- Share via

Before we started getting sick, we had time — time to meet, to talk and gather, to sing, to cheer and roar. The minutes in the hour, the days in the week, were luxuries no one could steal from us.

2020 was to be nothing like 2019, with its mosque attacks in New Zealand and a fire in Notre Dame, an investigation into the 2016 election and the futile calls for order. We turned the calendar page, and the promise of a new year lay before us.

We had time for everything, and then we had time for nothing — nothing except the virus.

Patricia Dowd of San Jose was 57. She watched her diet, exercised and took no medication, and in early February, she was the first known COVID-19 fatality in the nation.

How quickly then the novel coronavirus mocked our assumptions and challenged our simplest routines. A trip to the market, a drive to drop off the kids at school brought the specter of unfamiliar peril. It left some of us struggling to breathe, others trying to help and most hoping to keep their distance.

Forgotten were the fires that had ravaged Australia, an assassination in Baghdad. Impeachment and acquittal of the president belonged to the past. The theatrics after the State of the Union, anxiety over Brexit, relegated to another time and place.

No past, no future — all we had was the moment before us.

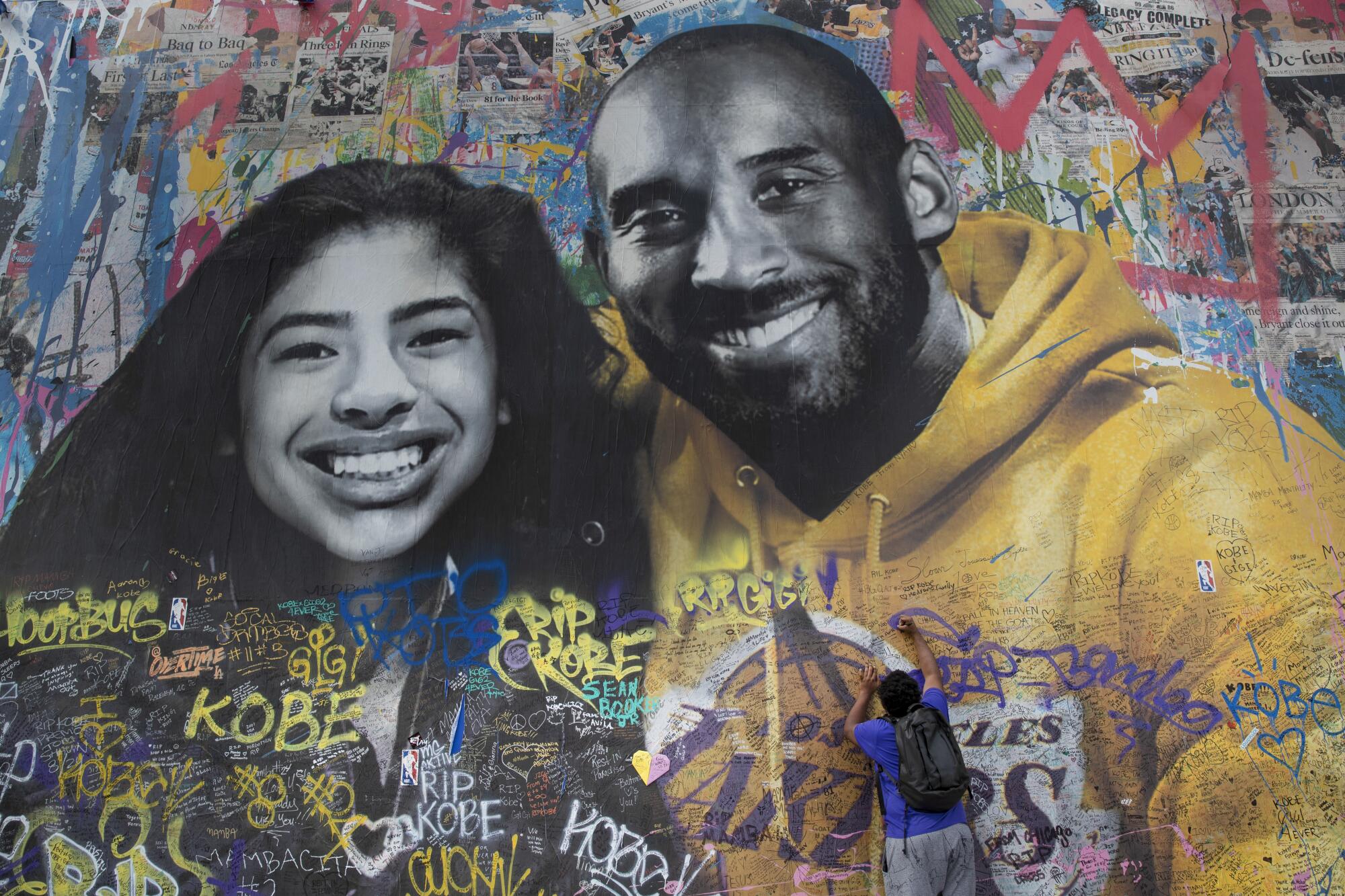

Only the loss in January of Kobe, 13-year-old Gianna and seven others in a fiery crash on a foggy hillside near Calabasas still pulled at our hearts, a premonition of grief that lay ahead.

Cities fell quiet. We stared out windows and measured lives in modest increments. Weddings were postponed, holidays disappeared.

