Storm next week expected to bring ‘significant rain and mountain snow’ to Southland, forecasters say

- Share via

A storm system arriving during the second half of next week has the potential to bring widespread moderate to heavy rain to Southern California, the National Weather Service says.

Rainfall rates could be high at times, raising the possibility of debris flows in the recent burn areas, as well as mud and rock slides on mountain roads. Significant snow accumulations are possible with the storm, mainly above 5,000 feet.

The biggest storm, the third in a series, is predicted to incorporate an atmospheric river. Atmospheric rivers are concentrated streams of water vapor in the middle and lower levels of the atmosphere. Because they’re lower in the atmosphere, they tend to be warmer, even when they aren’t a pipeline directly to the tropics.

This atmospheric river will come more from the west, said Eric Boldt, a warning coordination meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard. “It’s not a direct tropical connection, but [has] above-normal water content that can bring steady moderate rain for many hours.”

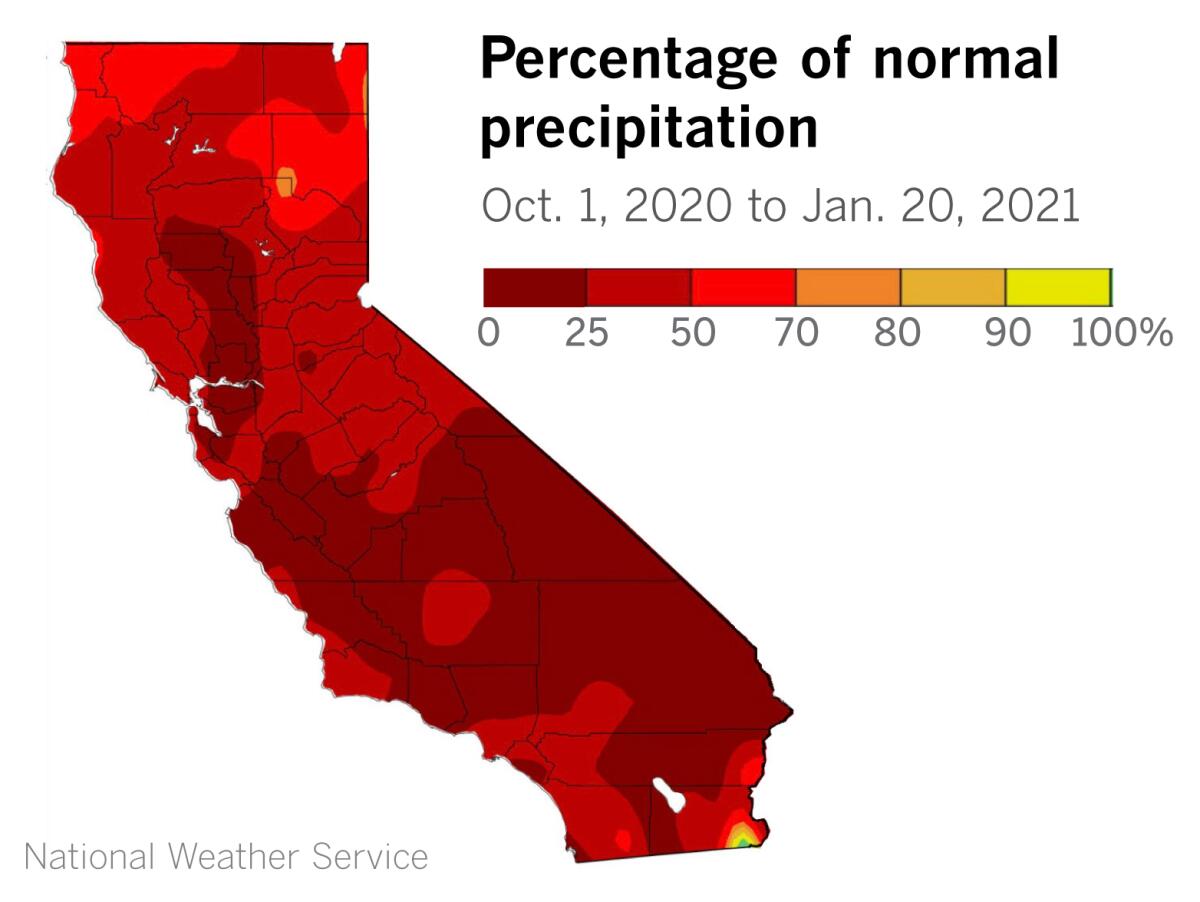

The pattern change comes after a summer that featured record heat, the worst fire season in California history and a dry fall and early winter raked by Santa Ana winds.

