California braces for a spike in coronavirus deaths as infections soar. But how bad will it be?

- Share via

New coronavirus cases roughly doubled in California over the last month. Hospitalizations have soared 88%, filling some medical centers close to capacity.

Now, public health officials are bracing for the grimmest phase of the cycle: a spike in COVID-19 fatalities.

So far, new deaths have remained relatively flat in California even as cases have surged. In the last six weeks, the state has recorded an average of 436 weekly coronavirus deaths, down from the previous six-week average of 510 weekly deaths, according to a Los Angeles Times data analysis. But deaths are a lagging indicator, and many experts predict an increase in the coming weeks.

California has seen far fewer coronavirus fatalities than some hot spots across the country, recording more than 6,400 deaths, compared with more than 32,000 in New York and 15,000 in New Jersey.

How much the death toll in California will rise is the subject of some debate. This new wave of infections is increasingly being driven by younger people, while outbreaks in skilled nursing facilities have slowed. For that reason, it’s possible that fewer of the recent cases will result in deaths.

“It’s hard to say because right now, it’s this cloud of information that needs to sort itself out,” said Dr. Neha Nanda, healthcare epidemiologist and medical director of infection prevention at Keck Medicine of USC.

Gov. Gavin Newsom said Monday said the surge in coronavirus cases hitting California was due in part to younger people who might believe “they are invincible” but nonetheless are becoming sick from COVID-19.

But others on the front lines say the younger COVID-19 demographics won’t necessarily result in a decreased death toll. Adrienne Green, chief medical officer for UC San Francisco Medical Center, said she is worried about the current wave of infections among younger people leading to a subsequent wave for older people who have interacted with them.

“Perhaps there might be a lull in the death rates and then [they] catch up,” Green said. “I think it’s going to be a wave up and down.”

Answers should come soon. Experts say it can take three to four weeks after exposure to the virus for infected people to become sick enough to be hospitalized, and four to five weeks after exposure for some of the most vulnerable patients to die from the disease.

California recorded nearly twice the number of coronavirus cases in June as it did in May — 119,938 versus 61,694, according to a Times data analysis. Yet the number of deaths declined, with 2,128 people dying in May and 1,915 in June.

Gov. Gavin Newsom said Monday that while a higher percentage of coronavirus tests are confirming infections, “we’re not seeing a commensurate increase yet in mortality.”

More younger people are also testing positive for the virus, a trend that has become apparent as the economy has reopened and working-age adults returned to jobs and resumed social gatherings.

Early in the pandemic, in March, about half of California’s new infections were identified among people ages 18 to 49, a Times data analysis found. In June, as the number of new cases began to climb sharply, that share increased to nearly 62%. So far in July, roughly 65% of new infections have been diagnosed among those 18 to 49. That’s despite the fact that just 45% of Californians fall into that age range.

“These are individuals who tend not to be as likely to get serious disease or require either hospitalization or to die from COVID-19,” said Timothy Brewer, professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA. “So particularly the 18- to 50-year-old age group is a group that has relatively low mortality rates, but there has been a big surge in infections.”

Meanwhile, outbreaks in skilled nursing and other long-term care facilities have slowed. That appears to be particularly true in Los Angeles County, which is home to nearly half the state’s cases and more than half the deaths.

In early May, L.A. County was reporting an average of 25 daily coronavirus deaths out of nursing home residents. By late June, the average daily death toll from nursing homes was around 10, Barbara Ferrer, the county health director, said last week.

