Santa Monica politics upended by pandemic, George Floyd protests and economic woes

- Share via

Many of the forces that have shaken America in 2020 — the pandemic, a sharp economic downturn, rising inequities and the protests fueled by the killing of George Floyd — are also upending politics in Santa Monica.

In the last year, the famously liberal city, sometimes seen as a bellwether in local government, has dealt with a series of dramas culminating in a profound shift in power that will likely reshape Santa Monica for years to come.

For the record:

2:56 p.m. Dec. 21, 2020This article incorrectly states that Oscar de la Torre resigned from the Santa Monica-Malibu Board of Education after being elected to the Santa Monica City Council. De la Torre has not resigned from the school board, although school district officials believe the two offices are incompatible and have advertised the board vacancy.

12:05 p.m. Dec. 20, 2020An earlier version of this article said that Santa Monica’s operating budget shrank nearly 24% this year, with a projected deficit of $102 million. The budget is balanced after being cut by nearly 24% to resolve the projected deficit.

First the city manager, then the police chief, departed amid withering criticism and a yawning budget deficit. The City Council elections attracted a slate of newcomers with a platform of slowing development in the wealthy oceanside community.

With that came massive spending from local political action committees, text messages from candidates pinging on voters’ phones and an all-out push from the city’s establishment to hang on to power.

On Nov. 3, residents voted in three of the four newcomers — a historic shift for a city where elected office has been contingent on incumbency and the support of a single organization, Santa Monicans for Renters’ Rights.

“It’s an epic blowback,” said Oscar de la Torre, 49, who is founder of the Pico Youth & Family Center and resigned his seat on the school board to join the City Council. “We were outgunned, outspent … you name it, we were up against the entire establishment and we beat them in a pretty powerful way.”

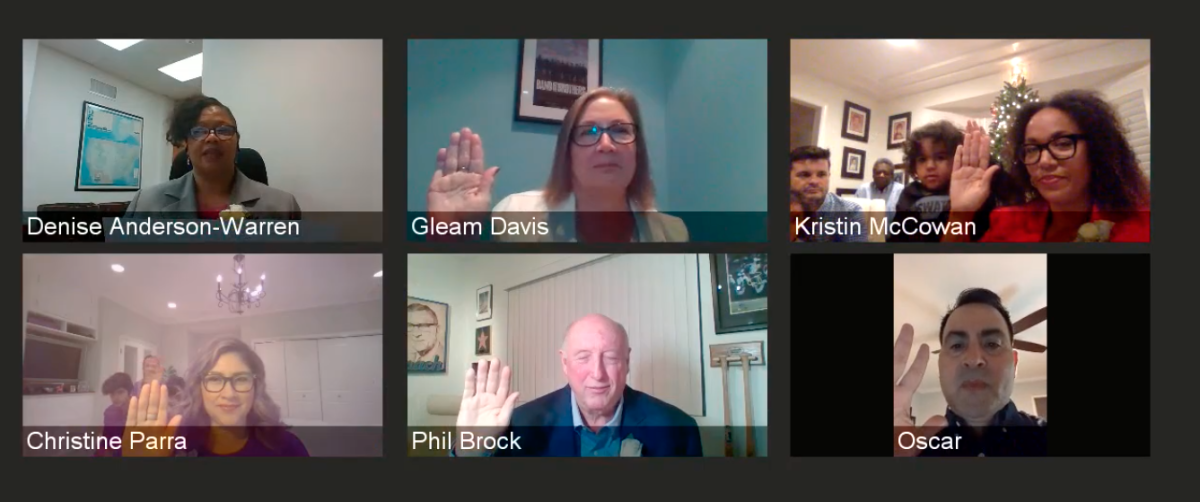

De la Torre and the two other winning members of the slate, Phil Brock and Christine Parra, are a powerful minority on the seven-person council after being sworn in Dec. 8.

They will have a significant hand in managing an enormous budget shortfall caused by declining tax revenues as coronavirus restrictions devastate local businesses.

They must select a new city manager — the executive who runs the government day to day, while most council members maintain other careers.

They must repair public trust in a Police Department that failed to protect some businesses during street unrest in May while arresting hundreds of peaceful protesters and firing rubber bullets into crowds.

Homelessness, a perennial problem in the city, prompts a constant barrage of complaints from residents, with no easy solutions.

And the new council members’ slow growth mantra will be put to the test as they try to put the brakes on commercial development yet fulfill a campaign promise of creating more affordable housing in a city where 72% of residents are renters and real estate prices are sky high.

They have already made an impact. In their second council meeting last week, they joined with Mayor Sue Himmelrich to end negotiations with the developer of the controversial Plaza project.

“I have nothing against progress. But I want our change to be in concert with the residents’ desires to have a low-rise, diverse, comfortable beachside city,” said Brock, 66, a talent manager active in community organizations. “We don’t want to become Miami Beach. We don’t want to become an extension of downtown Los Angeles. We want to be uniquely Santa Monica.”

With 22 council candidates on the same ballot as the presidential election, turnout was 79% in the city of 90,000. Four seats went to the top vote-getters: Brock came in first with more than 19,000 votes, followed by incumbent Gleam Davis, Parra and De la Torre. Kristin McCowan ran unopposed for the two remaining years on a seat she filled when a council member resigned.

Incumbents Terry O’Day, Ted Winterer and Ana Maria Jara lost, as did a member of the new slate, Mario Fonda-Bonardi.

