San Pedro, Los Feliz, even Los Angeles: Why do we pronounce our place names this way?

- Share via

You say “San Pay-dro,” I say “San Pee-dro” — let’s call the whole thing L.A.

It’s supposed to be a “tell” — that in Los Angeles, you can sort the locals from the pretenders and parachutists by how they pronounce certain place names, chiefly: Los Feliz, San Pedro, Sepulveda, and even the double-barreled name of our beloved burg, Los Angeles. The “tell” being that “real” Angelenos don’t pronounce these Spanish names the way that speakers of Spanish would.

For the record:

12:29 p.m. Feb. 23, 2021A previous explanation of the pronunciation of the Spanish name “Sepulveda” emphasized the penultimate E sound. The correct pronunciation is “seh-POOL-vay-dah.”

The fact that this is still a point of friction 240 years after L.A. was founded is like the mashup saga of the city itself: an outpost of Spain, taken over by Mexico, on-rushed by Yankee immigrants who went from guests to conquerors, and now the mirror-gazing scrutiny of a world-city of immigrants asking itself again and again, who are we, really?

First, San Pedro: By turns a Tongva boatmen’s settlement, the Rancho San Pedro — mini-kingdom of an ordinary soldier — a fishermen’s town, a port and a fort, and the Everyman neighborhood tethered to the big-bellied city by gerrymandering and commerce. It pronounces it the way it damn well wants, and in the main, it wants “San Pee-dro.” Someone who suggested on a long-ago discussion board that this is because “everyone there [is] just a moron” got properly pummeled.

Los Feliz: Another Tongva property given away as a rancho kingdom, granted to the Feliz (say “Fay-LEASE”) family. In English-speaking mouths it became “Loce FEE-lus.” Half of it is Griffith Park, a Welsh name which practically nobody pronounces as anything but “Griffith.”

Sepulveda: Yet another baronial rancho. The “seh-POOL-vay-dah” family was one of the Californios’ most substantial, and now it has L.A. County’s longest street, Anglicized as “seh-PULL-vuh-duh” Boulevard, keeping the family name green if not precise.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

And the grandmama of them all, Los Angeles, a town almost a quarter-millennium old and still we wonder: Do we say the Spanish name Spanish-fashion, or give it up to the reinvented city’s “manglo” (mangled + Anglo) pronunciation?

I see this as a break-point of ages and stages: The Spanish-speaking domain of Spain and then Mexico; the dawn of Yankee California and statehood, when the new constitution required public proceedings in both Spanish and English; the human tides from the Midwest and East Coast that elbowed aside the Latino population as an active political and living-language presence, and replaced it with sentimentalized caricatures of missions and senoritas and Spanish names in Iowa accents. And threading through it like a low-grade fever, effacing and degrading Spanish and Spanish speakers as lowbrow, and mispronouncing words and names to demonstrate it’s not a lingo worth bothering about.

Happy to say that Reynaldo F. Macias pretty much agrees with me about that arc. He’s a professor of Chicano/Chicana studies, education and socio-linguistics at UCLA. Don’t forget, he reminds me, that Spanish, not English, was the first non-indigenous language in North America. Yet in studies of a few decades ago, “you had a hierarchy of how accents were viewed and valued. French was up there, German was somewhat up there, but Spanish was way down there.”

Sometimes the mispronunciation is driven by hostility; sometimes it’s familiarity and habit. When Macias was in college, a group of friends and dormmates drove up to the Stanford-UCLA game and the driver “wanted to stop off at his parents’ home in ‘Las Gattas.’”

“We went up almost 500 miles and then I see the sign that we’re entering the city, and it’s ‘Los Gatos.’ A lot of this is what you hear and when you hear it.”

We want to hear from you

Today’s column was inspired by a question from a reader. What do you want to know about life in and around L.A.?

“Mock Spanish,” as Mariška Bolyanatz Brown tells me, is Spanish-with-malice, a racist word-theatre in anti-immigrant politics, or the clumsy jokes of people who say they mean no offense but give it anyway. She is an assistant professor of Spanish and linguistics at Occidental College, and she overhears this a lot: “People see it as so minor: ‘How can people think I’m a racist if I say ‘el cheapo’?

