Column: The deaths of Tommy Lasorda and Tom LaBonge leave a hole in the heart of the city

- Share via

In the span of several hours, Los Angeles lost two of its biggest personalities, and the city won’t be the same without them.

Former L.A. City Councilman and four-decade public servant Tom LaBonge died unexpectedly Thursday night at his home in Silver Lake at age 67. And then we all woke to the news Friday morning that Hall of Fame Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda, a World Series champion, had died at 93.

I knew LaBonge pretty well; Lasorda not so much. But for me they were both true originals, and in a sprawling metropolis that can make us feel like strangers to one another, they were rah-rah homers who made us feel connected to the place — and to each other.

“Tom LaBonge was the heart of L.A. and Tommy Lasorda was the soul of L.A.,” said Mayor Eric Garcetti, describing LaBonge as “someone who just loved everybody” and Lasorda as a fighter whose competitive spirit was made of “grit and determination.”

When Lasorda waddled out of the dugout in the heat of a big game to lay out an umpire or kick dirt, he was fighting our fight. I had only one personal encounter with him, when writing about longtime Dodger press box chef Dave Pearson, but it was memorable.

Over the course of a few hours, I watched Lasorda — who peddled SlimFast on national television — eat a plate of lasagna, a burrito, a souvenir Dodger helmet filled with ice cream and a sandwich I described as the size of a catcher’s mitt, with only slight exaggeration.

Pearson’s lasagna was almost as good as his own mother’s, Lasorda told me in his stadium office, which was cluttered with memorabilia and images of Mother Teresa, Frank Sinatra and Pope John Paul II. Lasorda, who was more interested in finishing off his ice cream than talking to me or my videographer colleague, suddenly looked up at us and asked, “Who the hell are you guys?”

The Dodger legend asked what I liked better, red wine or white. I hesitated, and he snapped at me like he barked at umpires, insisting on an answer. When I said red, he reached into his desk drawer and handed me an autographed bottle of Lasorda Montepulciano d’ Abruzzo, which said on the label: “One sip, and I am sure you will agree. It’s a … Home Run!”

You gotta love a guy who always swung for the fences.

LaBonge, if you can believe it, was always at least as pumped up as Lasorda. If you were walking down the street near the Silver Lake Reservoir, and the guy coming toward you appeared to be carrying a football, you knew who it was before you could see his face.

The solid build and impatient gait were clues, and as he got closer, the proud John Marshall High gridiron alum might cock his arm and throw you a pass.

For LaBonge, every day in L.A. was a touchdown dance.

If you caught the pass, tossed it back, then went to the supermarket, LaBonge would somehow be there ahead of you, talking to a constituent in the produce aisle about scheduling a bulky trash pickup.

And when you drove away from the store, if you came upon a minor fender bender, LaBonge would suddenly appear in his Crown Victoria to offer assistance, pulling an orange cone out of his trunk and then directing traffic.

LaBonge would show up at my door now and again because he’d seen the paper on the driveway as he walked past, and he wanted to save me the trip out to get it. Or he’d call out of the blue and offer to pick me up and go for a ride, serving as historian and tour guide.

You had to be prepared for him to hit the brakes hard if he saw an elderly resident wrestling with a trash bin. He’d get out to help, and then he’d ask what high school he or she had gone to. Once, he took me past every school he had attended as a child, then to the home where the Manson crew murdered the LaBianca family, and then to the Monastery of the Angels to get some pumpkin bread baked by cloistered nuns.

“It was like Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride,” said Garcetti, who told me LaBonge was once reprimanded by an aide for lifting a discarded toilet off a sidewalk and loading it into his car on his way to City Hall, rather than letting the streets department do the heavy lifting.

