LAPD responds to a million 911 calls a year, but relatively few for violent crimes

- Share via

More than a million times last year Los Angeles police officers were dispatched on calls for help.

Contained within that huge volume of 911 calls is a defining aspect of policing in modern America: The job has expanded over time to include far more than fighting crime.

Although armed with weapons and the unique authority to use force, cops often are sent to resolve problems that should not require their coercive powers. Family fights, episodes of mental illness, complaints of loud parties, and dogs running loose are all part of the job.

Police, in fact, spend relatively little time responding to reports of violent crime, despite that being widely viewed as a core police function, a Los Angeles Times analysis found.

Of the nearly 18 million calls logged by the LAPD since 2010, about 1.4 million of them, or less than 8%, were reports of violent crimes, which The Times defined as homicides, assaults with deadly weapons, robberies, batteries, shots fired and rape. By contrast, police responded to a greater number of traffic accidents and calls recorded as “minor disturbances,” The Times found.

The Times included in its analysis categories of 911 calls and calls initiated by police officers.

The extensive role of police in American life has come under scrutiny in the wake of the killing of George Floyd and other recent deaths of Black Americans at the hands of police. Fury over the killings and, more broadly, a long history of police abuse of Black people have led not only to demands for police to be better trained and more restrained in their use of force, but that their extensive presence in American life be cut back as well.

“The only way to guarantee police violence does not occur is to avoid the encounter altogether,” said Philip McHarris, a sociologist whose work focuses on policing and who has argued for the need to dramatically reduce police presence.

Deluged by demands for cuts in police spending, the L.A. City Council votes to take the LAPD down to 9,757 officers by next summer.

Any such rethinking of policing in America will include an examination of how officers currently spend their time. To better understand what the job looks like now, The Times analyzed the decade of LAPD calls for service. The figures underscore both the possibilities and the challenges of redefining what police do.

Reaching agreement on how to curtail the job of policing will be difficult.

Leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement in Los Angeles and others are calling for a wholesale replacement of police with an expansive network of unarmed professionals including social workers and mental health experts.

Police officials and powerful unions representing rank-and-file officers, meanwhile, are opposed to any significant cuts to the size, massive budgets and influence that police departments have steadily amassed over the decades.

And with polls showing Americans support changes, but are torn on how far reforms should go, elected officials in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York and elsewhere are searching for some middle ground. Last week, the Los Angeles City Council voted to cut $150 million from the LAPD’s roughly $1.85-billion annual budget, but did not impose any changes on what the city’s police are allowed to do.

By far, the most common types of police work recorded by the LAPD were stops of drivers and pedestrians that officers elected to make on their own for perceived violations. Each year over the past decade, Los Angeles police have made between 550,000 and 950,000 such stops, according to The Times’ review.

These stops have contributed heavily to the distrust and anger Black Americans feel toward police as studies have found repeatedly that police target Black people for stops at disproportionately high rates compared to other races and ethnicities.

Last year, for example, a Times investigation found that a special unit of LAPD officers stopped Black drivers at a rate more than five times their share of the city’s population.

Dramatically scaling back the frequency of these stops could lead to a meaningful change, McHarris said.

“A big piece of this is removing police from traffic safety,” he said. “Much of police violence starts during traffic stops.”

The idea of removing police from traffic enforcement is under consideration in New York City and in Los Angeles, where members of the city council proposed replacing police officers with staff from the city’s transportation department or automated technology for enforcement of many traffic laws.

Although little consensus has emerged over types of calls that should be taken from police, there is some agreement around the idea that calls involving people with mental illness could be better handled by specially trained, unarmed professionals.

LAPD Chief Michel Moore expressed support for the idea recently, and the department is planning to begin diverting some suicide calls to a phone line run by a mental health organization.

But removing police from all mental-health-related calls would reduce the LAPD’s overall footprint in the city only minimally, since they accounted for less than 2% of all calls, according to the analysis. The Times included 911 calls of someone possibly being suicidal in the tally of mental-health-related calls.

Mental health calls also illustrate some of the challenges for Los Angeles or other cities that attempt to overhaul their police departments, experts cautioned.

In more than 324,000 mental-health-related calls over the past decade, at least 9% of the time — 29,000 calls — the person reporting the incident indicated to the 911 dispatcher that the mentally ill person was acting violently, according to how the calls were coded by LAPD dispatchers.