“You’re connoting that Spanish is less important or complex; you don’t speak Spanish but you can speak Spanish — just add an O to everything.”

Ha ha. Not.

I find myself among Angelenos who speak passable Spanish, but I feel self-conscious and even a little affected when I use a Spanish name with Spanish pronunciation in the middle of an English conversation. That’s fine, she reassured me. She’s a fluent but not native speaker, and when she’s in an English conversation with someone who says “El Sah-GUN-do,” instead of “El Seh-GOON-doe,” and the goal is just to be understood, and it’s innocent and not malicious, she’ll let it go.

As The Times noted in 2013, more newcomers and young Angelenos are trying to honor the language and the culture by pronouncing its proper names correctly. In time, the balance may tip back to 150 years ago.

My cherished nugget of L.A. Spanish “oops” is from about 40 years ago, when the L.A.-born monarchs of mini-malls named their company La Mancha Development, and made its logo a stylized silhouette of Don Quixote. As one of the company founders said years later, “We thought la mancha was Spanish for ‘impossible dream.’ Later, we found it’s Spanish for ‘the spot.’”

As in “stain.”

In all of our L.A. decades, the most quarrelsome pronunciation of all is the name of the city where we live.

Persistently and insistently, The Times’ masthead for a long time tried to dictate the pronunciation as “Loce Ahng-hayl-ais.” The paper’s first city editor, Charles Lummis — self-taught ethnologist, founder of the Southwest Museum, a man who swaggered across the pinstriped landscape in his own “native” costume of sombrero and green corduroy suit — thundered his rendering of the city name: “The ‘g’ shall not be jellified!” It should be a hard G, as in, well, “Anglo.”

But the hard-G came out with a nasal twang as flat as the Midwest where so many new Angelenos hailed from. With my own ears, I heard the Nebraska-born mayor Sam Yorty pronounce it this way, and I heard it, too, from the third publisher of this newspaper, Otis Chandler.

In 1952, then Mayor Fletcher Bowron became exasperated with being asked on his travels how to pronounce his city’s name. So he punted it to a jury of 20 experts — a hung jury, as it turned out, split between “Loss An-jell-ess” and “Loss An-guh-less.” The jury ruled out a version slightly closer to Spanish, “Lose-Ong-ha-less,” as “too unusual.”

The mayor — a “hard-G” man — consoled himself that “civic pride” would keep the good people of Los Whatchamacallit from “ever, ever referring to it as ‘L.A.’“ Tell it to Randy Newman.

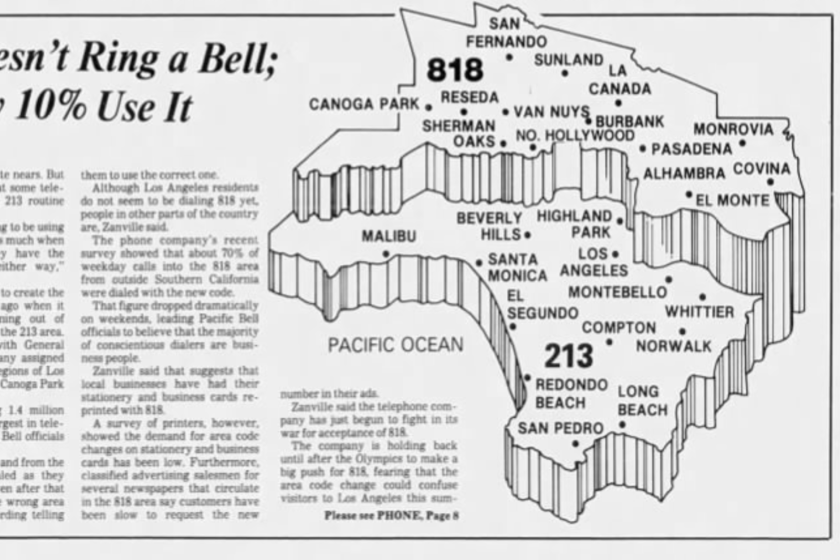

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.