Himmelrich and Kevin McKeown did not run in this election and remain on the council.

The new council will be the most racially diverse in Santa Monica history, according to city spokeswoman Constance Farrell. De la Torre and Parra are Latino, and McCowan is Black. Davis’ biological father is Mexican American, and she was adopted at birth by white parents.

Brock, De la Torre and McCowan all grew up in Santa Monica. In a shift away from tonier parts of the city, De la Torre, McCowan and Parra are residents of the historically Black neighborhood of Pico.

“It’s very simple,” said Parra, 48, who is the emergency preparedness coordinator for Culver City. “The community felt unsafe and really felt unheard, and they were looking for someone — anyone — that would hear them and represent them and be them up on that dais.”

In Santa Monica, city politics involves fairly big money.

While individual candidates raised cash, the biggest financial push came from a PAC called Santa Monica Forward, which spent more than $196,000 on behalf of Davis, McCowan and the three losing incumbents, according to the most recent campaign finance disclosures.

The committee’s website states that it is in favor of “a thriving local economy,” more affordable housing and a “cleaner and greener city. “

For more than 30 years, a majority of the City Council has been endorsed by Santa Monicans for Renters’ Rights, according to the group’s co-founder and co-chair, Denny Zane.

This year, Davis and McCowan were the only winning candidates backed by the organization, which primarily advocates for tenants and promotes affordable housing. With Himmelrich and McKeown, who were elected in 2018, SMRR-supported candidates maintain a narrow 4-3 edge on the council.

Though politically influential, the renters’ rights group was not a large player financially, spending nearly $44,000 spread out among council, school board and other races.

The only PAC to spend all its money on the newcomers was Santa Monicans for Change 2020, with about $18,000. Another local group, Santa Monica Coalition for a Livable City, advocated for the newcomers but did not raise money.

Despite all the cash at their disposal, Santa Monica Forward leaders had a hard time developing effective campaign techniques, with the pandemic limiting their ability to canvas door to door, co-chair Abby Arnold said.

As the council campaign was getting underway, city leaders were struggling with budget and policing issues.

Amid heated debates about cutting city personnel and community programs, City Manager Rick Cole resigned in April. The city has since eliminated more than 400 positions. This year’s operating budget shrank nearly 24% to resolve a projected deficit of $102 million.

“It’s easy to be critical. What’s difficult is to find common answers to the real challenges facing communities,” Cole said. “The community will suffer if people don’t put aside the divisions of this election and work together for the common good.”

A pivotal moment that turned many residents against city leaders came on May 31, when the racial justice protests that were sweeping the country and the region came to Santa Monica.

McKeown and then-police Chief Cynthia Renaud took a knee in solidarity with protesters. But that did not erase the harsh tactics that police officers had used. Others lambasted Renaud for allowing people to break into stores and steal merchandise without a police officer in sight.

Council members tried to distance themselves from the no-win situation, saying it was not within their power to give the police chief orders that day. They promised to do a post-mortem review, form a Racial Equity Committee and create a commission to oversee the Police Department. Renaud retired in October, after a petition calling for her removal attracted more than 66,000 signatures.

Brock, who participated in a peaceful march down Ocean Avenue, said the Police Department should have been better prepared for civil unrest, and the City Council did not do enough to reach out to business owners whose stores were damaged.

Known as much for its outdoor Third Street Promenade mall as its old-school pier and Ferris wheel, Santa Monica has long wrestled with how much revenue-generating commercial development to allow without sacrificing its beachy, slightly bohemian character.

Bobby Shriver, who was a councilman and mayor from 2004 to 2012, looks back wistfully at the independent bookstores and coffee shops that have given way to national chains.

“People appear to have just gotten overwhelmed by the volume of things that have been approved,” said Shriver, who now lives in Wyoming. “You could read this vote as a scream by the residents to put a moratorium on this, or ‘Stop it, we’re going to lose the character of our community.’”

De la Torre, Brock and Parra campaigned against the Plaza project, which would be a hotel and workspace on what is now mostly occupied by a parking lot at the busy intersection of 4th Street and Arizona Avenue.

The lot, which is public land, should be used either for a park or apartments, the newcomers say.

Tuesday’s 4-3 vote stopped talks with the developer, and the council will eventually decide what to do with the property.

The newcomers say the city needs more affordable housing. But they plan to challenge what Brock calls an “unrealistic” goal set by state and regional authorities to build almost 9,000 new housing units, including about 70% for low-income households, by the end of 2029.

Parra said the numbers don’t add up. Santa Monica already has thousands of vacant units that could be used for affordable housing, while lacking the infrastructure, such as water and sewer lines, to support so much new construction, she said.

Richard Orton, a retired graphic designer who has lived in Santa Monica for 50 years, supported the newcomers slate.

For nearly a month leading up to the election, he helped the candidates by designing fliers advocating for “new blood in the City Council.”

“You talk to the City Council, but you get the feeling that they’re kind of indifferent to you,” said Orton, who is in his 70s. “They never vote in your direction. They always seem to vote for the developer.”

But some establishment politicians question whether the election amounted to a significant mandate or was mostly emotional fallout from an unprecedented year.

“I think the effect of the COVID pandemic made for an electorate that was looking to send a message,” said Davis, who has served on the council since 2009. “Not sure I know what the message was, other than, ‘We’re unhappy.’”

Times staff writer Maloy Moore contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.