- Share via

CLOVIS — In the haze outside his family trailer, he stubs out a cigarette and stares off across the hospital parking lot in Clovis where he has hitched up for now, pondering his future in California.

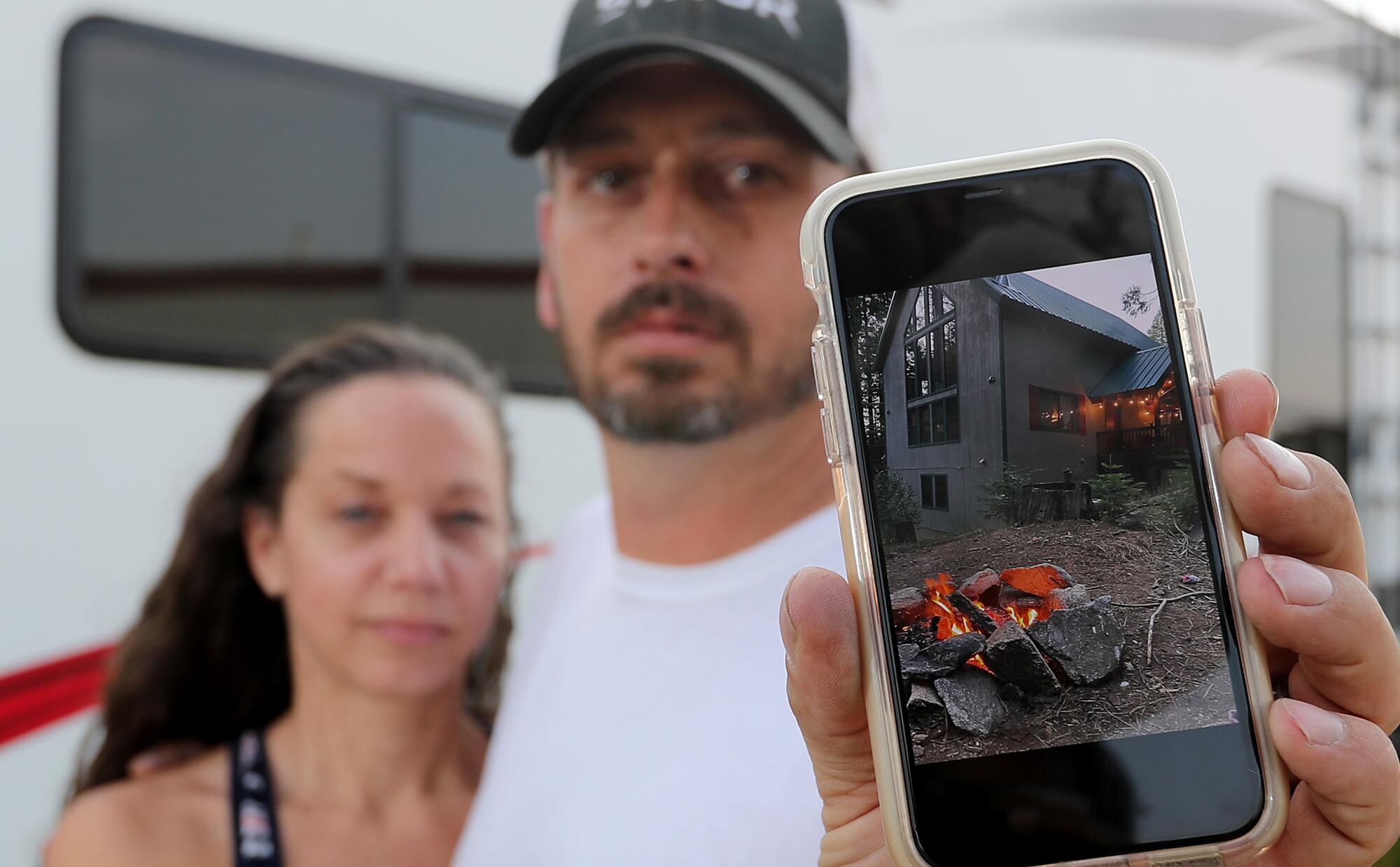

Just weeks before, Mark Van Aacken, 40, was living his idyll. He and his wife owned a home on a 5-acre parcel of white firs, dogwoods, ponderosas, sugar pines and incense cedars. Their 7-year-old twin girls roamed free, riding bikes, exploring the woods. On weekends, they packed their heavily modified Grand Cherokee — one-ton axles, 40-inch tires — and low-geared it up boulder-strewn Jeep trails to camp next to blue alpine lakes. That high granite country was where he found those moments of natural bliss at the heart of California’s promise.

