See how your favorite beach ranks in the latest pollution report card

- Share via

As coronavirus beach restrictions continue to complicate summer plans, Californians have at least one thing to look forward to: Most of the coast is much cleaner than in years past.

In an annual survey of more than 500 beaches, Heal the Bay reported Tuesday that 92% of the state’s beaches had logged good water-quality marks between April and October of 2019 — a notable improvement from prior years, when heavy winter rains washed trash, pesticides, dog poop, bacteria and automotive fluids, as well as microplastics, into storm drains and out to the ocean.

A relatively dry year has meant less polluted beaches — particularly in Southern California, where Orange County had 20 of the state’s cleanest beaches.

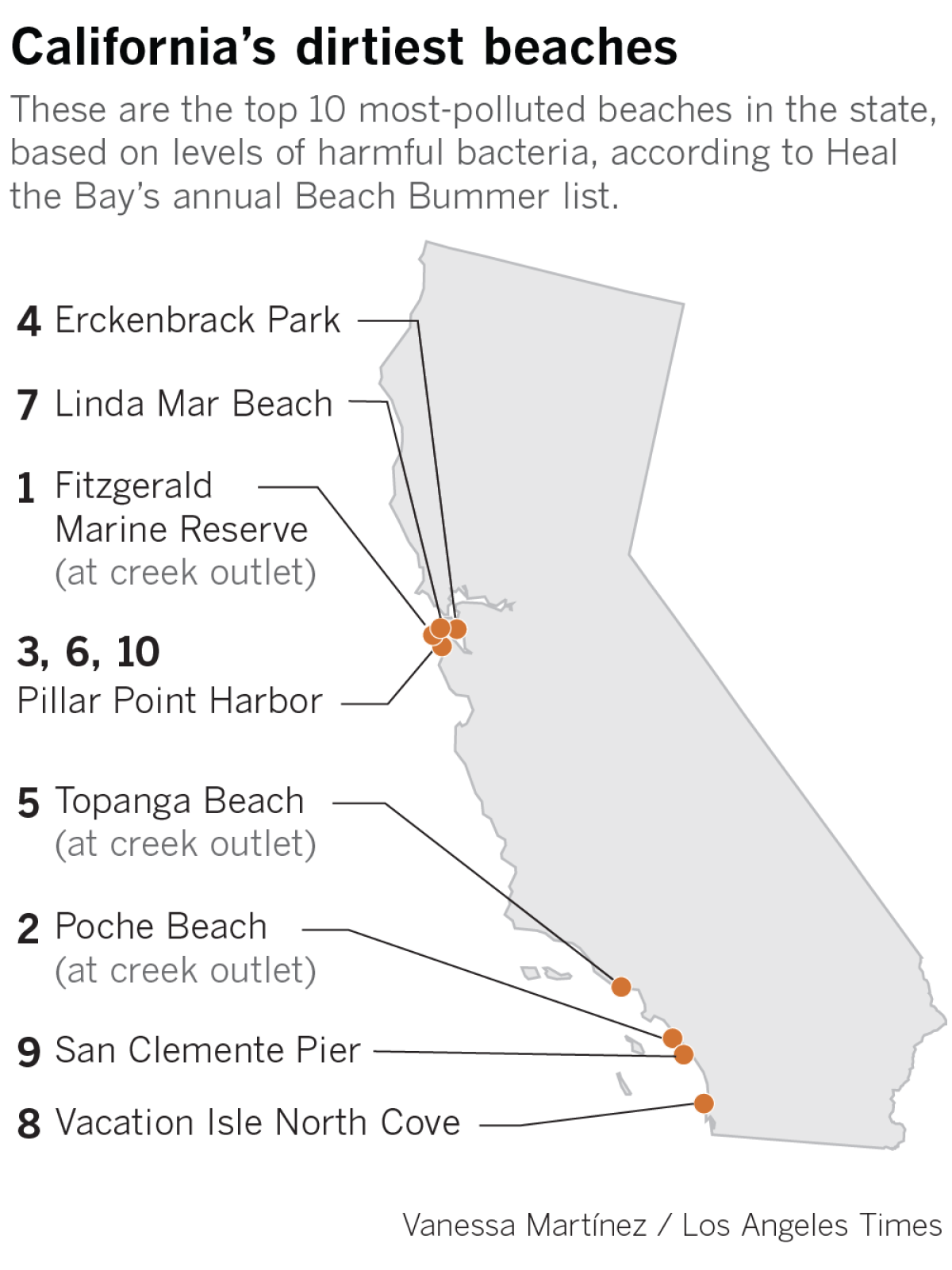

Still, the environmental group noted some stubborn (and surprising) pockets of pollution along the coast. Six of the state’s 10 dirtiest beaches this year are in San Mateo County — an unusually high number for this part of the Bay Area.

The four others on the Beach Bummer list are well-known trouble spots in Southern California: Poche Beach at the creek outlet and San Clemente Pier, in Orange County; Topanga Beach, in Los Angeles County; and Vacation Isle North Cove, in San Diego’s Mission Bay.

