece of metal and lost a forearm and an eye. Seven people standing too close to exploding mortars at a Columbus Day fireworks fest here in 1892 were killed; nine months later, the man who had run that show lost his left forearm when his fireworks shop on the edge of downtown L.A. blew up around him. A city ban on fireworks of any kind was passed during World War II and has stayed on the books.

Three, small towns’ service clubs like the Rotary or Lions sometimes make a huge part of their annual nut by selling fireworks, and they carry a lot of sway with their cities’ councils.

Angelenos can be spotted a mile away in other locales, waiting for the walk sign while locals jaywalk with abandon. What’s that about? And what happens when people do jaywalk here?

And four, an astoundingly bold Sacramento fireworks lobbyist in the 1980s generated a flesh-and-the-Red-Devils, hookers-and-cash political scandal that today we might call … what, Boomgate?

W. Patrick Moriarty got into the fireworks biz as a kid in Tacoma, Wash. As he once told the San Bernardino Sun, at a World War II auction of goods taken from interned Japanese Americans, he bid $15 for what he thought was an armload of fireworks. It turned out to be a truckload. He couldn’t set them off because of wartime rules, so he locked them away in the garage and as the country celebrated V-E Day, in April 1945, Moriarty opened a fireworks stand the way other kids open lemonade stands. He cleared nearly $1,800.

Fireworks would thereafter be his big business. In Sacramento, as a fireworks magnate, he was a big noise — and he made one. He schmoozed and dropped big, sometimes covert, campaign donations. He pressed the flesh — and provided it, with prostitutes at fancy shindigs.

In 1981, he was the motive force that got the whole legislature — Democrats and Republicans, Assembly and Senate — to pass a bill that would have meant that no California city or county could ban his “safe and sane” fireworks. It would have doubled his multimillion-dollar income.

One state senator told The Times that the lobbying for the bill by fellow senators, beneficiaries of Moriarty largesse, was intense. “They came on the floor and stood around me in an intimidating fashion. I said, ‘No way.’” Only Gov. Jerry Brown’s veto stopped it.

Starting in 1983, scrutiny by The Times and law enforcement began shaking loose the details of Moriarty’s dealings. A half-million dollars had sweetened and swayed three years of the people’s business in Sacramento. At least 17 public officials were soiled by this scandal. The entire Legislature was walking on eggshells. Two sentences into any conversation and the name “Moriarty” likely popped up. A Democrat butting heads with a Republican over this said it was a good thing dueling was outlawed, but how about a boxing match, three rounds, to benefit charity?

I mean, this was juicy.

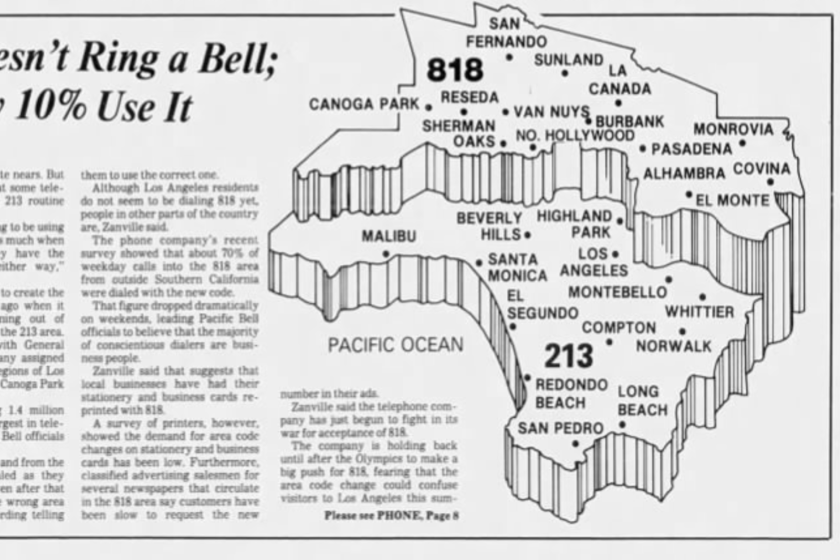

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

It even turned out that L.A.’s then-fire chief had secret ties to Moriarty over bank loans and real estate. As fire chief, he had twice urged the city to legalize “safe and sane” fireworks of the kind Moriarty sold. The City Council said “no” both times.

As investigators closed in, Moriarty supposedly pressed a Glendora Republican state senator, H.L. Richardson, to block the inquiry — especially the stuff about hookers, so embarrassing. But Richardson hurried right off to prosecutors, and told The Times that Moriarty had said to him: “‘Well, we had some parties and you know how some of those whores and prostitutes show up.’ … He made it sound like they just stumbled by.”

Moriarty had also opened up a second front. He sued San Jose over its fireworks ban, and the state courts sided with Moriarty: Cities and counties, even in fire-danger zones, couldn’t prohibit fireworks sales. An urgent bill zipped through the Legislature with “some help from the outside,” said its sponsor — meaning the criminal investigations that no legislator wanted to tangle with.

So two weeks before the Fourth of July in 1984, Gov. George Deukmejian — himself an unwitting beneficiary of laundered Moriarty money — signed the law restoring to cities and counties the power to ban “safe and sane” fireworks.

Two years later, Moriarty was sentenced to seven years in prison. His misdeeds took down one of his own associates, a bank official, three council members in the city of Commerce, where Moriarty ran his business, and Assemblyman Bruce Young, a Moriarty protégé and lieutenant of Assembly speaker Willie Brown. Young’s mail fraud convictions were thrown out on appeal.

So when the headlines called this scandal “explosive,” they were right. Fireworks bills still show up in the Legislature, mostly about making it harder to get them and the penalties stricter. Sen. Mark Leno, a San Francisco Democrat, sees how the argument lines up: “The supporters of the industry would frame it in terms of liberty and freedom, and it’s all wrapped up in the Fourth of July. One side of the debate is: This is our heritage, ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ the rockets’ red glare. And all that gets mixed up with what is in my perspective a public safety and public health issue. The debate keeps coming back very much to climate change and our ever-growing fire season.”

And lastly, because even a flash-bang fireworks and politics scandal can’t hold a candle to celeb culture, I’m throwing in the Kardashians, who, in 2015, at midnight on Aug. 26, pulled this stunt: Eight obnoxious minutes of thunderous professional fireworks exploded above their party yacht offshore from Marina del Rey. It turns out it had the approval of the county Fire Department, but not of the thousands of humans and dogs awakened and alarmed from Santa Monica to Redondo Beach.

Even Moriarty might not have had the chutzpah to pull that off.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.