In the Antelope Valley, a history of racism fuels suspicions over Robert Fuller’s death

- Share via

Arthur Calloway, a Black man, was pulled over so many times in Lancaster by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies — asked to step out of his car and handcuffed while it was searched with little or no explanation — that he started avoiding certain streets.

In the Antelope Valley, he said, he has been confronted multiple times by racist skinheads who told him he doesn’t belong.

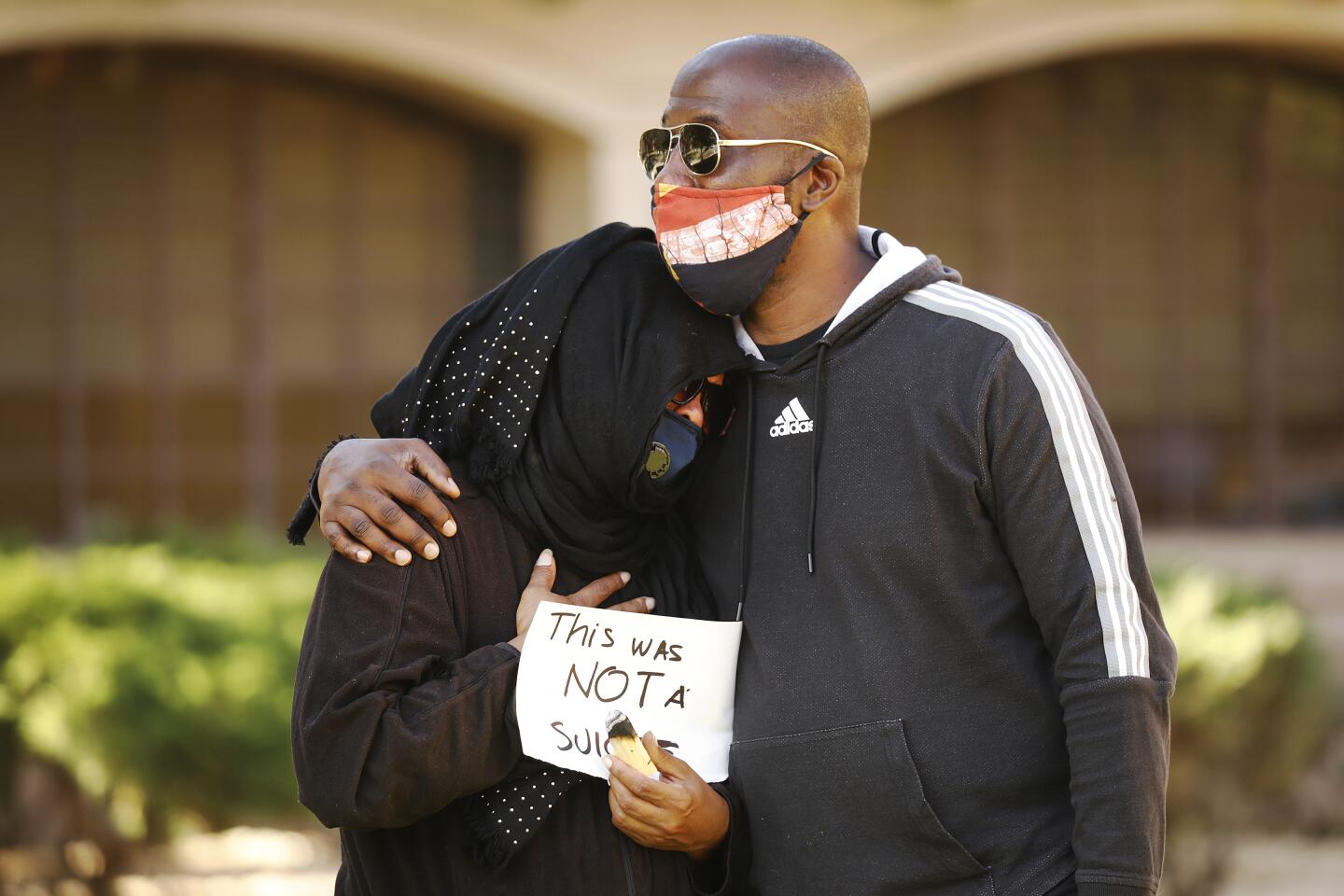

And so, after authorities were quick to say that the death of Robert Fuller — a 24-year-old Black man found June 10 hanging from a tree near City Hall in neighboring Palmdale — was likely a suicide, Calloway was immediately skeptical.

- Share via

On June 10, Robert Fuller’s body was found hanging from a tree outside Palmdale City Hall. His death came in the middle of the George Floyd protests and a week after Malcolm Harsch, another Black man, was found hanging from a tree in Victorville, less than 50 miles away. Their deaths shed light on the concerning rise in suicides among Black Americans.

His heart sank when he went to the site two days later and saw no “crime scene” tape around the tree and someone mowing the grass nearby, as if nothing had happened. He thought of his own 20-year-old son.

“I wish some of the people who say ‘all lives matter’ actually believed it,” said Calloway, a 39-year-old Air Force veteran and president of the Democratic Club of the High Desert. “If a cop was found in a tree in Palmdale, there would be 600 cops scouring the neighborhood looking for answers.”

In the Antelope Valley, which has a substantial Black population, a history of racism has fueled deep suspicions over Fuller’s death, which came after weeks of nationwide protests over the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white Minneapolis police officer.

Jamon R. Hicks, an attorney for Fuller’s family, told The Times it was troubling that the Sheriff’s Department did not initially investigate the death as a homicide, given the current protests over racial injustice and “the fact that this is a city that has had a history of racial tension and conflict.”