But now his home in Shaver Lake is gone, taken by the flip side of that promise: disaster. The Creek fire torched not only the house but every single tree on his property.

“We moved up there for the forest. And now it’s not there.”

He is feeling lost and in limbo, like so many others besieged by the worst fire season on record.

With climate models predicting a hotter, drier California, many wonder what the state will look like in the decades to come. What places might be too risky to live in? What great icons of nature will be left in a land so long defined by its extremes?

The California landscape has excited such an enduring sense of wonder that it is as much a concept as a place, having drawn its own canon of literature, amassed by the likes of Mark Twain, John Muir, Jack London, Mary Austin, John Steinbeck, Wallace Stegner, Joan Didion, John McPhee, Barry Lopez and so many others.

The land is so inextricably tied to the culture and self-image of the state that relentless years of burning, coupled with sea rise and a diminishing water supply, can only demystify the dream that was millions of years in the making.

No one can answer what, exactly, will come. But with a record-shattering 4 million acres burned in three months, the smoked-out people in the ever-expanding ring of fire are forced to envision their own fates.

This month a Times reporter and photographer traveled a loop of much of the state’s more populated timber country — up the Western Sierra, across the Central Valley to Lake, Mendocino and Sonoma counties — to see how the explosion of fires over the last five years has taken a toll on communities and ecosystems, to see where there is resilience and where there is retreat.

This longer narrative of life in the fire zone is often lost during the blazes themselves, drowned out by headlines of catastrophic loss and harrowing escape; the outside world predicts California’s doom during every bad fire season, and questions why people even live here.

“I’ve long been struck by how many Californians are acutely aware that their lives are unfolding against what’s arguably the most diverse, most stunning weave of nature to be found anywhere in North America,” said Gary Ferguson, a naturalist and author who frequently writes about the ecology of the American West. “I think this actually has much to do with the state’s sense of confidence, of possibility.

“Hearing about giant sequoias dying from a megafire, or for that matter the more than 130 million other trees that have died from drought and related beetle kill in the past decade, brings to many a sense of their larger community being harmed.”

The reality is as devastating as it is nuanced: Wildfires don’t simply scorch to dirt huge swaths of the state’s surface every year; they burn through forests in a mosaic. The vast majority of people in a fire zone don’t lose their homes. And burned-out areas, depending on the intensity of the blaze, usually start recovering the following spring. But few doubt the fires will become bigger and more frequent and a large number of Californians will have to expect repeated disruptions to their lives — or worse.

“It’s spooky up here because I have no neighbors now,” he said. “It’s like the ‘Twilight Zone’ of the end of the world.”

— Charles Mefford, Berry Creek resident

As for the plant communities, ecologists, fire scientists, naturalists and climatologists don’t envision some permanent hellscape. They predict some forests will transform to chaparral and oak woodland, as fires continue to increase in magnitude and heat, particularly in the mid-elevations of the Sierra Nevada, the Cascades and the Klamath Mountains. Thicker forests will move to higher altitudes where they can.

Nor do the experts say this terrible year necessarily presages fire seasons to come. A calamitous set of circumstances came together this season. A rare August dry lightning siege over much of Central and Northern California ignited some 650 blazes, many in areas where trees were abnormally dry or dead from drought and bark beetle infestation. Then came a record-breaking heat wave over Labor Day weekend, followed by heavy downslope winds just four days later. While climate change probably affected many of these factors, no one expected all of them to converge with such disastrous timing.

“This is an anomalous event,” said Jon E. Keely, a fire ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. “It’s what I would describe as a perfect storm.”

And yet, the notion that there could be more fire seasons like this — with the entire state hacking in smoke — is forcing people to make wrenching decisions like never before.

The option to uproot is not easy. People have deep bonds to these increasingly vulnerable areas — family networks, businesses, farms, childhood memories, sentimental attachments to the streams, lakes and mountaintops. In the more remote corners, many are living on limited income, in trailers and outbuildings, and could not afford the cities even if they wanted to go there.

Berry Creek has been many things in its long history — a stagecoach stop, a lumber town, a vacation spot, a gold mining camp.

“This is the type of place homeless people can come live in a trailer and not be bothered,” says Tyler Burrett, 27, of his mountain community, Berry Creek.

The Bear fire destroyed more than 1,000 structures here on Sept. 9 and killed 14 people. Burrett was living with his wife in her parents’ barn when all four escaped safely down the mountain. Burrett and his wife returned a week later with a trailer and plan to stay and help rebuild the community.