It is unknown from the available data whether these calls were resolved peacefully or if the presence of armed police officers, who receive little training in how to help someone suffering from mental illness, escalated already tense scenarios and resorted to using deadly force as they have several times in recent years.

Nonetheless, as elected officials in Los Angeles and elsewhere contemplate sending psychologists or social workers instead of police when people with mental illness are in distress, the LAPD data underscore the stark reality that some of those calls will be violent.

“We need to decide how much risk as a society we’re willing to take that we might send someone into a situation that turns violent,” said Steve Matrofski, a criminologist who has studied the structures and effectiveness of police departments. “But we also must decide if we are willing to continue to take the risk that sending police into some situations actually make things worse. Where is the balance?”

That tension is embedded in other types of calls as well.

Last year, for example, LAPD officers responded to about 170,000 reports of disturbances, a broad category that over the past decade has accounted for about 9% of all of LAPD’s calls for service.

A breakdown of the dispatch data indicates the vast majority of those calls did not include a reference to violence and could have possibly been handled by people other than police. But about 17% of the time the caller to 911 referred to a weapon or fight, according to The Times’ analysis.

In a similar vein, police did little more than direct traffic at many of the 70,000 traffic collisions they responded to last year, but others involved possible drunk driving and hit and run investigations.

In comments last week to the civilian board that oversees the department, Moore alluded to the complexities of parsing which calls should and should not be the domain of police.

Calling for “a multi-phase approach” to mental health calls, Moore envisioned a system in which “a clinician, perhaps a medical professional, will go and handle that call, another one in which there needs to be a law enforcement presence in concert with the clinician ... and then one in which the life challenge or emergency is so great or so significant that we dispatch police first, and then quickly followed behind them is clinician support once the scene is safe.”

The city would need to boost its ranks of mental health professionals to make such a plan possible, Moore and others have said. And it remains to be seen how the high-stakes, on-the-spot decisions of whether to send police officers to a call will be made.

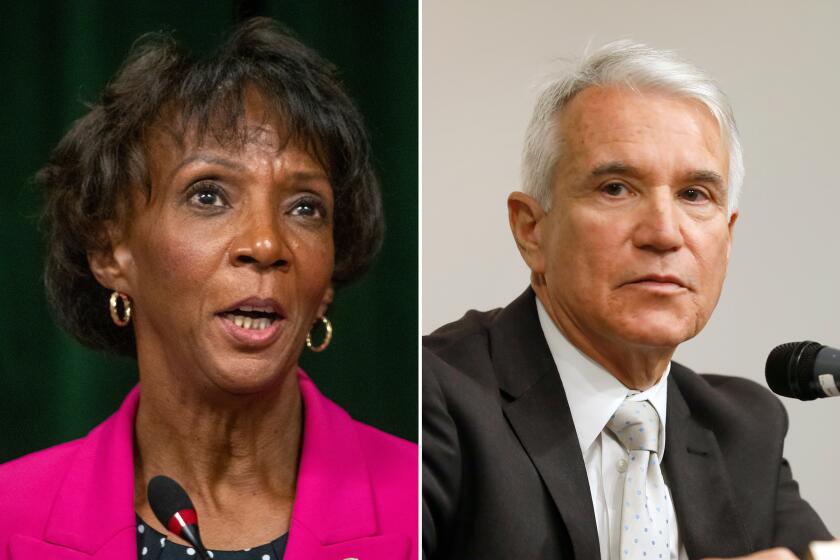

Protests over police brutality and criminal justice reform intensify race for L.A. district attorney

The battle between Jackie Lacey and George Gascón to lead the nation’s largest local district attorney’s office is already being influenced by the fallout of national calls to change American policing.

Matrofski and others said cities will need to improve their collection and use of data, such as the history of calls at a particular address, to minimize the chance of mistakes.

Some categories of calls appear less complicated. Nearly 66,000 times last year, police were called on to respond to minor disturbances, which included complaints of fireworks, loud music and car alarms. And thousands of times each year police are summoned to referee squabbles between family members, tenants and landlords and others.

These types of quality of life issues could be handled by something along the lines of the unarmed, uniformed “police support officers” used in the United Kingdom, said Alex Vitale, a sociologist at Brooklyn College who has argued for the need to dramatically scale back police responsibilities.

“Police are not social workers, they are violence workers — they are authorized to use violence in a way no other person is allowed and their authority is derived from this power,” Vitale said. “We’ve turned over all these problems to police because there was no one else left, but we need to open our minds to other options.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.