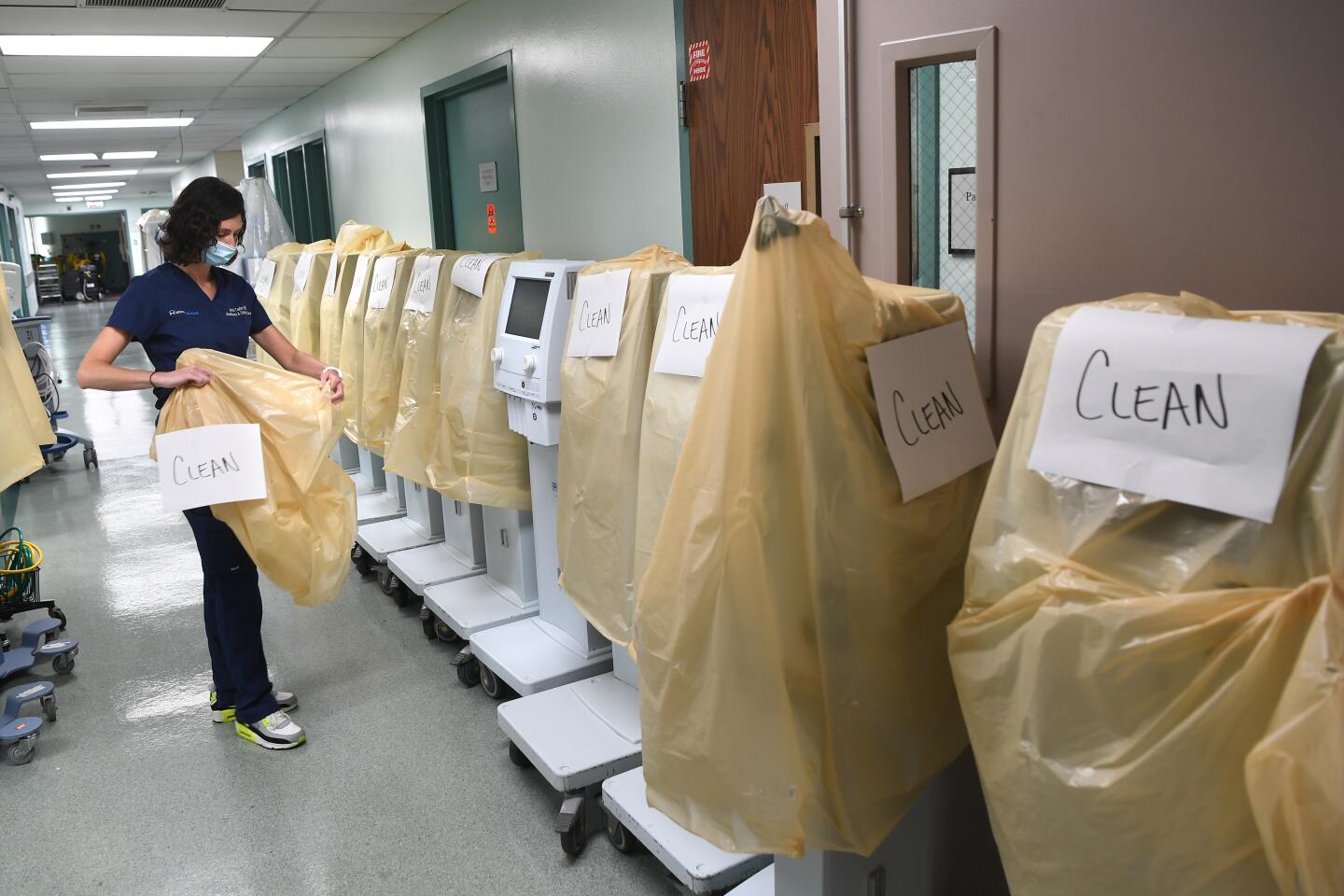

Officials have said better use of personal protective equipment, such as masks, gowns and gloves, and increased testing, has helped reduce the impact of the pandemic on skilled nursing facilities.

Brewer said he suspects the decline in care facility outbreaks is having a beneficial effect on overall mortality rates, as residents of skilled nursing and assisted living facilities account for 49% of the state’s total COVID-19 deaths.

Nick Jewell, a UC Berkeley biostatistics expert who has tracked the pandemic, said the steady mortality rate may also reflect that those who were most susceptible to the virus — the elderly and the infirm — have already succumbed to it.

“To be crude, you wouldn’t expect as many nursing home deaths today as you would two or three months ago because the susceptibles in the nursing homes have been picked off,” said Jewell.

