Coronavirus takes wrenching toll on Orange County Latinos who have no choice but to work

- Share via

As the coronavirus swept through Orange County this summer, Huntington Beach became a national flashpoint because many residents and visitors refused to wear masks, and its streets saw several big protests opposing California’s stay-at-home order.

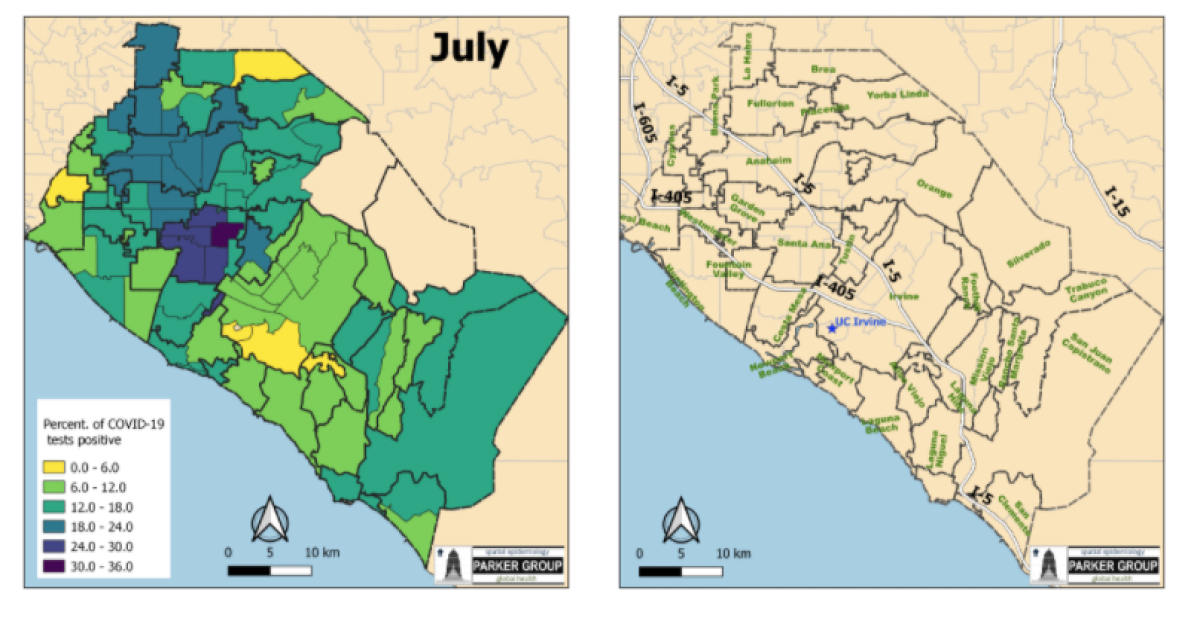

But data show COVID-19 has delivered its most brutal blow not along Orange County’s upscale coast but in the densely populated, heavily Latino communities.

Santa Ana and Anaheim — the two largest cities in the county — have had positive coronavirus test rates more than double that of the overall rate in Orange County.

While Orange County recently reported a seven-day positive coronavirus test rate of 3.1%, the rate in Santa Ana was more than double that, at 8.5%. Anaheim had a positive test rate of 4.8%, a figure that’s more than 50% higher than the countywide rate.

The positive test rates for Orange County’s most populous cities were much worse about a month ago. At a time when the countywide positive test rate was between 5% and 6%, the rates for Santa Ana and Anaheim were roughly between 15% and 19%, Dr. Clayton Chau, the Orange County Health Care Agency director, said at the time.

Orange County overall is 34% Latino, though its two most populous cities are far more heavily Latino. Anaheim is 56% Latino, and Santa Ana 77%.

The results are consistent with statistics across California and the nation showing that Latinos have been infected, hospitalized and killed by the coronavirus at disproportionate rates compared with their share of the population.

“If you look at the numbers in Santa Ana and Anaheim, these are communities that most likely work in the service sector in other parts of the county — Irvine, Huntington Beach…. They are essential workers. They work in restaurants and kitchens and as janitors,” said Carlos Perea, an immigrant rights activist in Santa Ana. “They are exposed to COVID, and a lot of them don’t know about their workplace rights during COVID and they have to make ends.”

In Orange County, Latinos account for 47% of coronavirus cases and 45% of COVID-19 deaths, despite comprising 35% of the population.

Across California, Latinos account for 61% of the state’s cases and 49% of COVID-19 deaths, despite comprising 39% of the population. Black Californians account for 8% of the state’s COVID-19 deaths but 6% of the population.

Latinos and Black Californians make up a disproportionate share of California’s low-wage workforce, who often work in essential jobs critical to keeping the state’s economy functioning. In nearby Los Angeles County, some of the worst outbreaks hit workplaces in industries that are staffed mostly by Latino workers, such as in garment manufacturing and food processing facilities — companies that have come under investigation for violating county health requirements.

