With push for progressive D.A.s, elected prosecutors feel the pressure of a changing profession

- Share via

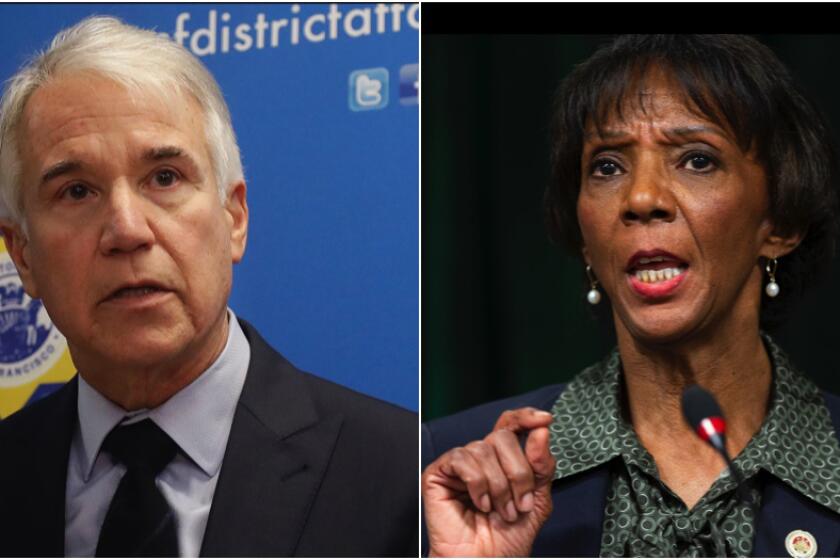

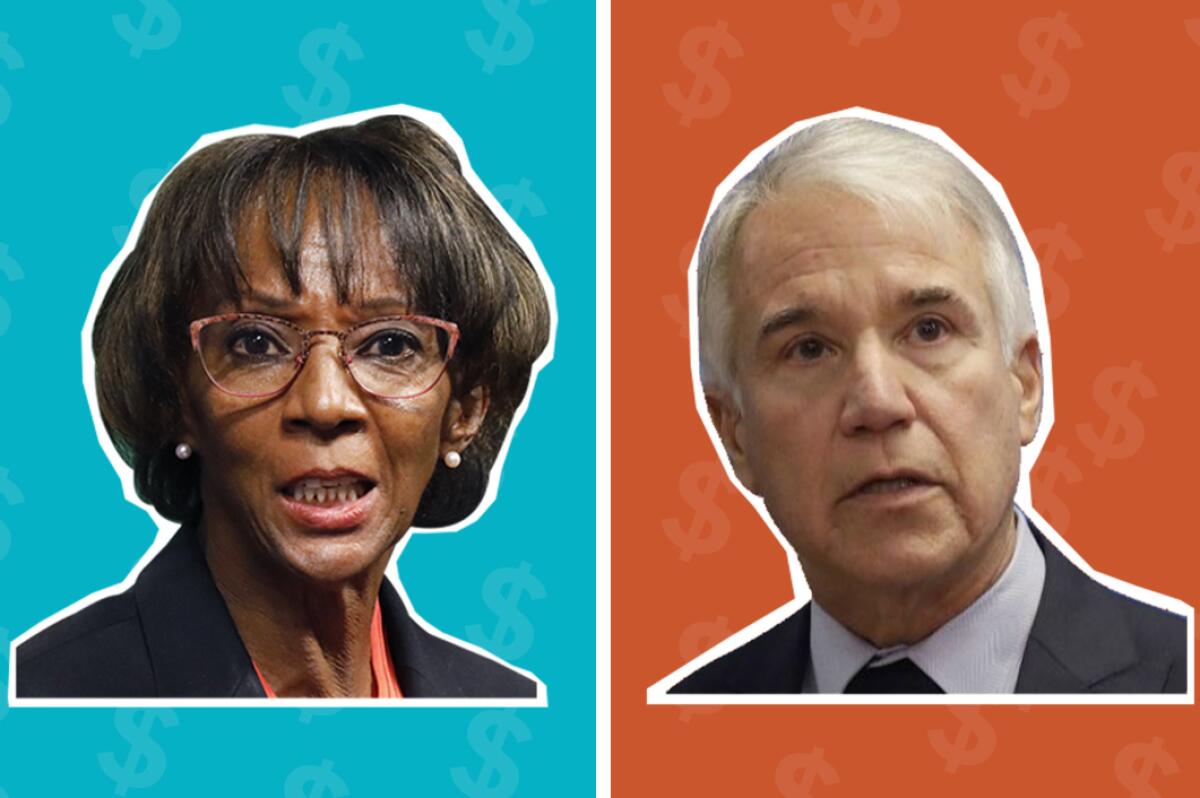

When Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey began her fight against challenger George Gascón, her strategy to fend him off seemed clear: attack the purported reformer as weak on crime, while touting her own record on public safety.

