- Share via

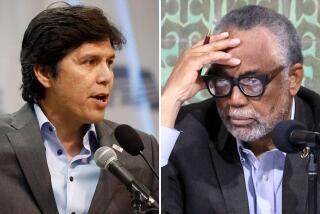

When a real estate developer proposed a $1.2-billion skyscraper complex just south of downtown, Los Angeles City Councilman Curren Price stepped forward to champion the project, despite warnings that it would accelerate gentrification in South Los Angeles.

Price urged his colleagues to approve the development in 2016, saying it would create hundreds of jobs. He also ensured that developer Ara Tavitian received permission to install three huge digital billboards on a 12-story building already located on the site, over strong objections from city planning commissioners.

Three months later, three of Tavitian’s real estate companies poured $75,000 into a political action committee working to reelect Price.

Construction still hasn’t started on the skyscraper complex, which would go up next to the existing building and add 1,444 apartments and condominiums, a 208-room hotel, a supermarket and other attractions. But the property owners have already installed the digital billboards, sparking complaints from those who live and work nearby.

Jorge Nuño, who ran unsuccessfully against Price in 2017, said he and his neighbors were stunned by the size and the brightness of the signs, which wrap around three sides of the building, each measuring about 55 feet by 245 feet.

The billboards, which can be seen clearly from the 10 Freeway, are a dangerous distraction for drivers and never would have been allowed in wealthier parts of town, he said.

“The only ones that are really benefiting from this is the developers — and Curren Price,” said Nuño, who owns a printing and marketing shop a mile south of the site.

The skyscraper project, which has been marketed as Broadway Square Los Angeles, but is more widely known as the Reef, also emerged recently as one element in the ongoing corruption investigation into City Hall.

- Share via

Three digital billboards have gone up on the 12-story building known as The Reef, prompting complaints from residents and business owners. The images can be seen easily from the 10 Freeway.

Although federal prosecutors do not mention the project by name, key details in a criminal complaint identify the Reef’s developer as one of several allegedly squeezed by Councilman Jose Huizar for five-figure donations right before a crucial vote.

Price, whose district includes the Reef, was named in a 2018 search warrant filed by the FBI as part of the probe. However, the 113-page Huizar indictment makes no mention of Price or his handling of the Reef.

Prosecutors have not publicly accused Tavitian or his company, PHR LA Mart, of any wrongdoing. Price has not been arrested or publicly charged.

Even if the Reef ends up as a bit player in the corruption scandal, the project offers an example of a familiar scenario at City Hall: a council member takes crucial steps to help a developer, who in turn spends tens of thousands of dollars on that council member’s behalf. Such spending is generally legal, if it is not in exchange for an official action, but can erode public trust in city decisions.

Price declined to answer questions from The Times about the project, the political spending by the Reef’s developer and the ongoing federal investigation.

“Councilmember Price is committed to fully cooperating as requested by the authorities in these important matters,” said spokeswoman Angelina Valencia in an email. “Out of respect for those ongoing matters, he has been advised to not answer these questions at this time.”

Tavitian did not respond to messages left at his office. Lawyers and a lobbyist for PHR LA Mart did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Digital billboards are not new to downtown Los Angeles, going up on hotels, apartment buildings and the entertainment zone known as L.A. Live. But they’ve been largely confined to the city’s Sports and Entertainment District, which is centered around Staples Center and the city’s convention complex.

The Reef property, which sits on the border between downtown and South Los Angeles, is well outside that district. And although it is mostly surrounded by parking lots and government buildings, its new digital signs shine into the windows of nearby homes and offices.

José Tlatenchí, who lives just east of the Reef site, said he and his family have had to shut the curtains at night, or keep the lights on indoors, to cut down the glare. His teenage daughter, who is autistic, complains regularly about the signs, which are allowed to stay on until midnight on Fridays and Saturdays.

“Sometimes I can’t sleep,” the 60-year-old said in Spanish.

