Newsom orders 2035 phaseout of gas-powered vehicles, calls for fracking ban

California will halt sales of new gasoline-powered passenger cars and trucks by 2035, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced Wednesday, a move he says will cut greenhouse gas emissions by 35% in the nation’s most populous state.

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Emphasizing that California must stay at the forefront of the fight against climate change, Gov. Gavin Newsom on Wednesday issued an executive order to require all new cars sold to be zero-emission vehicles by 2035 and threw his support behind a ban on the controversial use of hydraulic fracturing by oil companies.

Under Newsom’s order, the California Air Resources Board would implement the phaseout of new gas-powered cars and light trucks and also require medium and heavy-duty trucks to be zero-emission by 2045 where possible. California would be the first state in the nation to mandate 100% zero-emission vehicles, though 15 countries already have committed to phasing out gas-powered cars.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Newsom did not take executive action to ban the controversial oil extraction method known as fracking but called on the state Legislature to do so, setting up what could be a contentious political fight when lawmakers reconvene in Sacramento next year.

Taken together, the two climate change efforts would accelerate the state’s already aggressive efforts to curtail carbon emissions and petroleum hazards and promise to exacerbate tensions with a Trump administration intent on bridling California’s liberal environmental agenda.

“In the next 15 years we will eliminate in the state of California the sales of internal combustion engines,” Newsom said at a news conference in Sacramento before signing the order. “If you want to reduce asthma, if you want to mitigate the rise of sea level, if you want to mitigate the loss of ice sheets around the globe, then this is a policy for other states to follow.”

Newsom’s executive order calls ending the sale of new gasoline-powered cars by 2035 a “goal,” but it also orders the Air Resources Board to immediately begin drafting regulations to achieve it by that year.

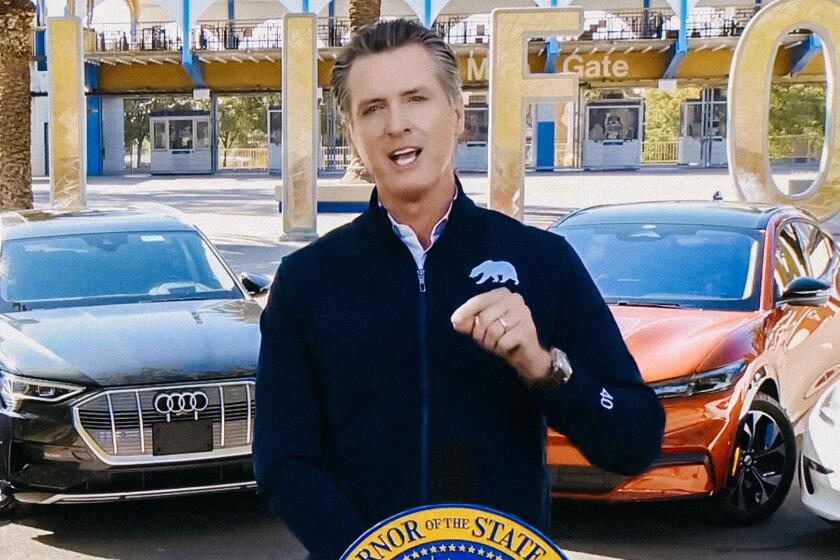

California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s executive order to ban new combustion cars by 2035 will reshape the California car market.

The governor acknowledged that not everyone would embrace the 100% zero-emissions mandate but emphasized that nothing in his order would prevent Californians from owning gas-powered cars or buying or selling them used.

“We’re not taking anything away,” Newsom said. “We’re providing an abundance of new choices and new technology, being agnostic about how we get to zero emissions, but being committed to getting to zero emissions by 2035.”

Newsom said that California’s action will help spur greater innovation for zero-emission vehicles and, by creating a huge market, will drive down the cost of those cars and trucks. More than 1.63 million new cars and trucks are expected to be sold in the state in 2020, according to the California New Car Dealers Assn.

He noted that California is home to 34 manufacturers of electric vehicles and that just under 50% of all the electric vehicle purchases in the country are in this state. Phasing out gas-powered cars will not only reduce the hazards posed by carbon emissions but will also serve as a catalyst to bring more green jobs to California, he said.