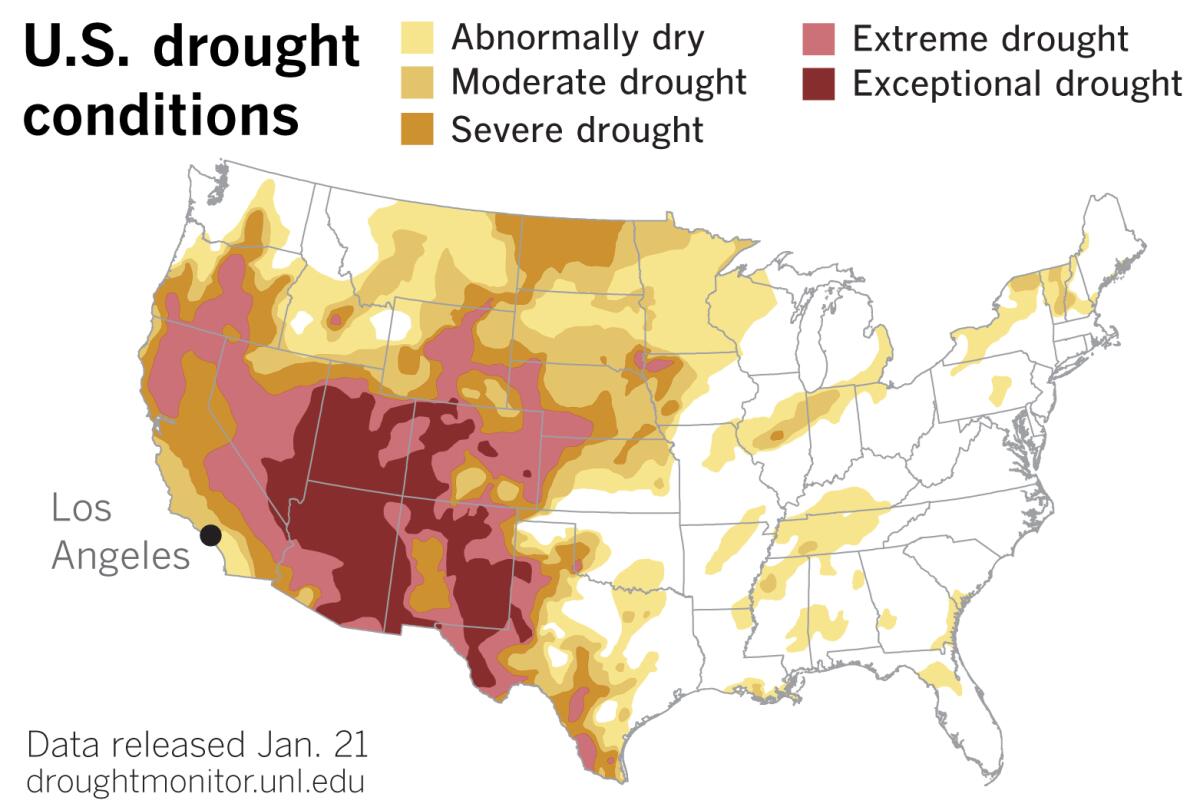

Though the Pacific Northwest and northern Intermountain West have enjoyed heavy precipitation from a series of North Pacific storms, the central and southern parts of the West are in drought that’s about as bad as it can get. With areas already classified as being in extreme and exceptional drought, “not much deterioration can be introduced,” the U.S. Drought Monitor reported on Thursday.