Improvements in the treatment and care of COVID-19 patients also may have made a difference, as doctors have learned more about how to treat the virus.

Medical staff have gotten better at managing the ventilation and oxygenation of critically ill patients, learning to do things such as positioning them on their bellies instead of on their backs, Brewer said.

Physicians also say they are generally intubating less frequently. Intubation — inserting a breathing tube down a person’s throat — can cause an array of complications, but doctors have been able to choose other options first, instead of quickly intubating a person who is struggling to breathe.

Dexamethasone, a corticosteroid that has been shown to improve survival in patients who require oxygen or mechanical ventilation, is now in standard use in hospitals across California, Brewer said. Remdesivir, an antiviral that has been linked to improved outcomes, is also being widely used, he said.

More than 130 labs around the world are working to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. But what would it take to vaccinate everyone by early next year?

UCSF’s Green attributes better fatality rates to medications including Remdesivir but said the drug may soon be harder to come by.

Some point out that the declining numbers do not take into account the well-documented racial disparities seen in both infections and outcomes of COVID-19 cases. Across the country, researchers are finding that Black and Latino people are hit harder, and have worse survival rates than white counterparts.

In California as of Sunday, Latino people accounted for 55% of coronavirus cases and 42% of deaths, while making up about 39% of the state’s population, according to data from the California Department of Public Health. Black Californians account for 9% of the state’s deaths, while making up about 6% of the overall population. But even those figures may be low — 35% of cases are missing race and ethnicity data.

Stephen Lockhart, chief medical officer of Sutter Health, said it is too soon to know if reopening has made those disparities worse. Many of those who have worked through the pandemic or returned to work in recent weeks at jobs including retail, restaurants, agriculture and service sectors are people of color, he and other experts pointed out. Lockhart said that although the data are not yet available on how they are faring, he would “be surprised if that were not the case” that those workers of color will be hard hit in coming weeks.

“That is just my conjecture as a Black man seeing what I am seeing and my overall intuition,” Lockhart said. “I am imagining that the gap has widened.”

Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford, said the demographics of the epidemic have “really changed” in recent months.

“Now it has become much more in minority communities, much more blue-collar workers,” Maldonado said.

On Saturday, Maldonado did free testing in a low-income Silicon Valley neighborhood that is predominantly Asian and Latino. After testing about 300 people, she found about 3% were positive — what she considers a difficult rate to contain, despite higher rates in other parts of the state and country, and one coupled with health and wealth disparities that can increase the severity of the virus..

“We know that these are populations that have real health equity and access problems,” Maldonado said, pointing to more risk factors such as diabetes, more crowded living spaces and less financial ability to take time off work.

Some also fear that it’s only a matter of time before California sees a surge in COVID-19 deaths to match the increase in cases and hospitalizations. Many experts believe the increasing infections began around Memorial Day, meaning a corresponding increase in deaths may begin soon. They also point out that recent Independence Day celebrations could bring another bounce in coming months.

