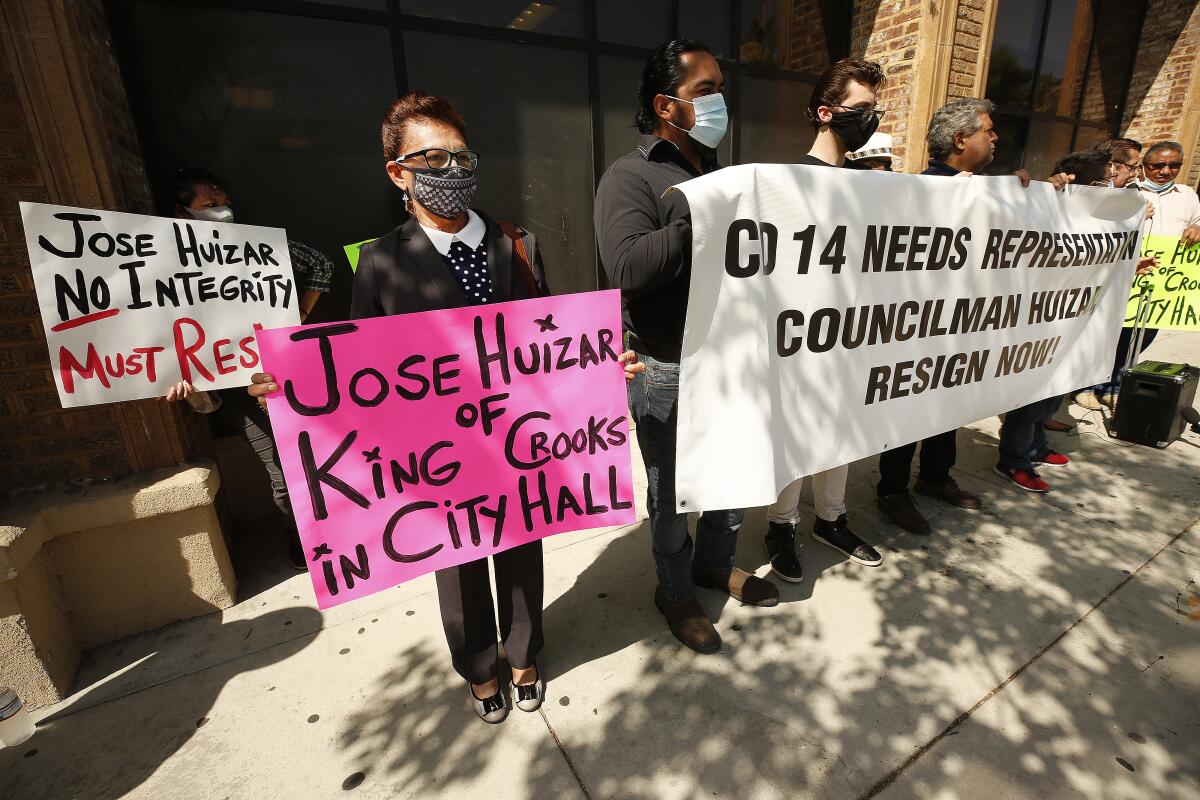

L.A.’s corruption probe involves developers, a councilman — and his 80-year-old mom

- Share via

The corruption case against Los Angeles City Councilman Jose Huizar is spangled with influential City Hall figures — wealthy real estate developers, well-connected lobbyists and a campaign fundraiser known for raking in cash for politicians.

But investigators have also turned the spotlight on a less likely figure in a pay-to-play scandal: an elderly woman who emigrated from Zacatecas, Mexico, once worked in a meatpacking plant, and has lived in a modest home in Boyle Heights.

Isidra Huizar, the 80-year-old mother of the embattled councilman, is one of the unnamed figures mentioned in the sprawling case, according to three sources familiar with the investigation.

Federal prosecutors have alleged, without mentioning her by name, that Isidra Huizar helped her son launder bribe money that he received between 2014 and 2017. Huizar’s mother, identified only as Relative A-2, repeatedly received cash from her son, then used the proceeds to pay his expenses, according to a 116-page affidavit filed the week that Huizar was arrested.

Isidra Huizar, in an interview with The Times, confirmed that she had been questioned by investigators who wanted to know about her son and his money. But she denied engaging in money laundering, saying she was only safeguarding the cash. She described the allegations against her son as untrue.

“They’re accusing him of so many things he didn’t do,” Isidra Huizar said, speaking in Spanish. “It’s not true what they’re saying in the newspapers and on the news.”

Huizar’s mother is not the only family member to come under scrutiny during the investigation. The councilman’s wife, Richelle Huizar, is mentioned repeatedly in cases targeting former Huizar staffer George Esparza and other figures who have struck plea deals in the probe.