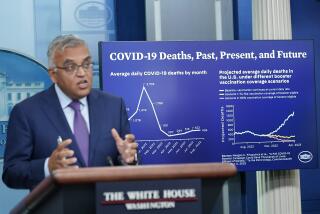

Politicians stood beside doctors. They admonished. They consoled, and the virus, lifted by the slightest breeze, flouted their words.

We grew confused. Neighbors in Culver City donned masks. Protesters in Huntington Beach decried their use. Stay-at-home orders were issued in March, and by August, tens of thousands of motorcycle enthusiasts filled the streets of Sturgis, S.D., rallying for themselves.

The Year in Review

“I don’t think there was nothing that was going to stop me,” said one rider, who later fell ill.

Two Americas were on display. For some, caution meant fear and repression. For others, it was a sign of respect. We became armchair experts in economics and public health, and we argued as we have about everything else.

A nonessential class emerged, buoyed by an essential class who rang doorbells with deliveries, stocked shelves with food, carried our mail and attended to the sick and dying.

We searched for words to describe this moment. Dystopian, post-apocalyptic came to mind as if we were living a Hollywood dream run amok. Jackals roamed Tel Aviv, monkeys marauded through a village in Thailand, and an offshore algae bloom lighted the midnight surf neon blue.

But the suffering was too grim to be scripted. Refrigerated trucks for the dead pulled into the parking lot for a hospital in Queens, where 13 patients died in 24 hours.

Many lost all that they had. By the end of April, more than 30 million had filed for unemployment, 23 million were at risk for evictions, and the numbers kept rising. By mid-December, the United States had counted more than 16.1 million coronavirus cases and over 290,000 deaths.

In addition to this terrible accounting, the virus exploited our weaknesses. Inadequate healthcare, inadequate housing, inadequate working conditions and food deserts had left Black, brown and Indigenous communities in mourning. For every white person who died of COVID-19, people of color buried three or more.

The tragedy was clear: We could probe the universe and witness stars being born in a distant galaxy. We could find moments of grace: a daffodil placed on body bags, a porch concert in Pasadena, arias rising from the balconies of Rome, the streets of San Diego, the hills of Silver Lake.

But we could do little to alter the course of this disease.

No wonder then that we began to lose patience. Tired of lockdowns, tired of restrictions, we gave this tiredness a name: pandemic fatigue. We knew we were running out of time. Some of us had to take action.

When George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis on May 25, a coalition of the concerned — activists, protesters, families and friends — took to the streets. Eight minutes, 46 seconds became a rallying cry for the reckoning ahead.

They chanted the names of Floyd, of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor. They washed their eyes of tear gas. They salved the sting of rubber bullets. They did not disperse.

From Washington, D.C., to Portland, Ore., Minneapolis to Los Angeles, they shouted their demands: Defund the police, ban chokeholds, release body cam footage, end cash bail, prohibit stop-and-frisk.

And amid these cries, we caught a fleeting glimpse of the moral universe’s long arc in tributes and farewells to Rep. John Lewis and Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

We counted a few gains.

NASCAR banned the Stars and Bars. Mississippi redesigned its flag. Quaker Oats retired Aunt Jemima, allowing her real-life forebear, Nancy Green, to step out of the shadows of a minstrel past. The attorney general of Mississippi declined to prosecute Curtis Flowers for a seventh time, and Merriam-Webster updated an entry:

Racism, a noun (rac ism \ ‘rā- , si-zəm also – , shi - \), is not just a belief in the supremacy of one race over another. It is oppression, an unjust or cruel exercise of authority or power, based on race, resulting in social, economic and political inequity.

But not everything could be rewritten. As spring turned to summer, summer sparked heat, fires, smog and an endless succession of hurricanes that battered our weary coasts.

Centuries of neglect, years of indifference had caught up with us. Once unable to imagine this warming future, we worried that we had squandered the time when we had it and were left now to crank up the AC or take to higher ground.

We sought diversion as we do so well. Houseplants, TikTok, “Jerusalema,” waacking, the Lakers and Dodgers helped. But the pandemic was relentless.

“I’m feeling great!” the president declared from the White House after falling ill and being treated for COVID-19. If only we felt the same.

Eleven days earlier, we had tuned into either “a hot mess, inside a dumpster fire, inside a train wreck” or, more simply, “a disgrace,” as one television host struggled to describe the first debate between President Trump and Joe Biden.

Soon, however, November was upon us, and as the darkest winter drew near, nearly 160 million found their way through the gloom. They mailed their ballots. They stood in line. They confirmed their faith in the promise of a more perfect union.

When the counting was over, the most important election in our history was declared the most secure. Trump got 74 million votes, but Biden and Kamala Harris, with 81 million votes, will set a new course for America, and maybe they will have time and, with a vaccine, hope.

After four years of derision and marginalization, science was vindicated. Laboratories found answers in less than 11 months to questions that often take years of study, and we are poised to benefit from that research and commitment.

Time, we all know, is a measurement of the movement of our planet in space, but in 2020, it became so much more.

In days, weeks and months, it measured how long since most of us last embraced our family, laughed with friends, sang in choirs or cheered our teams. And one day it will mark our reunions.

Time is the promise of both an end and a beginning, and as this year concludes, it leaves us once again with hope for what lies ahead.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.