Vietnamese immigrant families hash out political differences, even without a common Thanksgiving table

- Share via

Last month, Kim Nguyen gathered with her extended family over Vietnamese crab soup to celebrate her grandmother’s birthday.

As her uncles expressed support for President Trump, her younger cousins shouted their disagreement from another room.

Nguyen, 29, a Garden Grove city councilwoman, once stayed silent when her elders expressed political views she disagreed with. This year, amid the coronavirus outbreak, racial justice protests and a highly contentious presidential election, Nguyen has become bolder about speaking out.

When Black Lives Matter protesters filled the street in front of her father’s house, she tried to make him understand the obstacles that Black Americans face. When Vietnamese-language media outlets disparaged her support for affirmative action, she doubled down and explained her beliefs to her parents.

As the chasm between red and blue America grows, families across the country are politically divided. For Vietnamese immigrants, the gap can be especially profound.

Many in the older generation are vehemently anti-communist, making them a sympathetic audience to Trump’s tough stances on China. They may get their news exclusively from ethnic media, which can lean toward a single narrative without a variety of perspectives. As refugees who built a new life after coming to this country with nothing, they can be skeptical of efforts to prop up disadvantaged groups.

Meanwhile, some young Vietnamese Americans have embraced the progressive movement that sent protesters into the streets over the summer and that has emboldened many people to have difficult conversations with family members about topics they once avoided.

It can feel like the two sides are speaking different languages. And sometimes they are, cobbling together Vietnamese and English to discuss high-level concepts — how do you say “affirmative action” in Vietnamese?

Because of the surge in coronavirus cases, Nguyen and her family were not planning to get together for their usual bicultural Thanksgiving meal of spring rolls, turkey and mashed potatoes.

But even without family gatherings, the holiday weekend is a time for people to take stock of their relationships and the issues they care about most — especially if those things clash.

“It helped to learn where they were coming from, and while we didn’t always come to a resolution, it was a step in the right direction,” Nguyen said.

While the pandemic is keeping some people apart, it is drawing others closer as nuclear families hunker down together, leaving plenty of time for discussions to spiral out of control or for long-simmering conflicts to finally be resolved.

Heidi Nguyen, a Newport Beach family counselor whose clients include many Vietnamese Americans, said her business has been booming in recent months.

Cultural and language differences make immigrant families especially vulnerable to painful generation gaps, which have been intensified by the stresses of the pandemic.

“Oftentimes, the younger generation doesn’t know how to communicate with their parents, and the kids may harbor negative feelings that lead to anxiety or depression,” Nguyen said. “My main advice for family members is to build empathy and understanding for the other side before communicating.”

Language barriers can limit debate and result in silent frustration.

Cindy Nguyen, a junior at Westminster High School, understands enough Vietnamese to know that she disagrees with her parents’ political beliefs.

But she is not fluent enough in the language to fight back.

“I know what they’re saying in Viet, but I can’t always respond to them,” said Cindy, 16. “Like I can’t think of the word ‘equality’ on the spot.”

According to a national survey released in September by AAPI Data, APIA Vote and Asian Americans Advancing Justice, Vietnamese Americans were the only Asian subgroup that favored Trump over Joe Biden, 48% to 36%.

Some older Vietnamese immigrants were probably swayed by negative associations with people purported to be communist or socialist, said Karthick Ramakrishnan, a co-author of the survey who is a professor of political science and public policy at UC Riverside.

“In this election, a lot of the rhetoric portrayed Biden as a socialist, even though it’s not accurate to label him that way, and it resonated with the first generation’s strong anti-communist views,” Ramakrishnan said.

But the survey also found that Vietnamese Americans, regardless of age, tend to lean liberal on issues such as social safety nets, healthcare, gun control and environmental protection.

Thai Viet Phan, who successfully ran for a seat on the Santa Ana City Council this fall, learned firsthand how powerful an allegation of communist associations can be.

In October, her parents were shocked to receive an attack mailer comparing her to communist leader Ho Chi Minh.

“It was traumatizing for my family to see that,” said Phan, who will be Santa Ana’s first Vietnamese American council member. “It was hard to explain to her and our neighbors that they were literally making things up.”

Phan, 32, sometimes educates her parents with information from news sources other than Vietnamese newspapers and television. She and her extended family argue intensely over issues such as Obamacare and deportations — discussions that would not take place this Thanksgiving, with their gathering canceled because of COVID-19.

Trung Ta, 67, is a Democrat who agrees with his son, Viet Ta, on most political issues.