Climate scientists and advocates say the world must stop production of gas- and diesel-powered vehicles by 2030 in order to keep global warming to tolerable levels. California and other governments across the world are seeking to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045, and it will take years for vehicles to turn over and be replaced by zero-emission models.

Beau Boeckmann, president of Galpin Motors dealerships in Los Angeles, said the 2035 mandate “sounds a little scary to some at first blush,” but that everything evolves in this changing world, and everyone needs to prepare for it. The auto industry eventually will benefit by doing to right thing, he said.

“Pollution is a terrible thing. I grew up in the San Fernando Valley in the 1970s, and you couldn’t see across the valley with that brown haze,” Boeckmann said. “L.A. was known for smog like London was known for fog.”

California’s governor called record-breaking heat and wildfires a “climate damn emergency.” Actions speak louder than words.

Alliance for Automotive Innovation President and Chief Executive John Bozzellas said the electric car market is crucial to auto manufacturers, but “neither mandates nor bans build successful markets.”

State Senate Republican leader Shannon Grove of Bakersfield, which is in the heart of California oil country, criticized Newsom’s order as “extremist,” saying the governor’s time would be better used protecting Californians from wildfires rather than banning cars that most state residents rely on to provide for their families.

“The fact is that Californians cannot survive without oil and gas or petroleum byproducts,” Grove said. “These products are not just the gas in our cars, they are the asphalt on our roads, the plastic holding together electric vehicles, medical equipment vulnerable patients rely on, footballs our children play with, telephones, toothpaste, trash bags, and so much more.”

Cathy Reheis-Boyd, president of the Western States Petroleum Assn., noted that Newsom had lined up expensive zero-emission cars as a backdrop to his news conference.

“It’s interesting that the governor was standing in front of nearly $200,000 worth of electric vehicles as he told Californians that their reliable and affordable cars and trucks would soon be not welcome in our state,” she said. “Big and bold ideas only make sense if affordable for us all and backed by science, data and needed infrastructure.”

In his announcement Monday, Newsom stopped short of mandating health and safety buffer zones around oil and gas wells and refineries. His executive order directed the state Department of Conservation to consider such zones as it drafts regulations to protect “communities and workers from the impacts of oil extraction activities,” but the agency already is doing so.

Newsom has resisted calls by environmental and public health advocates to implement those zones immediately.

Newsom sharply criticized the Trump administration this month for ignoring the reality of climate change, saying that California’s deadly wildfires, some of the largest in state history, were grim reminders of what lies ahead for the nation if political leaders in Washington don’t take action.

“This is a climate damn emergency,” Newsom said during a tour of the charred landscape around the Northern California town of Oroville. “This is real, and it’s happening.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom visited an area burned by wildfires in Oroville, Calif., on Friday and called the Trump administration to task for its record on climate change.

While meeting with Newsom in Sacramento last week, Trump expressed skepticism about the scientific evidence of climate change, saying: “It’ll start getting cooler. You just watch.”

The state has sued the Trump administration over efforts by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to rescind a special federal waiver that permits California to set its own strict pollution controls to improve air quality, the foundation of the state’s aggressive efforts to combat climate change.

Environmentalists who had urged Newsom to accelerate California’s climate action praised his order to transition to zero-emission vehicles.

Newsom’s order “will not only address the single largest source of climate and air pollution in California but is a major step toward boosting his state’s economic competitiveness and helping Californians who are suffering extraordinary harms from air pollution,” said Fred Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund.

At the same time, many other environmental groups faulted him for not doing more to restrict fossil fuel production and to protect the health of people living nearby.

“If your climate leadership does not include relief for hundreds of thousands of Californians — the majority people of color — living with oil drilling in their neighborhood, then you are not serious about climate justice,” said Martha Arguëllo, executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility-Los Angeles.

In November, Newsom imposed a temporary moratorium on new hydraulic fracking permits, saying he wanted them to undergo independent scientific review. Since April, however, his administration has issued close to 50 new permits to Chevron and Aera Energy, frustrating environmentalists.

Legislation to put mandated minimum space between oil wells and homes, as well as schools and playgrounds, failed passage in a California Senate committee.