The annual “report card,” now in its 30th year, assigns letter grades, A+ through F, based on routine beach water-quality sampling conducted by county health officials, sanitation departments, and state and tribal agencies. Water samples are analyzed for three fecal-indicator bacteria that show pollution from numerous sources, including human and animal waste.

Because the raw data and formatting vary county to county, Heal the Bay began compiling and translating the information each year into a simple letter grade. The State Water Resources Control Board endorses this report, which has influenced significant research over the years and pushed California to become a leader in clean-water monitoring.

Broken down simply, the higher the grade, the better the water quality. The lower the grade, the greater the health risks. Swimming at a beach with a grade of C or lower greatly increases the risk of skin rashes, ear and upper respiratory infections, and other illnesses such as the stomach flu.

California’s dirtiest beach this year came as a surprise: Fitzgerald Marine Reserve, by the San Vicente Creek outlet in San Mateo County. The reserve generally has good summer water quality and has never appeared on the bummer list before.

Linda Mar Beach at San Pedro Creek, in Pacifica, made the top 10 for a third year in a row; Erckenbrack Park, in Foster City, came in at No. 4; and three locations in Half Moon Bay’s Pillar Point Harbor were considered among the state’s dirtiest beaches this year.

Luke Ginger, a water quality scientist at Heal the Bay, said there didn’t appear to be a single sewage spill or event that could explain why so many beaches in San Mateo County were more polluted than normal this year.

Officials in the area could look for leaky pipes, he said, and conduct some sort of source investigation — going up the watershed and through storm drains, for example, to find out where the pollution might be coming from.

After another back-to-back cold front that pelted rain, heavy snow and even a tornado warning down onto Southern California, here are some precautions and commonly asked questions about whether it’s safe to go to the beach.

These scarlet-letter grades have inspired a number of projects over the years. Cowell Beach in Santa Cruz, a chronic top 10 bummer, dropped off the list this year after city officials and environmental groups teamed up to repair sewer lines and divert polluted water before it reached the ocean. They also found ways to deter birds from nesting and pooping at the pier.

In Long Beach, officials improved water circulation at Colorado Lagoon and removed contaminated sediment. Similar improvements were made at Avalon Harbor, which used to be one of the state’s most polluted beaches.

Across Southern California, grades this year were good overall. Orange County had 20 beaches that received an A+ grade every week, during all seasons and weather conditions, and San Diego County had 10, including five in Carlsbad, for a second year in a row.

Three beaches in Los Angeles County also made Heal the Bay’s “Honor Roll”: Palos Verdes Cove and Palos Verdes Long Point, and Redondo State Beach at Topaz Street. In Ventura County, 100% of its beaches received A grades for a second summer in a row.

Beach data weren’t always this clean or transparent. Thirty years ago, swimmers would get sick, especially after it rained, but few people knew when or where to avoid the beach.

Mark Gold, Heal the Bay’s first staff scientist, still remembers a freak thunderstorm in the summer of 1989 that knocked out a Venice sewage pumping station. The public swam in that dirty water all weekend, he said, and didn’t hear about it until many days later.

“That, to me,” he said, “was the last straw.”

He drafted the beach report card and, with a team of scientists, conducted an epidemiology study that connected for the first time just how sick people could get from swimming in water polluted with urban runoff. The constant drumbeat of poor beach grades pushed the state to require standardized monitoring and public notification of sewage spills.

The state has since funded significant research and invested $100 million in Clean Beach Initiative grants — many prioritized based on the beach report card rankings. Officials also now use the data to help determine Clean Water Act violations, and real estate advertisers have even used A grades to promote beachfront homes.

Monitoring methods and real-time reports have also improved, and the survey has expanded to beaches in Oregon and the state of Washington. Next year, the report will include three popular beaches in Tijuana that are regularly affected by raw sewage: El Faro, El Vigia and Playa Blanca.

“It really grew into something that we never expected,” said Gold, who is now Gov. Gavin Newsom’s deputy secretary for coast and ocean policy. “An entire generation of people who are going into the water right now, they have no idea how horrible the water quality was at the beach during the 1980s.”

Today, storm drain runoff remains the largest source of pollution for California’s beaches. Unlike our sewage, which is usually filtered through treatment facilities before it’s discharged, most of this dirty water flushes straight into the ocean through a network of storm drains and concrete-lined rivers.

A good rule of thumb is to wait 72 hours after it rains before going into the ocean, and to stay at least 100 yards away from storm drains, piers or enclosed beaches with poor water circulation.

Shelley Luce, president of Heal the Bay, says the growing public awareness has been remarkable, but the work is never over. She points to the recent enforcement rollbacks by the Environmental Protection Agency, which threaten to undo decades of progress.

Citing coronavirus safety concerns, the EPA has temporarily suspended enforcement of environmental laws.

“The federal administration used the COVID pandemic as an excuse to roll back environmental protections in a major, major way,” she said. California even loosened some of its own monitoring requirements, citing the limitations posed by stay-at-home orders.

“People need to stay vigilant and understand that we need to protect our planet and our environment and our clean water,” she said, “regardless of what else is going on.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.