Federal prosecutors have also focused on financial transactions allegedly made by Salvador Huizar, the councilman’s brother, who is listed in the criminal affidavit as Relative A-3, according to a source familiar with the probe.

Prosecutors said Relative A-3 also helped the councilman launder bribe money and lied about his involvement when he was initially questioned by FBI agents in 2018, according to the criminal complaint.

Edward Robinson, a lawyer for Salvador Huizar, declined to answer questions about the federal case, including the allegations in the affidavit. Robinson said he had instructed Salvador Huizar not to talk to anyone about the case.

Neither Isidra nor Salvador Huizar has been arrested or publicly charged. But this is not the first indication that their financial transactions are part of the probe. Two years ago, the FBI sought their bank records in a search warrant that probed for evidence of possible crimes including bribery and money laundering.

Last month, when Councilman Huizar was released from federal custody, a judge instructed him not to communicate with any witnesses or victims — but carved out an exception for Isidra, Salvador and Richelle Huizar.

The criminal complaint indicates that Isidra and Salvador Huizar gave investigators information under proffer agreements, an arrangement in which prosecutors agreed not to use that information against them.

Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson said such pacts, also known as “queen for a day” agreements, can be a way for a possible target in a case to make the argument that “we’re better as your witness than as one of your defendants.”

Federal investigators alleged in the complaint that Jose Huizar funneled cash bribes through his family members, who put the money into their own accounts and then paid his credit card bills, property taxes and other expenses, including the interest on a bank loan that allowed the councilman to settle a sexual harassment lawsuit filed by one of his aides.

Prosecutors said Huizar gave his mother more than $108,000 in cash between January 2014 and September 2017; she paid roughly the same amount directly or indirectly to Huizar, according to information in the criminal complaint.

Investigators alleged that the councilman also provided cash to his brother, who then paid roughly $130,000 directly or indirectly to him, according to information in the criminal complaint.

A federal investigator examined bank records and watched surveillance footage of Isidra Huizar depositing an envelope with “a large sum of cash,” according to information in the criminal complaint.

In November 2018 — the same month that FBI agents raided Huizar’s home and offices — the councilman’s mother and brother were interviewed by federal agents and falsely denied that Huizar had given them cash, according to information in the criminal complaint.

Both were interviewed again earlier this year and admitted that they received cash from the councilman, prosecutors said in their filing. Huizar’s mother said that he had asked her for blank checks that he used to pay his bills, according to information in the criminal complaint.

Salvador Huizar also told investigators that Huizar asked him to cover his expenses, according to information in the filing. And he admitted to lying to federal agents about the financial transactions during his earlier interview, prosecutors indicated in the criminal complaint.

In an interview with The Times, Isidra Huizar said that she had not lied to investigators, arguing that they hadn’t properly explained their question.

She said that when she was first asked if Jose Huizar had given her money, she initially said no, because the money wasn’t meant for her. Later, she said, the investigators clarified that they were asking if Jose gave her money to hold onto.

“That’s different,” Isidra Huizar said in Spanish. “And that’s why at first I said no, and later yes.”

Isidra Huizar said the money that Jose Huizar had provided was for school tuition for his children.

Both Isidra and Salvador Huizar have been registered to vote for years at the same address in Boyle Heights — a modest 464-square-foot home owned by the Huizar family for decades, according to city and county records. In an interview, however, Isidra Huizar said that Salvador did not live with her.

Isidra Huizar has figured prominently in the councilman’s story. She has appeared on his campaign mailers celebrating his graduation from Princeton and holding one of her granddaughters.

In an interview with the Immigrant Archive Project, the councilman said his mother and father worked constantly even as they raised six children. Her jobs included working at a meatpacking company, Jose Huizar said. And last year, Jose Huizar featured a photo of him and his mother on his Facebook page on Mother’s Day, praising her as “the rock of our family.”

Isidra Huizar told The Times that she believed the family was being subjected to discrimination as Latinos, because “they’re saying things that aren’t true.”

Repeated references to Richelle Huizar in the case have raised questions about whether she could be called to testify in a case targeting her husband. Prosecutors alleged in the criminal complaint that the councilman held meetings with his wife, partners at her law firm, and developers pursuing projects in his district. During the meetings, Huizar urged developers to hire his wife’s firm, investigators alleged in the criminal complaint.

Legal experts say a married person can choose to testify against their husband or wife, waiving their “spousal privilege” in court. But if they do, the other spouse can block them from revealing marital communications — private conversations or other exchanges as a couple.

However, experts said that would not stop the spouse from testifying about other facts in a criminal case.

There is no similar privilege for testimony by parents or other family members, Levenson said. That issue came up during the investigation of President Bill Clinton, Levenson said, when Monica Lewinsky was aghast to discover that her mother could be compelled to testify.

Times staff writer Joel Rubin contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.