That classic approach seemed to work during a March primary that saw Gascón, the former San Francisco district attorney, finish 20 points behind Lacey, narrowly forcing a runoff in November. But after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd in May, sparking national protests against police brutality and what some see as systemic racism in the criminal justice system, the tenor of the race shifted.

Suddenly, crime statistics seemed an inadequate measure of a prosecutor’s worth. Amidst calls from protesters for her to step down, Lacey changed her attacks on Gascón — questioning his credentials as a reformer.

Once content to slam him for property crime surges in San Francisco, Lacey instead tore into Gascón’s record of not prosecuting police in fatal force cases, even though she’s been routinely criticized on the same issue during her eight years in office.

The battle between Lacey and Gascón is both a microcosm of — and perhaps now the most important battleground in — a national struggle over the future of how prosecutors operate in the U.S. As criminal justice reform has moved from a back-burner issue to the forefront of American politics, advocates have increasingly targeted elected district attorneys as a weak link in efforts to cultivate a more equal justice system and hold police and public officials accountable.

The November contest between Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey and former San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascón to oversee the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office has been framed as a test of appetites for criminal justice reform.

“We have gone from a point where many prosecutors could take for granted that they were going to be reelected without talking to the community,” said Alissa Heydari, deputy director for the Institute for Innovation in Prosecution at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. “Now prosecutors are very much in the spotlight.”

A combination of victories by nearly a dozen progressive candidates in Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco and other locales, and rising public anger over police misconduct, has given momentum to an effort that only a few years ago seemed quixotic. Some contend that even prosecutors not up for reelection are embracing reform, or at least reform rhetoric, in a bid to retain popularity and preempt challenges similar to Gascón’s.

Prosecutors traditionally have been close allies with local law enforcement. But ideas such as lowering incarceration rates, ending cash bail and diverting low-level offenders from the criminal justice system have become common themes even for mainstream prosecutors, evidence of a new mindset in a profession that once was mostly centered on conviction rates and police support.

“It’s a cat that’s out of the bag,” said Chris Lazare, an organizing director with the Real Justice political action committee, one of the most prominent groups pushing for reform-minded district attorneys. “It’s slow for sure, but it’s working.”

That shift started in 2016 when criminal justice reform advocates began fundraising and organizing on behalf of local challengers, bringing money and expertise to sleepy races where often the only big cash came from law enforcement unions.

In Philadelphia, an upset win by then-civil rights attorney Larry Krasner put a defense lawyer in power in a city with some of the highest per capita incarceration rates in the country. At the same time, Black Lives Matter and other community groups began targeting district attorneys with protests and bad publicity after controversial police killings of Black and Latino people across the country.

Since Krasner’s win, Lazare said the Real Justice PAC has helped the campaigns of at least 35 candidates for district attorney, including Chesa Boudin in San Francisco, Joe Gonzales in the county covering San Antonio and Kim Foxx in Cook County, Ill., the second-largest prosecutor’s office in the country, which encompasses Chicago.

In Miami, former assistant state attorney Melba Pearson fell short in her bid to unseat veteran prosecutor Katherine Fernandez-Rundle this summer. But shortly after the election, Fernandez-Rundle said she would convene a task force of researchers, activists and law enforcement leaders to address issues of inequality in the criminal justice system.

While Pearson says she has little hope Fernandez-Rundle will back away from her more traditional tough-on-crime approach, she does think contests like the one in Los Angeles are putting incumbent prosecutors on notice that a significant segment of their constituencies wants change.

“There will be some instances where a well-funded challenger will scare the bejesus out of an elected [prosecutor],” said Pearson, who now serves as the director of policy and programs at Florida International University’s Center for the Administration of Justice. “You’re thinking about the long game and you’re thinking about your future, so you may be more willing to make some of the changes and be more responsive to the public outcry.”

