Turning to Dungeons & Dragons to escape a real-life monster — COVID-19

- Share via

For a few hours each week, Kevin Benedicto inhabits an otherworldly realm: Icewind Dale, a perilous land of tundra and frost, wizards and orcs, white dragons and crag cats. His domain is the universe of Dungeons & Dragons, the addictive tabletop role-playing game that made its debut more than four decades ago.

As dungeon master — for the uninitiated, that’s the game’s organizer and leader of the adventure — Benedicto steers his group of friends across a world conceived in their minds and limited only by their creativity and the roll of the dice. Here, they can do something they can’t in real life: defeat a monster.

“I can have a measure of control over the world, at a time when we have no control in the world,” he said.

Benedicto is a lawyer by day, but during those precious weekend hours he sits among the burgeoning number of new D&D acolytes who have turned to the game during quarantine.

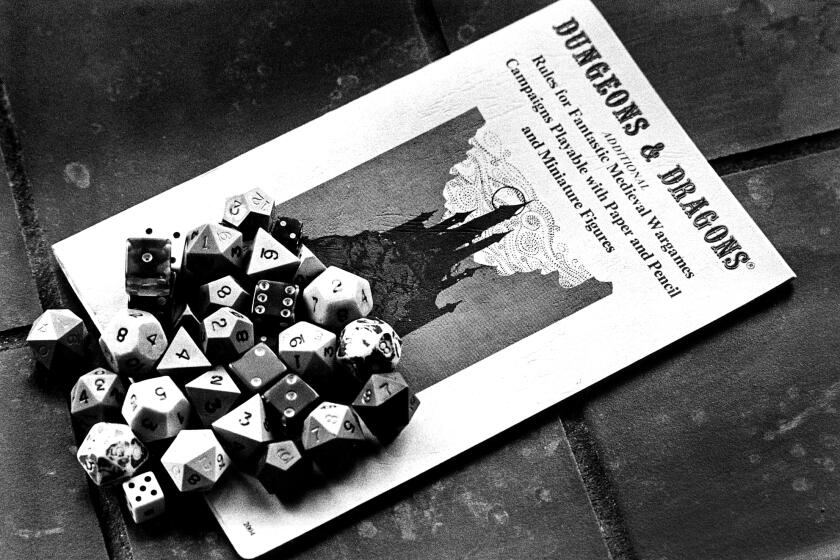

With little else to do, many players say, they now reach for the “d20,” a signature 20-sided die, gather their party and venture forth into dangerous ruins, abandoned watchtowers and hamlets filled with traders, taverns and inns that host shifty travelers.

“I suddenly had more time, since there were no more happy hours or dinners out,” said Benedicto, who in another group plays a young and preppy “dragonborn paladin” — a kind of holy fighter and spell-caster — named Aaravos Buffsprocket. “I think with the existential claustrophobia we were all feeling in the pandemic, feeling trapped in these confined spaces, escaping to a world that is boundless felt like a really good thing to do.”

Dungeons & Dragons rose from humble origins, first published in 1974 as three booklets shipped in wood-grain-colored cardboard boxes assembled by hand. The 1,000-print run sold out that year, gaining in popularity until what many assumed was its heyday in the 1980s — shortly after it was thrust into the nation’s culture wars and accused of promoting devil worship.

No D&D adventure plays out the same way. An adventure book outlines the plot of a journey, but it’s the players — through their unique characters and distinct choices — who shape the heroic quest. Each player has a set of dice with four, six and eight sides, among others, and rolls determine success or failure — whether it’s impaling an orc or hiding in the shadows from a bandit.

At a time when it feels as though society collectively rolled a “nat one” — generally, an automatic failure in the game — players largely leave their coronavirus anxieties at the door. But sometimes, like a “mind flayer,” COVID-19 invades their world. Benedicto thought he’d found the perfect new adventure book, but as he kept reading he learned that the expedition encounters a plague.

“I was like, ‘No, I think we have had enough of that,’” he said, chuckling. “Hard pass.”

Players and scholars attribute the game’s resurgent popularity not only to the longueurs of the pandemic, but also to its reemergence in pop culture — on the Netflix series “Stranger Things,” whose main characters play D&D in a basement; on the sitcom “The Big Bang Theory”; or via the host of celebrities who display their love for the game online.

Liz Schuh, head of publishing and licensing for Dungeons & Dragons, isn’t surprised by the game’s reanimated popularity. Revenue was up 35% in 2020 compared with 2019, the seventh consecutive year of growth, she said.

Many newcomers purchase starter kits packed with character sheets, a rule book, a set of dice and a story line. New dungeon masters may buy a foldable screen to hide their rolls and anything else they’d like to keep from the player-characters. Once the introductory journey ends, players pore through other adventure books for sale — or conjure an original odyssey.

“The first few days of news [of the virus] coming out globally, at the top of every hour all the alarms were going off at the company,” said Dean Bigbee, director of operations for Roll20, an online tabletop gaming platform. “The amount of new account requests were so high that the systems thought that we were under a denial-of-service attack. But they were legitimate. They were accounts from Italy, and then France, following the paths of lockdowns across the world.”