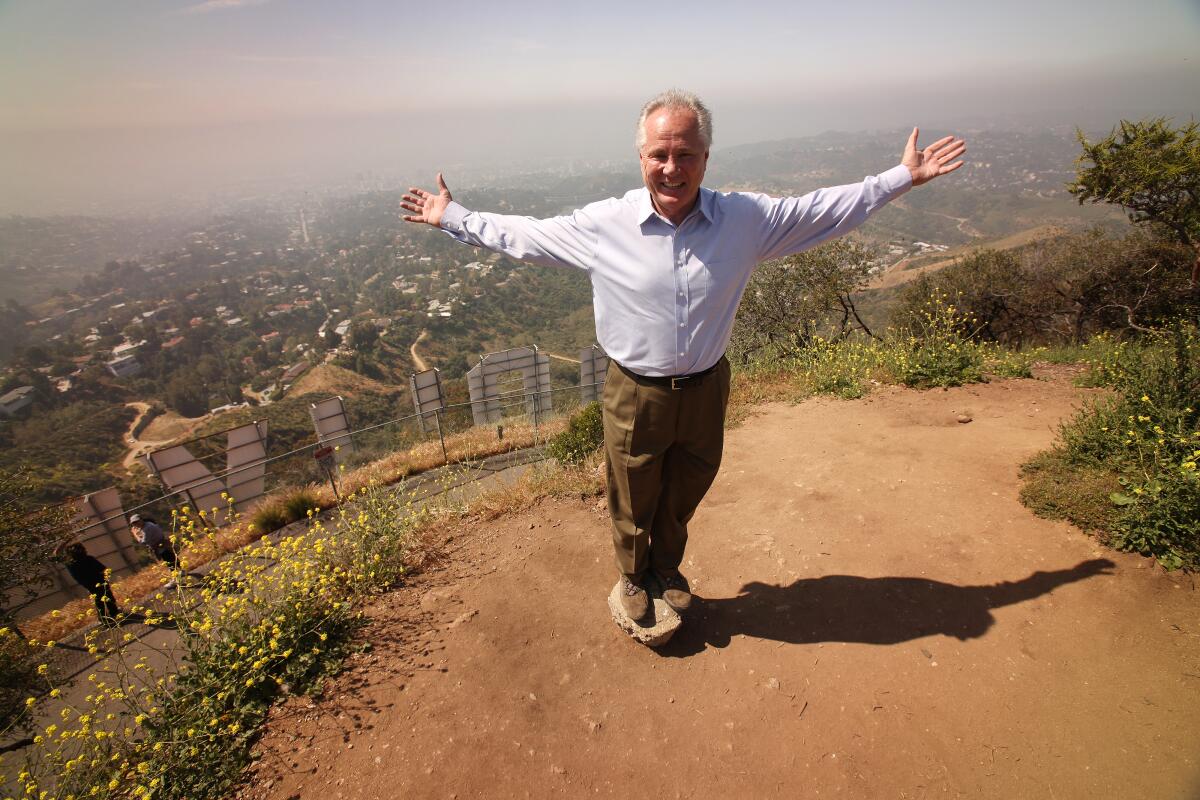

Just about every morning, when the city was asleep, LaBonge would go up to the Griffith Observatory and hike the hills, every inch of which he was familiar with. He insisted I experience the glory of the park at sunrise, so I went up there with him one day and quickly found myself struggling to keep up. He hoofed up and down ravines like a goat, talking all the while about the foliage or wildlife or historic park fires, or he’d hit me with pop quizzes about local history.

At the top of Mt. Hollywood on our long hike, with me huffing and puffing, he threw me the football, thrust his hands up and yelled, “Touchdown!”

LaBonge, like any elected official, was not loved by all — making enemies as well as friends is built into a councilman’s job. He’d get beaten up by Hollywood residents ticked off about streets jammed by visitors to the Hollywood sign, for instance, and a recurring rap was that he wasn’t exactly a legislative visionary.

LaBonge would argue that he did have a vision and a mission, an old-fashioned one, which was to be out and about in the neighborhoods he served, from Koreatown to Los Feliz to Hollywood and the Valley, to get to know the people and try to answer their needs, even if at times he couldn’t please everyone.

I ticked LaBonge off one time when I wrote about things getting bottled up in the city bureaucracy. He suggested we trade places, with me serving as councilman for a day and him taking over my column.

I spent a day with him to feel it out, and even made a couple of speeches at different events, but I knew I didn’t have the skills, the patience or the energy for a job much harder than my own. LaBonge never took over my laptop but told me that if he were a columnist, he’d specialize in everything good about Los Angeles and its people.

Though LaBonge left City Hall four years ago, Garcetti said, he never really retired.

“The day he died he was bringing water to workers next door, moving cars to help construction trucks get in place, and it was his favorite day of the week: trash day. So he was moving his neighbors’ trash bins in and out,” said Garcetti, who went to LaBonge’s home Thursday night when he heard the news of his death, and spent several hours there with LaBonge’s wife, Brigid, his daughter, Mary-Cate LaBonge, and his son, Charles.

In Tom LaBonge’s mind, the city was the center of the universe, with more niceties than negatives, a place full of hope.

In Tommy Lasorda’s mind, the Dodgers were always in the game, fighting to win a pennant for L.A.

Touchdown Tom and home run Tommy delivered, and they will be missed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.