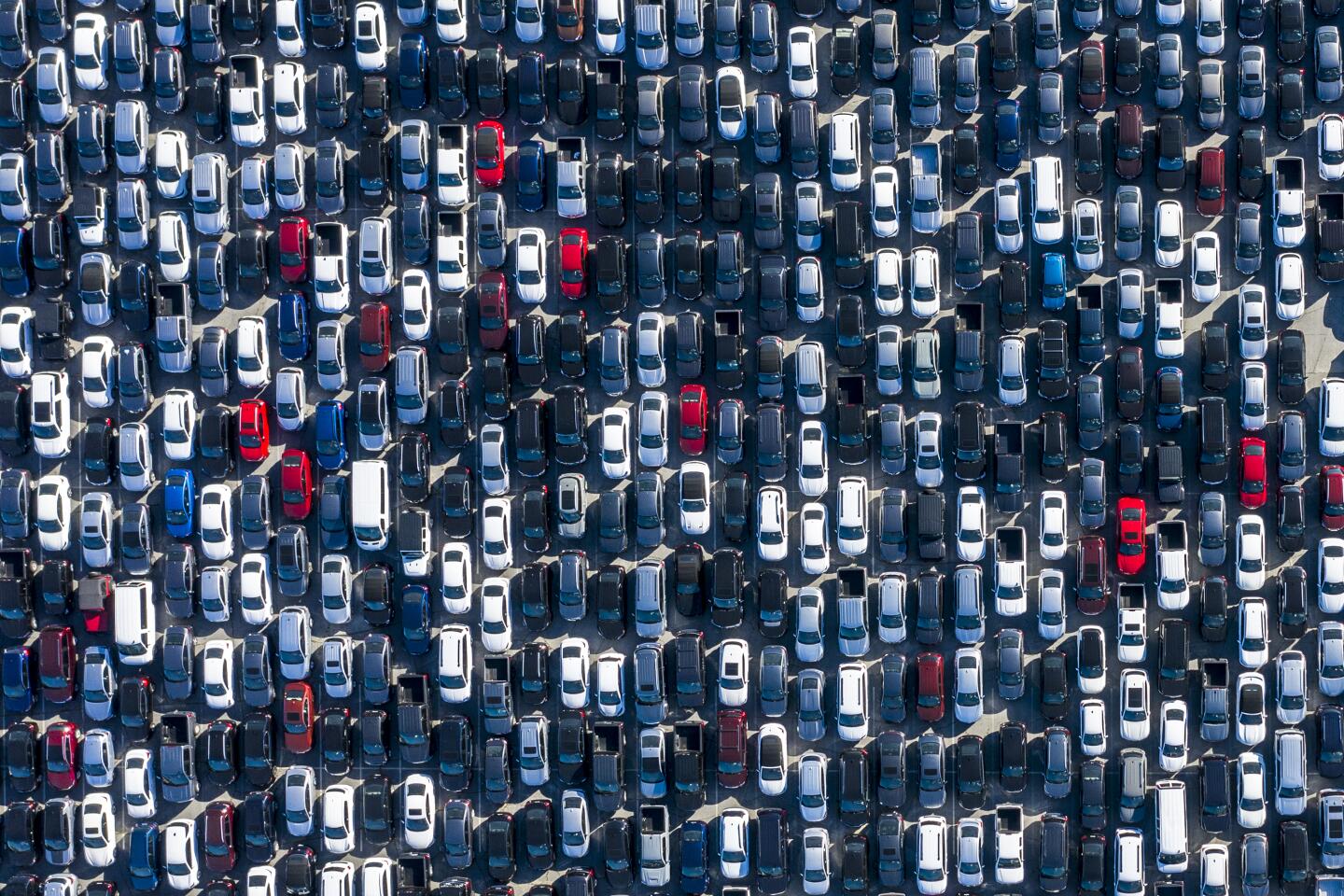

On Sunday, there were 5,790 people hospitalized in California with confirmed coronavirus infections. That’s an 88% increase from that number on June 5, when there were 3,072 hospitalized.

L.A. County on Sunday broke a record for the largest number of hospitalized patients with confirmed coronavirus infections. There were 1,969 such patients in hospitals in the county on Sunday; the previous record was on April 28, when 1,962 were in the hospital.

Jewell cautioned that “things are changing rapidly in the state.” He said that California, though not as bad as states such as Texas — where hospitals are already facing capacity issues — remains in “dangerous waters,” and he expects July to be a “real gut check.”

Newsom vows to crack down on restaurants and bars that ignored restrictions over the July 4 weekend. Some critics say it is too little, too late.

There are also concerns that the younger people who are currently testing positive at a higher rate and also tend to have a higher level of mobility will eventually transmit the virus to more people, including those who are more vulnerable, driving deaths even higher.

“It’s not until the first group [of infected individuals] goes out and infects the next larger group and gets a bit exponential” that we see those deaths, said a nurse who works in an intensive care unit in L.A.

“It’s the calm before the storm — I have no doubt,” she added.

Times staff writers Ben Welsh, Colleen Shalby, Iris Lee and Sandhya Kambhampati contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.