About the only way such a parched, scorched landscape could get worse would be to unleash heavy rain from an atmospheric river— rain that’s like a fire hose — washing mud and debris down rugged slopes. Rain is needed, but not all at once. If heavy rain rates occur, there is a risk of debris flows in recent burn scars such as those left by the Lake, Bobcat and Ranch2 fires, and other fires in Orange County and the Inland Empire.

Forecasters don’t expect an epic rain scenario, but warn that the public should pay attention to updates and follow the directions of authorities if they are told to evacuate.

Massive amounts of rain aren’t needed to create a dangerous situation. For example, the Montecito mudslide in Santa Barbara County on Jan. 9, 2018, following the Thomas fire, occurred after only about a half-inch of rain. But that rain fell in about 5 minutes, and produced debris flows 15 feet high.

How did we get to this point?

A La Niña is in place in the equatorial Pacific, and is expected to persist through the rest of the winter. La Niña typically results in a dry winter in Southern California and the Southwest, although that’s not always the case. El Niño, La Niña’s wetter cousin, usually means a wet winter in Southern California, based on history, but, again, there are no guarantees.

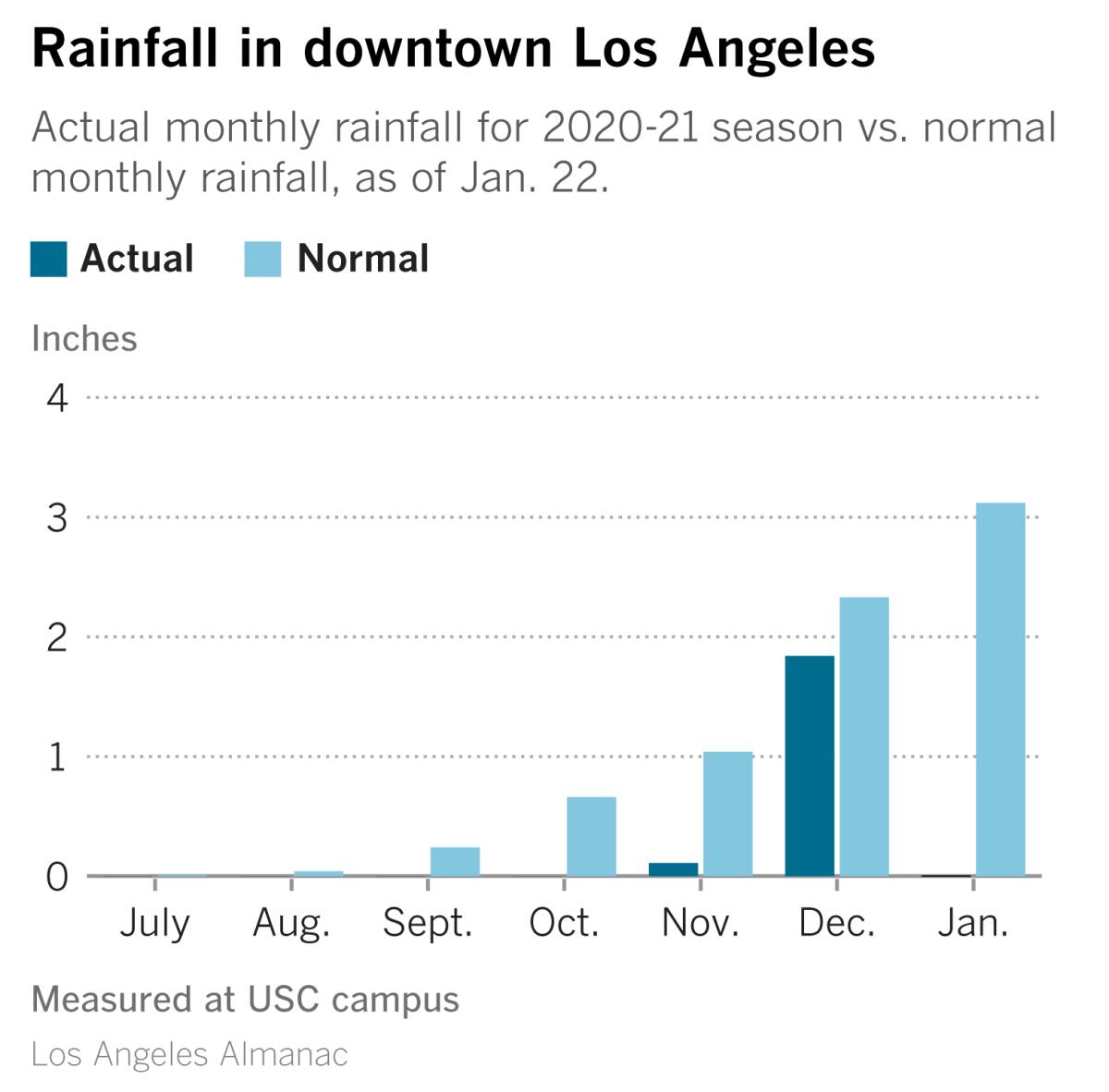

The Southland has seen one storm in the last nine months, and the dry pattern up to now has been consistent with a typical La Niña winter — which usually also features wetter-than-normal weather in the Pacific Northwest and across the Northern Tier of the United States.

Even though the Los Angeles region had nearly normal rainfall last winter, the excessive summer heat and dry Santa Ana winds in the fall and early winter have left fuels tinder dry. Numerous large fires burned more than 4 million acres in California in 2020, sometimes shrouding almost the entire state in smoke.

In a Mediterranean climate like California’s, rain falls mostly during the winter. Even without the influence of El Niño and La Niña, Southern California depends on five to seven significant storms for its rainfall each year.

“In L.A. it doesn’t rain or drizzle every day during the winter like it does in Seattle,” said climatologist Bill Patzert. “Rain comes in five, six or seven events. There are usually less than 20 days of rain, and less than 10 days of significant rain all season.”

The Los Angeles Basin is a flood plain. After a season that started out dry in 1937-38, two storms in late February and early March 1938 abruptly dropped as much rain on the region in five days as usually falls in an entire season. Catastrophic flooding from the foothills to Long Beach followed, causing the equivalent of a billion dollars of damage in today’s dollars. Angelenos were fed up with such repetitive, damaging floods. These events spurred authorities finally to tame the Los Angeles River and other waterways by lining them with concrete for flood control.

As Patzert points out, these concrete channels aren’t flowing in a major way about 99% of the time.