With its mix of condominiums and apartments, the Reef project was marketed to decision makers as a classic transit-oriented development. The site sits next to the A Line, a light rail route connecting downtown with Long Beach.

Tenants’ rights groups mobilized to fight the project, saying its luxury offerings would spur nearby landlords to jack up rents or sell their properties to other developers, pushing out families in some of the city’s most impoverished neighborhoods.

Backers of the project insisted the Reef would not displace renters, since it was planned on a series of parking lots. Mark Williams, then a board member with the nonprofit Concerned Citizens of South Central Los Angeles, said the area desperately needed the investment promised by the Reef.

“We’ve been trying with all our might to gentrify our community,” he told the planning commission in 2016. “We’ve been trying to attract working people, wealthier people to our community. We need economic integration.”

Tavitian agreed to put $15 million into an affordable housing fund controlled by Price. Anti-poverty activists, in a pair of raucous City Hall meetings, argued that the contribution fell far short of what the area needed.

Digital signs were a secondary element in the Reef debate. But when the project came up for its first major hearing in 2016, Mayor Eric Garcetti’s appointees on the planning commission seized on the issue, warning that the electronic billboards would end up shining into people’s homes.

Commissioner Samantha Millman pointed out that the panel had rejected digital billboards on another project near the much wealthier area of Hancock Park. “I think that South L.A. deserves the same,” she said during the meeting.

The commission rejected the Reef’s digital billboards, agreeing to permit non-electronic signs on the site’s existing building. But when the project reached the council’s planning committee three months later, Price worked to reverse that decision, allowing electronic signs as part of the larger Reef project.

Price provided the developer a series of other concessions, making the billboards even more lucrative.

According to a city analysis, the councilman allowed the digital signs on the existing Reef building to be twice as big as the planning department recommended. Price also allowed those signs to stay on until 11 p.m. on weekdays and midnight on weekends — later than planning staff had proposed.

In addition, the councilman allowed the three billboards to change images every eight seconds, instead of the one-minute interval recommended by city planners, ensuring drivers would see multiple ads, not just one, as they passed by. And he ensured the digital billboards would be approved with a permit at the Department of Building and Safety, instead of a lengthier review by city planners.

The council backed Price’s changes unanimously. That same month, Ek, Sunkin, Klink and Bai, the City Hall lobbying firm that represented the Reef’s developer, were registered as the co-sponsor of a new political action committee known as the Progressive Growth PAC.

The PAC spent about $103,000 — about three-fourths of it from companies where Tavitian is an owner, a manager or both — on activities aimed at reelecting Price in 2017, according to campaign reports and state business records. The committee paid for campaign mailers, outdoor signs and pre-recorded phone calls to voters from former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.

Those pro-Price advertisements named the committee’s biggest contributors, including Tavitian’s companies. But they made no mention of Tavitian, the Reef or PHR LA Mart, the Reef’s developer.

The average voter would have no idea that those companies were connected to the skyscraper complex, said Nuño, who ran against Price that year.

“That’s dark money,” he said. “That’s where special interests infiltrate democracy.”

Howard Sunkin, who worked for the Ek firm in 2017 and represents the Reef’s developer, did not respond to requests for comment.

After Price won reelection, he and his colleagues finalized the Reef’s sign district, which spelled out the rules governing the electronic billboards. That part of the process caught the attention of federal investigators, who highlighted it in their case against Huizar.

Prosecutors alleged that Huizar and an aide sought to exploit developers’ fears that their plans would suffer if they didn’t make campaign donations. Among those targeted was a firm investigators called “Company I,” which had a hearing on its sign district scheduled for Oct. 24, 2017, according to the indictment.

That was the date that a committee headed by Huizar was set to review the Reef’s sign district.

In their indictment, investigators said Huizar kept a spreadsheet that showed that Company I had pledged $25,000 to an unnamed political action committee. But prosecutors did not say whether the company followed through.

The Times was unable to identify a $25,000 donation from the Reef developers to any of Huizar’s committees.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.