Observers have noticed Lacey moving left on some issues due to the looming threat of Gascón’s candidacy. She dismissed tens of thousands of marijuana convictions in February, about two months after Gascón entered the race and more than a year after he launched a similar initiative in San Francisco. But overall, she has rejected most ideas central to the progressive movement, such as abolishing the death penalty.

Some criminal justice advocates contend the pressure to shift left is being felt even in places where the incumbent is not on the ballot.

Cephus Johnson, a reform advocate in Oakland, said he believes such concerns influenced Alameda County Dist. Atty. Nancy O’Malley’s recent decision to reopen the investigation of the shooting of Johnson’s nephew, Oscar Grant, by Bay Area Rapid Transit Police in 2009. O’Malley handily bested challenger Pamela Price in 2018, during an election cycle in which a number of progressive contenders tried, but failed, to upset entrenched prosecutors in California.

Grant’s case was one of the first times an officer, Johannes Mehserle, was charged in an on-duty killing. But Grant’s family has long contended that Mehserle’s partner, Anthony Pirone, who knelt on Grant’s neck, should also have faced charges. Johnson said that during a recent meeting that O’Malley promised to review Pirone’s participation.

O’Malley has disputed that politics played into the Grant case, saying in a statement that, “My role as the elected district attorney remains the same as it has been since I took office. I am responsive to the community I serve.”

But Johnson said he has noticed a change in prosecutors’ attitudes in the decade he has worked on criminal justice reforms.

“District attorneys have now looked at the possibility for them and their political careers being damaged for failures to hold these officers accountable,” said Johnson. Passage last year of a new California law lowering the threshold for officers to be charged in on-duty killings may also put more pressure on prosecutors, he said.

Some retired prosecutors and law enforcement experts, meanwhile, contend ideas espoused by some progressive challengers may harm public safety. Steve Cooley, who served three terms as L.A. County’s top prosecutor before Lacey, said progressive mega-donors have boosted candidates he considers unqualified.

“They are able to come in and put someone in there who ordinarily wouldn’t stand a chance in hell,” Cooley said.

Even as they have begun to tap funding from their own moneyed interests, Gascón and other progressive prosecutors have called on their peers to cease taking union contributions, arguing doing so creates a conflict of interest when considering misconduct cases involving police.

California Assembly member Rob Bonta (D-Alameda), who recently told the San Francisco Chronicle he is considering challenging O’Malley in the 2022 election, said he plans to introduce legislation next year that would require prosecutors to recuse themselves in misconduct cases involving law enforcement agencies whose unions had donated to their campaigns — legislation that’s sure to be contentious at the state Capitol.

Cooley said he believes candidates such as Gascón — a longtime former LAPD officer and former police chief in Mesa, Ariz., and San Francisco — have helped foster an anti-law enforcement sentiment that will harm police and increase crime in L.A. and other cities

“Law enforcement is going to change their ways. They are not going to be as proactive,” he said. “You’re going to see more drive and wave policing.”

Although fears of crime surges have been commonly used to criticize progressive challengers, that rhetoric hasn’t entirely lined up with reality in cities where such candidates won office.

San Francisco did see a 37% surge in its property crime rate under Gascón, though violent crime remained relatively flat and the city saw a historic low in killings during his last year in office. In St. Louis, violent crime remained unchanged and property crime has fallen by more than 7% under reformist prosecutor Kim Gardner, records show. Philadelphia has seen a surge in homicides under Krasner, but overall crime rates have remained relatively static.

Eugene O’Donnell, a former New York City police officer and prosecutor who now teaches at the John Jay School of Criminal Justice, also worried that the influx of money into races like the one in L.A. County, where Lacey and Gascón have courted millions from police unions and progressive boosters, has led such contests to be framed around broad ideological issues rather than those affecting local public safety.

“My concern about this is it’s not getting us to a place where we’re having a serious conversation about public safety at all … or even justice. They’re just proxy wars for really wealthy people.”

Others say the emergence of Gascón and other reform candidates is the result of aggressive organizing by voters and activists who want to see a criminal justice system guided by rehabilitation, rather than punishment.

“Often times the prosecutor is the face of reform, but really they are the response to the movement that has been fighting this fight for a long time,” said Jonathan Rapping, president and founder of the public defender organization Gideon’s Promise and an Atlanta-based law professor. “They are the result of activists and organizers and public defenders who have really been, I think, creating an environment that welcomes this new kind of prosecutor.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.