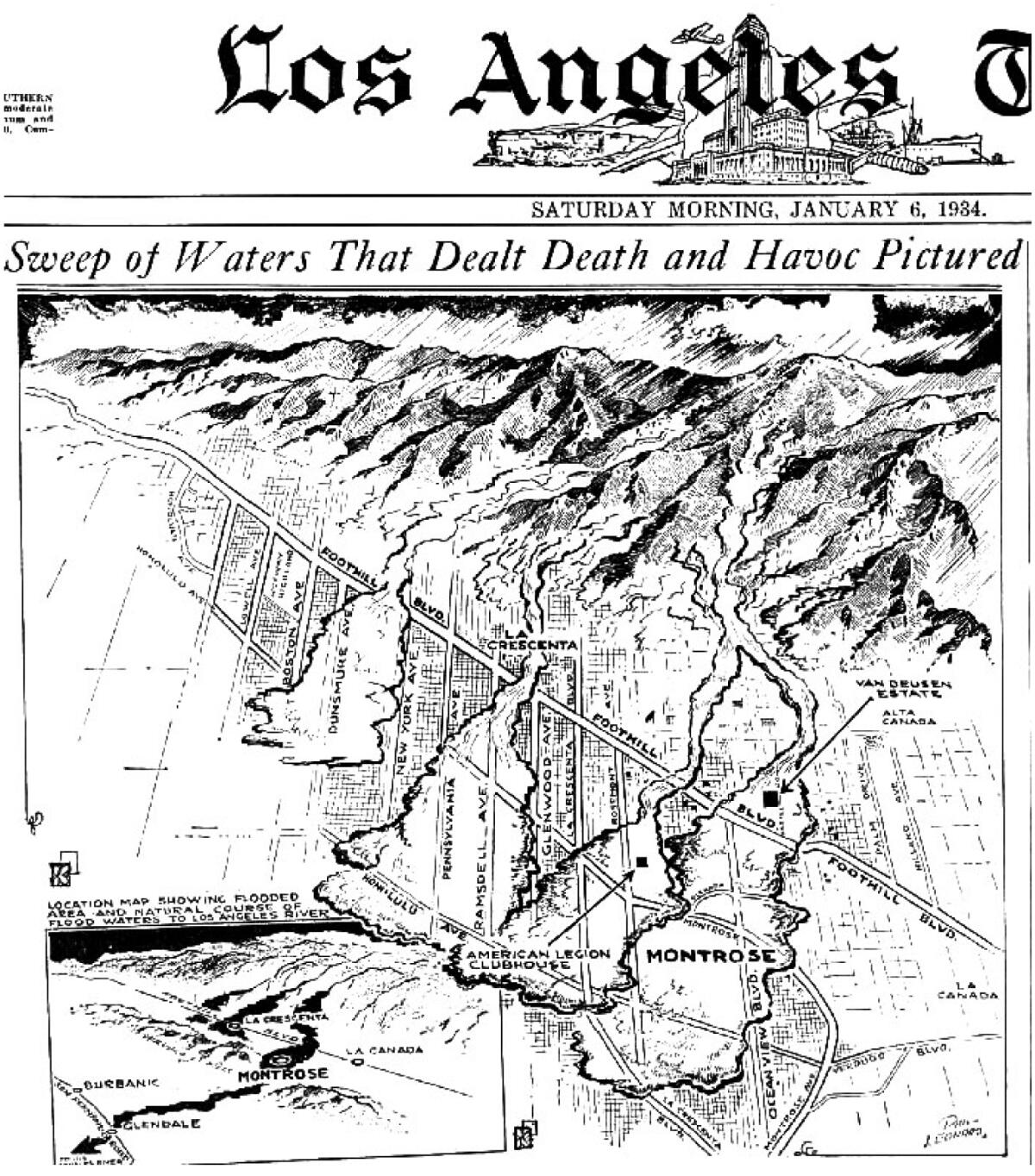

A reminder of what could happen before these waterways were made into concrete channels happened on New Year’s in 1934.

In November 1933, a fire denuded a 7.5-square-mile area in the foothills above Montrose and La Crescenta. Then, on Dec. 31, 1933, and Jan. 1, 1934, an atmospheric river storm dropped 10 to 15 inches of rain on foothill communities, and as much as 20 to 30 inches on the foothills and mountains. Downtown Los Angeles got 8.27 inches of rain, as The Times reported.

“The Montrose flood, as the calamity soon came to be called, took at least 45 lives, destroyed about 100 homes and turned the little community into a mud-filled, barren landscape, said local historian Art Cobery, who has become an expert on the catastrophe and its aftermath,” The Times reported in 2009.

Singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie memorialized the tragedy in a song about the “Los Angeles New Year’s Flood.”

Atmospheric rivers are extremely wet moisture plumes. They can drop rain on the flatlands as they come ashore, but when they lift up and over the steep and rugged coastal hills and mountains, their cargo of moisture is wrung out. This means that they’re dropping heavy rain, possibly at an intense rate, on the very areas that have been stripped of vegetation by wildfires during the previous summer and fall.

“All of this serves as a cautionary tale for those living below burn areas such as the Bobcat fire in the San Gabriel Mountains. Mudslides can’t be predicted, but they can be anticipated,” Patzert said. “The best protection for mudslides is to stay informed and evacuate when authorities issue warnings.

“Great droughts, fires, floods and mudslides after heavy rain, decade after decade. It’s a story told for thousands of years,” Patzert added. “It’s a California classic.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.