Compared with the rest of Orange County, Anaheim and Santa Ana are also home to lower-income residents, many of whom live in crowded homes.

Residents there are “vulnerable from the economic standpoint, vulnerable from the housing standpoint,” Chau said recently. Many residents in Anaheim and Santa Ana “do not have the luxury to telecommute [and] stay home; they have to risk their lives to earn a living to put food on the table and a roof over their family’s head.”

UC Irvine physicians began noticing that many COVID-19 patients were coming in from Anaheim and Santa Ana, said Dr. Shruti Gohil, associate medical director of epidemiology and infection prevention at UC Irvine and a professor of infectious diseases.

“Those were the top two highest since the beginning of our upswing,” Gohil said. As the summer wore on, neighboring areas also saw a rise in COVID-19 infection rates. “It rings out from there. In other words, the [places] around them become infected as well.”

This is why it is so important to continue focusing on reducing disease levels in the hardest-hit areas, experts say, even as a county overall might be seeing more improvement. “It starts in any one place and it is — as expected — propagating to other places,” Gohil said.

State officials say they intend to establish a “health equity metric” soon that would push counties to reduce the disproportionate effects of the pandemic on the hardest-hit communities.

An analysis by UC Irvine showed that positive test rates were higher in July in other nearby cities such as Buena Park, Garden Grove, Fullerton, La Habra and Placentia, all of which have significant Latino populations.

Santa Ana has a cumulative coronavirus case rate of more than 3,000 cases per 100,000 residents; Anaheim, more than 2,500 cases per 100,000 residents. By contrast, Irvine, a relatively wealthy suburb and Orange County’s third-most populous city, cumulatively has nearly 600 cases per 100,000 residents.

Predominately Latino neighborhoods of other more upscale Orange County cities are also being hit hard.

The 92647 ZIP Code, which encompasses the predominantly Latino Oak View neighborhood of Huntington Beach, accounts for 880 of the 2,387 cumulative coronavirus cases in the city — nearly 37% as of Saturday.

A good portion of the Latinos who live in the Oak View community work in downtown Huntington Beach — a worldwide tourist destination that remains open to the public. The city has also become the epicenter of mask resistance and COVID-19 doubters in California.

“The people in our community are at great risk,” said Oscar Rodriguez, a 26-year-old who grew up in the Oak View neighborhood and is co-founder of the grass-roots group Oak View ComUNIDAD, which seeks to serve marginalized neighborhoods throughout the city. “Many from our community are the folks who are providing these services and provide the labor at the restaurants and hotels in the downtown area. They are the economic power engine behind this industry.”

In the U.S., Latinos have been disproportionate casualties of the virus. They are about 39% of the population in California, but Latinos make up 60% of positive cases and 48% of deaths.

Rodriguez, who will be on the ballot for City Council in November, said many in Oak View who have been infected with the coronavirus are afraid to speak out.

“They are not willing to talk about it because it’s all so stigmatized,” Rodriguez said.

Part of the solution requires intense intervention in hard-hit communities, experts say. Low-income workers may be reluctant to speak up about health violations, and efforts should be made to encourage anonymous tips to county inspectors, officials say.

Experts add that employees need to be assured that they will see wage replacement if they become infected or need to take care of a loved one who is sick, and be guaranteed they won’t be fired if they take time off for sick leave. Alameda County launched a program to offer stipends of $1,250 for those who test positive, are not receiving unemployment or sick leave, and are referred by designated clinics in high-risk neighborhoods.

Orange County has launched a Latino Health Equity Initiative to team up with nonprofits and agencies to provide education, resources and testing to the communities that need it most.

Experts say it’s essential that workplaces implement new safety protocols required to keep workers safe amid the pandemic, which include notifying the county about outbreaks.

In neighboring Los Angeles County, Óscar Ramírez, a lawyer representing the family of 67-year-old worker José Roberto Álvarez — the head of maintenance at Mission Foods Corp. in Commerce — alleged Álvarez’s employer failed to “reveal a massive outbreak to all the workers” as was its obligation.

L.A. County officials temporarily shut down the facility after saying the company failed to notify authorities of the outbreak.

Alisha Álvarez said her father, who had diabetes and high blood pressure, “was afraid of saying that he couldn’t come to work, because he believed that he would be fired.” Her father tested positive for the coronavirus June 28, was taken to the hospital July 4 after having trouble breathing, and died July 20.

A statement on behalf of Mission Foods, a leading distributor of tortillas, chips and salsas, said the company had provided the required information about cases among its workforce that it was aware of. The company said it has encouraged and allowed high-risk individuals who may be concerned about contracting the disease to take leaves of absence.

Soudi Jiménez writes for Los Angeles Times en Español. Times staff writers Jaclyn Cosgrove and Maya Lau contributed to this report, as did Sara Cardine of Times Community News.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.