Her parents drove south to a well-paved, manicured suburb in Temecula and say they are done with rural fire country.

While wealthier towns have the means to build fire-protected homes, Burrett envisions a more mobile Berry Creek in the future, with RVs and trailers that can be driven out at a moment’s notice.

Ferguson said that although California is the leader in trying to create fire-safe communities with better building and zoning codes, there are places where fire fatigue could push humans out. He wonders “whether or not there are some places in California, and in the Mountain West in general, that really should not be buildable, because there’s too much risk for fire.”

The anguish comes because there is no moment of absolute clarity.

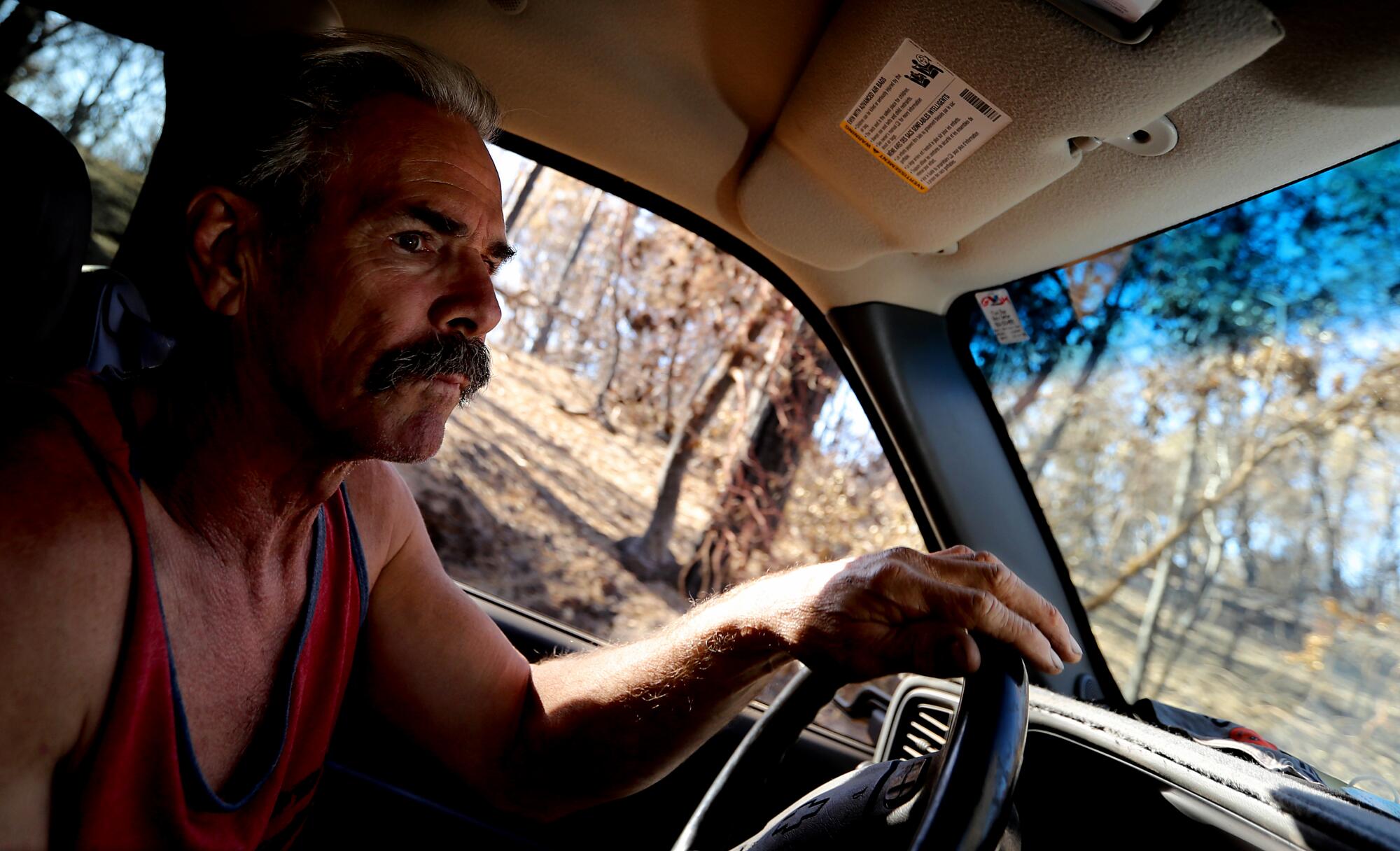

Charles Mefford, 64, bought an old A-frame cabin in Berry Creek for $55,000 in 2007 and fell in love with the place. He canoed on Buck Lake and reveled in making a mental inventory every day of what wildlife he spotted: bear, deer and mountain lions, timber rattlers and whip snakes, blue-bellied lizards and green skinks. At dusk, he’d step out to watch the bats feast on the mosquitos and gnats.