“Newsom is really good at making announcements that sound big, but they actually aren’t. We can’t let the fact that he’s acting on cars eclipse the fact that he’s still protecting the oil industry,” said Kassie Siegel, director of the Climate Law Institute at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Siegel’s organization this week threatened to sue Newsom unless he halted all new permits for gas and oil wells in the state, saying the governor has failed to protect the health of vulnerable Californians from pollutants released by the state’s petroleum industry.

Since taking office, Newsom has faced pressure from politically influential environmental groups to ban new oil and gas drilling and completely phase out fossil fuel extraction in California, one of the nation’s top petroleum-producing states.

But the Democratic governor has pushed back, promising to take a more measured approach that addressed the effects on oil workers and California cities and counties that are economically dependent on the petroleum industry.

California has 1,175 active offshore wells and 60,643 active onshore wells. In 2019, the state produced just under 159 million barrels of oil, CalGEM records show. The state’s annual crude oil production has been consistently declining since 1985.

California oil industry representatives have argued that phasing out oil production in the state, which has some of the strictest environmental regulations in the world, would force more oil to be imported by train and tanker ship from countries that do not have the same environmental safeguards. According to the Western States Petroleum Assn., there are more than 26 million vehicles with internal-combustion engines in California.

Newsom’s order directs the state Air Resources Board to develop and propose regulations that require increasing volumes of new zero-emission passenger vehicles sold, “towards the target of 100% of in-state sales by 2035.”

The order also tasks air quality officials with crafting similar rules to ensure all trucks moving freight through the state’s seaports are zero-emission by 2035. That mirrors targets set three years ago by the mayors of Los Angeles and Long Beach aimed at slashing emissions from the San Pedro Bay port complex, which remains Southern California’s biggest single source of smog-forming pollution.

Across California, cars, trucks and other vehicles are the largest emitters of greenhouse gases, accounting for about 40% of the statewide total, and their emissions have been stubbornly creeping upward in recent years. Driving down transportation pollution remains the state’s biggest challenge in achieving its goal of slashing planet-warming emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030.

Joe Biden vows he won’t ban fracking. But in Pennsylvania, many voters are skeptical, and Trump is exploiting their anxieties in a key battleground.

Under current regulations, California’s Air Resources Board requires automakers to sell electric, fuel cell and other zero-emission vehicles in increasing percentages through 2025. Electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles accounted for 7.6% of new car registrations in California in 2019.

In 2018, under then-Gov. Jerry Brown, the state set a goal to put 5 million zero-emission cars on the road by 2025. There were 670,000 zero-emission vehicles sold in California through the end of 2019, according to auto industry sales data.

In June, the Air Resources Board adopted the nation’s first sales mandate requiring heavy-duty truck manufacturers to sell increasing percentages of electric or fuel cell models until all new trucks sold in California are zero-emission by 2045.

But efforts to completely phase out gas-powered cars have not gained traction. Three years ago, Brown directed the state’s chief air quality regulator, Mary Nichols, to look into stepping up the state’s timetable. Prior to Wednesday, her agency had only floated the idea of banning gas-powered vehicles in congested areas of the state. And legislation lawmakers introduced in 2018 that would have banned the sale of new, gas-powered vehicles by 2040 didn’t move forward.

State Assemblyman Phil Ting (D-San Francisco), who wrote that legislation, said “the fastest way to make the biggest dent in slowing the effects of global warming is to embrace cleaner cars” and applauded Newsom “for putting us on a path that’s not only crucial for our planet, but also helpful in spurring green jobs as we recover from COVID-19.”

Nichols said Wednesday that the Air Resources Board is ready to move forward with the governor’s zero-emissions order and that its scientists, engineers and lawyers “are working to try to figure out how we can deal with the persistence of smog that makes people sick and also at the same time try to get ahead of this escalating climate problem.”

She expressed confidence that the Trump administration’s efforts to remove California’s authority to set stricter emissions standards, which the state is currently fighting in court, would not pose an obstacle to the governor’s new mandate.

“We believe the Clean Air Act gives us the authority to set exactly the kinds of standards that we have set since the late ’60s,” Nichols said, “and therefore we look forward to being able to do that in the future.”

Times staff writer Russ Mitchell contributed to this report.

Trump and Biden hold radically different views on environmental policy and climate change. Here’s what voters can expect from the next president.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.