Antero Godina Garcia, an assistant professor at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education, said that interest in D&D never truly disappeared.

“It’s a 40-year phenomenon,” he said. “I think the stigma of playing it and being a nerd has dropped as ‘Lord of the Rings’ and Marvel became popular.”

The game also has become more inclusive, Garcia added, as creatives who work on updating the game have considered current sensitivities about race and stereotypes.

“Over the summer, in light of protests and the murder of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, people started looking at race representations in D&D and the ways that orcs and ‘drow’ are represented in ways that make playing the game to some inherently racist,” he said, referring to elves with dark skin often depicted as evil.

A new D&D “sourcebook” called “Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything” tackles the topic head-on, providing new rules for players who wish to diverge from the typical, high-fantasy character tropes that grant bonus points to abilities based on race.

I think with the existential claustrophobia we were all feeling in the pandemic, feeling trapped in these confined spaces, escaping to a world that is boundless felt like a really good thing to do.

— Kevin Benedicto

Traditionally, D&D players gathered in person. In 2020, virtual play rose 86%, Schuh said, aided by online platforms such as Roll20 and Fantasy Grounds.

Around 11 a.m. on a recent Sunday, Cara Palmer and friends logged into Zoom from different corners of the country for their weekly D&D session. The week before, the party had slain a horde of ogres outside the crumbling walls of a shrine.

As both a player-character and dungeon master, Palmer would set the scene for their latest encounter. Maneuvering through real-life distractions — a barking dog, a mail carrier — she pulled up a board and drew a map in black ink for the players to see. The characters observe a belfry, she explained, and a portcullis blocking their entry.

The players debated their options. Dispatch one player’s bird to conduct reconnaissance? Have someone scale the bell tower for a better vantage point?

“I don’t think the best option is to send a bear up through the roof,” one player said, laughing, referring to another character, who had morphed into an ursine form.

Palmer, who plays with friends, her boyfriend and his daughter, turned to the game for the first time in 2020, drawn by the prospect of improvising her own “Lord of the Rings”-style adventure.

For many players, she said, the characters provide the opportunity to adopt an alter ego, or a person they would never see themselves becoming. But for her, Clara the high elf cleric, is “the ideal I wish I could be.”

“What she physically does with healing is the ideal for why I wanted to be a lawyer,” the 28-year-old said. “She reminds me that what I do with my life is helping people.”

In recent years, the game has gained wider exposure through “actual play” videos and podcasts that show people playing through their adventures, including the web series “Critical Role.” On the stream, the players gather around a large table as Matthew Mercer, their dungeon master, presides.

Mercer, 38, chief creative officer of “Critical Role,” grew up playing D&D and other role-playing games, and said they helped him to come out of his shell as “a socially awkward teenager.”

“It’s such a wonderful tool to learn about yourself, to explore facets of life and your personality that otherwise you wouldn’t be comfortable doing,” he said.

On websites today, players can join an adventure with a band of strangers, or hire a dungeon master to lead a campaign. Some games are free; others might charge as much as $25 per person. The uptick in interest is part of a broader surge in tabletop role-playing games, experts say.

Mariko Green found that after moving back to California from France last year, D&D provided a way to connect with friends during lockdown.

Green belongs to three D&D groups, and one of her characters is Edamame Squirrel, the Tabaxi shadow sorcerer-rogue — a curious catlike humanoid who is “not a smart build” but fills a niche within the group, she said. Edamame Squirrel means well, but can’t help but get herself in trouble.

“We honestly really do have serious discussions,” Green said. “One friend is separating from his partner because the pandemic is so difficult, another friend struggles with things that their kids are going through. I have depression that comes and goes because of the pandemic. We have been able to seriously share about stuff.”

It’s not just newcomers who have embraced D&D in quarantine. Caity Knox and Nate Thompson have played in a nearly four-year campaign with their friends, but in 2020 went from playing once every six or so weeks to meeting every weekend.

Knox, a fashion designer whose character is a matcha-haired Druid forest gnome named Arlo Candlehall, said that playing has been “anchoring,” a tether to “what our social life used to be like before.”

Online services such as Fantasy Grounds and Roll20 provide virtual tabletops for D&D gamers to meet online and stage adventures.

Playing together has been the married couple’s main social gathering — more fun than staring at tiles of faces on a Zoom screen, said Thompson, the group’s dungeon master.

“I feel like I learn new things about people I talk to every day,” he said.

Back in a fictional shrine, Palmer and her friends had defeated a pack of orcs and recovered gold and magical loot. They debated their next move: Travel back to town? Or head up the hills to see about a necromancer who had been raising the dead?

The fellowship bantered, their biggest problems being a throng of zombies and the mechanics of towing the bell they’d stripped from the tower — but not a pandemic.

Parvini hasn’t picked up a d20 in many years, but when she does, you can find her as Lunesca, the elfin ranger.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.