But the retired aerospace project manager was troubled by his son’s support of Sen. Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist.

“I do understand that word is jarring with our community’s history with communism, but I don’t believe Bernie Sanders is a communist,” said Viet Ta, 33. “This was the most fiery argument we had.”

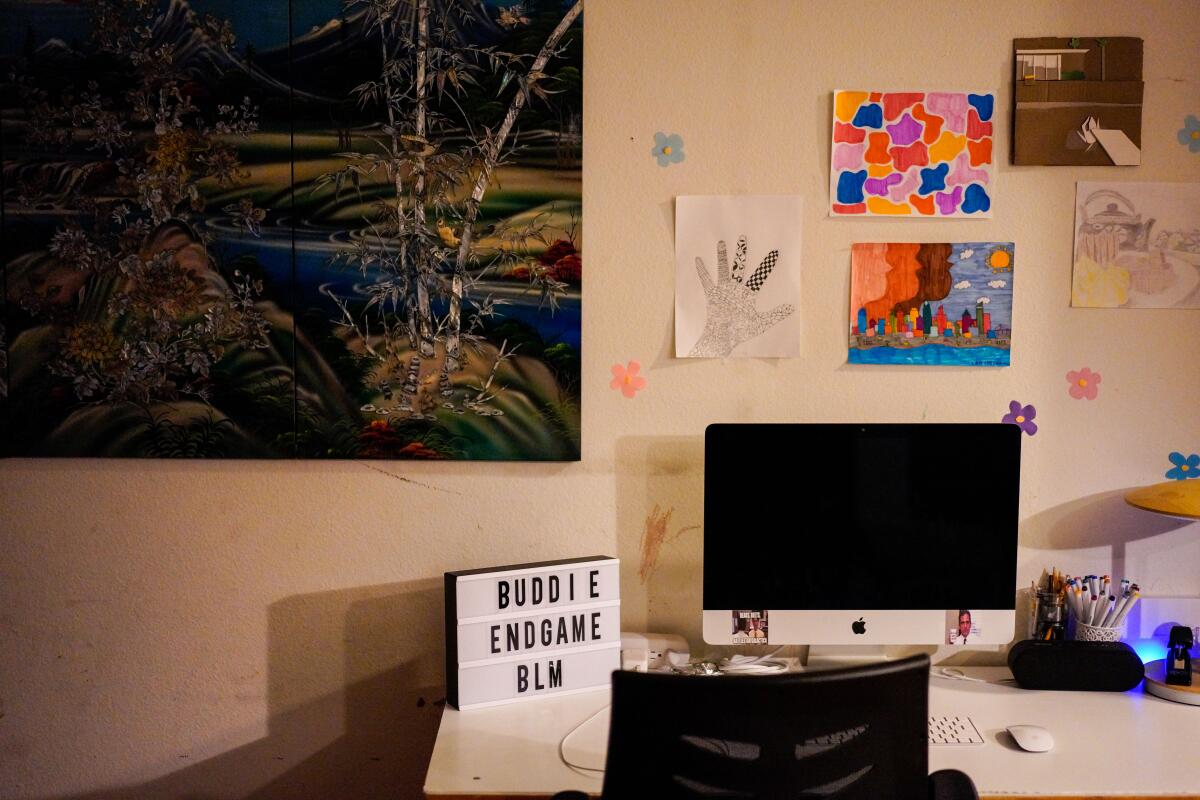

When Lan-Chi Nguyen Cantuba put a Black Lives Matter sign on her desk, her father asked her to take it down.

Lan-Chi, 16, put the sign up again two days later — a silent war that eventually turned into a shouting match between father and daughter.

“It makes me uncomfortable when these issues come up. It’s really stressful to be in a household that doesn’t share the same beliefs,” Lan-Chi said. “It’s unsettling that my father thinks so differently, but I still love him.”

Lan-Chi’s mother came to the U.S. from Vietnam in 1991. Her father, Cesar Cantuba, is from the Philippines, but the clashes with his daughter are similar to those experienced by Vietnamese parents.

Cantuba’s conservative beliefs, informed by his Christianity and by-the-bootstraps immigrant success story, seemed incompatible with his daughter’s progressivism.

But several weeks ago, the Nguyen Cantubas sat down at the dining table and hashed out their issues, with the goal of reconciliation.

On Thanksgiving weekend, the discussion could veer into politics and grow heated once again. But Cantuba, a 58-year-old construction manager, hopes the work they have put into their communication skills will pay off.

“We can differ in beliefs, but family is family,” Cantuba said. “I will still love and die for them if I have to.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.