Two years ago, when the Camp fire destroyed the town of Paradise just over the ridge, he was spooked. His brother called him from Tennessee and told him, “Get out of there or you’re going to die there.” But he had no plans to leave.

Then in September, the Bear fire roared through Berry Creek. Mefford’s house was the only one on his road still standing. He lost a shed and a 17-foot trailer. “It’s spooky up here because I have no neighbors now,” he said. “It’s like the ‘Twilight Zone’ of the end of the world.”

Yet pockets of trees remain singed or unscathed and many torched ones have already sprouted green shoots from their base, even before the rains. While Mefford wonders what will come back in spring, he’s already called a real estate agent to talk about listing his property. He thinks he might move to Tennessee to be around his brother and grandchildren.

Just talking about it chokes him up.

“My heart is in California,” he said. “Every time I think about leaving, I get emotional.”

***

John Abatzoglou, a climate scientist at UC Merced, said 2020 was an “unlucky year made unluckier by long-term climate change” and a century of fire suppression that allowed vegetation to build up.

“The most unlucky part of it was the lightning siege that set a ring of fire around the Bay Area,” he said.

But even if ignitions remain stable, the models predict warmer years, drier fuels and longer fire seasons, with conditions worsening most dramatically in densely forested northern parts of the state.

“The locus of fire activity has certainly shifted north to the wetter parts of the state where there is more fuel,” Abatzoglou said.

He says the Mediterranean biome of Southern California is always dry enough to burn in summer and fall, so the warming alone might not magnify the risk as much it will in the heavy fuels to the north. “The megafires in Southern California are normally driven by Santa Ana wind events, so that puts the onus more on the weather than the climate.”

But every factor is integral. Combined with these downslope winds, a later start to the rainy season — even two or three weeks — could lead to more megafires. While Californians normally associate the big downslope winds like the Santa Anas with mid-fall, they are most prevalent — and stronger — in December and January.

“If you miss your fall rainstorm that would have shut down the fire season, you extend that much further into that part of the year that you’re more likely to get a big wind event,” said LeRoy Westerling, a climate scientist, also at UC Merced.

Westerling was a coordinating lead author of California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment in 2018. His models on fire compared what burned in 1961-1990 to projections for 2035-2064 and 2070-2099, based on a multitude of scenarios.

His researchers generated millions of maps for every month of every 36 square-kilometer grid in the state.

In almost every scenario, the amount of burned area in parts of the Western Sierra, the Cascades and the Klamath Mountains more than tripled by 2070, with the mid-elevation, 4,000-to-8,000-foot mixed conifer zone suffering the most.

“That area between Mariposa and El Portal is also where the biggest absolute increase in fires is projected to happen,” he said. This is the area abutting the western edge of Yosemite National Park.

There were other hot spots, such as one in the Santa Cruz Mountains on the border of Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties. Westerling’s team presented the findings in San Mateo to local officials and firefighters so they could use them for planning.

The locals were dubious, he said, because they had “this marine layer that comes in and wets things down.”

This summer, in the same area Westerling was pointing to, the massive CZU Lightning Complex fire burned nearly 90,000 acres.

“People were skeptical that we would see these by 2050 and we already have an example of one in 2020,” he said. “We drew that map in 2018 and saw it happen on the ground in 2020.”

Part of that equation is that the marine layer is diminishing. A UC Berkeley study found a 33% reduction in the coast’s famous fog that, as Steinbeck wrote, “rolled in like herds of sheep” and fed the forest through the rain-less summer. That’s particularly troublesome for the coastal redwood, the tallest tree in the world and a driver of a critical tourism economy.

Winemakers who rely on the fog can adapt by changing their varietals, replacing pinot noir and cabernet with grapes such as tempranillo or shiraz. Two-thousand-year-old trees can’t evolve so fast.

How many more scorched summers can the king grape of Napa Valley survive?

The redwoods’ towering limbs scoop the cool vapor as it drifts inland, drinking it in through the stomata in their needles while also giving it a surface to condense and drip to the ground, feeding the roots just like rain.