“Given that I’m an African American male, our first thought in our community when you see a Black man hanging in a tree is not a suicide,” Hicks said. “Our first thought brings us back to a dark time in history where we see public lynchings to send a message.”

Five years ago, Los Angeles County reached a settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice over allegations that sheriff’s deputies had systematically harassed and discriminated against Black people and Latinos in Lancaster and Palmdale. Some of the worst abuses included surprise, military-style sweeps of federally subsidized Section 8 housing, in which armed deputies accompanied housing authorities to look for violations of housing rules, causing some to be evicted.

Federal investigators also found that Black people were much more likely to be stopped and searched than other residents and that deputies had used excessive force against handcuffed detainees.

“The trust isn’t rebuilt,” Calloway said.

On Monday, L.A. County Medical Examiner-Coroner Dr. Jonathan Lucas said investigators made their initial assumption because of “the lack of any evidence” of foul play.

“He was hanging, and there was no other information to suggest that there was foul play at the time,” Lucas said.

At the scene, authorities found no chair or anything else that could have been climbed upon. Investigators recovered a phone, items in Fuller’s pocket and a backpack.

Sheriff’s homicide investigators now plan to survey the area for surveillance video, conduct a forensic analysis of the rope and knot structure and research Fuller’s medical history.

State Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra said his office was sending independent investigators to Palmdale to review the sheriff’s investigation and potentially conduct its own.

An FBI spokeswoman said Monday that the agency would monitor the Palmdale investigation, as well as the May 31 hanging death of Malcolm Harsch, another Black man, near the city library in Victorville.

When asked about racial tensions in the Antelope Valley at a news conference this week, Sheriff Alex Villanueva said reforms enacted since the 2015 settlement “are working” and require additional funding.

“I think, if you look at the big picture, people trust what the Sheriff’s Department does, by and large,” Villanueva said. “And I know the recent events behind the murder of George Floyd cause a lot of people to rethink their relationship with local law enforcement, but we’ve been at this for 170 years, and we have longstanding ties. We are part of the community.”

But emotions have remained raw. At a news briefing Friday, Palmdale City Manager J.J. Murphy, who is white, acknowledged, “Maybe we should have said it was ‘an alleged suicide.’” Then he added: “Can I also ask that we stop talking about lynchings?”

The audience erupted with cries of “Hell, no!”

The sunbaked, high desert cities of Lancaster and Palmdale — split along Avenue M but nearly indistinguishable — have undergone dramatic growth and demographic change in recent decades.

In 1990, the Black population of the two cities combined was about 7%. By 2018, it had risen to nearly 17%, according to a Times analysis of census data. The Latino population grew from about 18% to 51% over that time period.

The new, nonwhite residents often were blamed for crime and gang problems, with Section 8 housing becoming a touchstone for racial animosity.

In 2010, a sheriff’s deputy posted a photo on a Facebook page called “I Hate Section 8” of luxury cars in the Palmdale garage of a Section 8 voucher recipient. He had taken the picture while conducting an official compliance check. Soon, the home was vandalized with racist graffiti. Someone threw urine at the tenant’s son while yelling a racial epithet. The family eventually left town.

In 2013, a judge ruled that Palmdale’s at-large voting system violated state law and hampered the ability of Black people and Latinos to win office. The city fought the ruling but agreed in 2015 to vote by geographic districts.

The Antelope Valley Union High School District was roiled by allegations of racism last year, and four Palmdale elementary school teachers were placed on leave after a photo of them smiling and holding a noose circulated on social media.

In Palmdale and Lancaster this week, Black residents said they often don’t feel welcome.

Elaijaha Braddock, 25, who is Black and moved to Palmdale with her mother four years ago, said authorities’ initial response to Fuller’s death matched the area’s reputation for racial animosity.

“I used to come here to do college work,” Braddock said, pointing to the city library, near the site of Fuller’s death. “I don’t feel safe here. It all makes me feel hopeless and scared for my little 5-year-old-brother.”

Domonique Boyd, 26, said that when he was growing up in Palmdale, students often called him racial epithets. Once, a man threw a bottle of Gatorade and cursed at him and his Black friends as they walked down the street.

Three years ago, Boyd was returning from a dance competition in L.A. at about 1 a.m. and pulled onto Palmdale Boulevard. He was stopped by police, allegedly for failing to yield to traffic. But Boyd saw no other cars.

Boyd said a deputy asked his light-skinned friend to step out of the vehicle but dragged Boyd out and slammed him into the hood of his car.

“I’m a grown man, and I can’t even get out of my own car. I’m dragged out,” Boyd said. “When I see them, I don’t feel safe.”

Johnathon Ervin of Lancaster attended a vigil for Fuller last week with a heavy heart. Ervin, who is Black, had already spent weeks talking with his children about the death of Floyd. He worried about his oldest son, who is 18.

“He doesn’t have the leeway to make one mistake, because it could mean death. And that is scary,” said Ervin, 41. “I don’t know if people understand how many families have been up at night thinking about their kids and the safety of the country that we live in and how we can’t protect them out on the street.”

When Ervin, an aerospace engineer and Air Force Reserve senior master sergeant, ran for a seat on the Lancaster City Council in 2014, Lancaster Mayor R. Rex Parris, who is white, sent out a campaign mailer that labeled Ervin a “gang candidate.”

That same year, Ervin had been stopped on the street by sheriff’s deputies who said he resembled someone cited in a warrant. It was deeply unnerving.

“I said, ‘I’m Johnathon Ervin. I’m running for office. Here’s one of my cards. I don’t have any warrants,’” he said. “It was jarring.”

Times staff writer Doug Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.