In the southern part of the redwoods’ range, the Santa Cruz Mountains and Big Sur, the Cal researchers are already finding drought stress.

“We saw clear signs of slowed growth, thinning tree crowns (loss of needles) and levels of water stress in redwood trees we’d never measured before in the southern redwood stands south of Big Sur,” said UC Berkeley professor Todd Dawson.

“This past August, some of these southern redwood stands were lost in the lightning fires that swept through Central California. And experienced firefighters said they had never seen coast redwood burn in the way it did in the Big Sur area and in the Big Basin State Park where the destruction was terrible.”

He said continued “warming and drying conditions along the coast” will lead to more wildfires and more loss of forested landscapes.

In the Sierra, scientists are finding similar stress in California’s inland redwood, the giant sequoia — the world’s most massive tree.

The behemoths are built to survive dozens of fires in their lifetime. Historically, fires helped by clearing ground cover and allowed their seedlings space to grow. But fire suppression in the Western Sierra over more than a century has left such a buildup of fuels that blazes such the Rim fire in 2013 and last month’s Creek fire burned high into the canopy in many places with much more intense heat. Researchers fear repeated fires like these could have a devastating impact on the estimated 65 groves of giant sequoias. So far, firefighters have managed to protect them.

What has forest managers concerned on a wider scale is that these crown fires burn with such ferocity that nothing is left to re-seed that part of the forest, allowing brushland and invasive species to take over.

In the lower elevations, heat and drought alone might lead to similar “vegetation conversion.”

“As we’re warming things up, we realize these trees that exist on the landscape may have actually been established 100 or 200 years ago,” Abatzoglou said. “So they established in a much cooler climate. They had more water to work with. Will they establish today, is a different question. So what we may see in some of these areas is forest being replaced by shrub lands or grasslands. The landscape will recover, but it will change.”

Rob Brown, 60, has watched the patchwork of forest, woodland brush and orchards in his native Lake County evolve all his life. The Valley fire burned through 76,000 acres of conifer forest in 2015.

“Oaks and manzanita are coming back pretty strong there right now,” he said.

Brown is a rancher, bail bondsman and 20-year county supervisor whose grandfather first came here in the 1930s to raise sheep.

From a construction job he’s overseeing in Kelseyville, he points to a hill that was once forested and is now thick chaparral. “That’s chamise right there. You couldn’t walk through it.” He sees the change as inevitable, and a folly for humans to try to stop.

He thinks residents need to be more vigilant in clearing brush and fireproofing their homes, and not count on government to protect them.

He talks about the hamlet of Cobb, where hundreds of homes burned during the Valley fire.

“If you go up on Cobb right now, you’ll see that much” — Brown holds his fingers four inches apart — “in pine needles on top of the roofs.”

“They’re just asking for trouble,” he said. “I’ve got 500 acres. I’m on the bulldozer all the time, clearing brush. It’s expensive. But that’s part of being a landowner.”

Forecast: warm, dry and prone to fires

Here is how some scientists envision California’s future

He is sick of the fires. The August Complex blaze burning to the north — the largest fire in California history — has smothered his county in smoke for two months. He plans to head down to Santa Rosa the next day to hook up to a nebulizer to clean his lungs out.

He says he knows people who are leaving, mostly retirees who are sick of evacuating and want to be near grandchildren or closer to a hospital. He plans to stay, for the most part, because the truth is, “It’s beautiful here most of the year.”

He is building a home with concrete siding, windows sheltered by a composite wrap-around porch and no vents to let embers in.

“I’m getting married and I told her, hey, next year, the minute the first fire starts we’re going to lock everything up and head out of town. There’s no point in staying. Go to Idaho for a while. When the smoke clears, let me know and we’ll come back.”

With young kids and a job, Van Aacken can’t be that flexible. He thinks about rebuilding. But he wonders if his insurance will be cost-prohibitive and whether what drew him to the area will ever come back.

“People want to have this big go-forward attitude on rebuilding everything up there, but there’s a lot of people that are very unsure,” he said.

He floats the idea of relocating to places such as Montana or Idaho, but he’s never spent time there, and fires are worsening throughout the Mountain West as they are in California.

On Oct. 17, Van Aacken towed the trailer back up to Shaver Lake and set it up on his father’s property, which survived the fire. His plan was to stay through winter and see how he and his wife felt looking at all that burnt terrain.

“We might be up there . . . and staring at it for quite a while, we might just say forget it,” he said.

He’ll go look for California’s promise somewhere else.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.