One-way halls, lunch at desk, playing alone. L.A. schools could reopen with stark rules

- Share via

Sixteen students to a class. One-way hallways. Students lunch at their desks. Children could get one ball to play with — alone. Masks are required. A staggered school day brings on new schedules to juggle.

These campus scenarios could play out based on new Los Angeles County school reopening guidelines released Wednesday. This planning document will affect 2 million students and their families as educators undertake a challenge forced on them by the coronavirus crisis: fundamentally redesigning the traditional school day.

The safe reopening of schools in California and throughout the nation compels the reimagining — or abandoning — of long-held traditions and goals of the American school day, where play time, socialization and hands-on support have long been essential to the learning equation in everything from science labs and team sports to recess and group work.

The Los Angeles County Office of Education guidelines offer an early top-to-bottom glimpse at the massive and costly changes that will be required to reboot campuses serving students from preschool through 12th grade, critical to reopening California. The 45-page framework was developed through the work of county staffers, outside advisors and representatives from 23 county school systems, each of which must develop its own reopening plan.

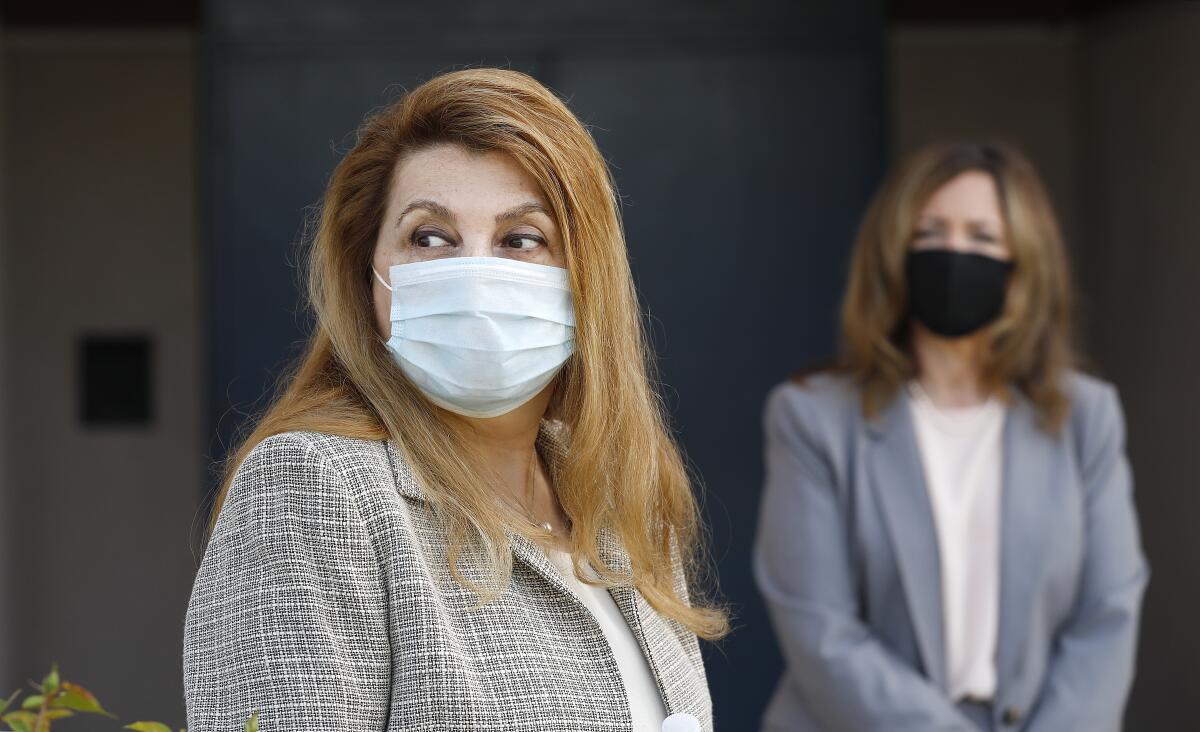

“Our main priority is health and safety,” said Debra Duardo, the superintendent for the L.A. County Office of Education, which provides services and financial oversight for the county’s 80 school systems. “Unfortunately some of the things that children could enjoy in the past, they’re not going to be able to do that.”

The county’s guidance came out before the state Department of Education released its own framework for California’s 6.2 million public school students. State Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond said Wednesday to expect that “guidebook” in early June.

“We expect ... that students and staff should be wearing a face covering at school,” Thurmond said. Schools should follow the lead of childcare centers open now, which take temperatures when children enter and ask parents to take their children’s temperatures before they leave home. “We’re going to have to use every part of the campus to make sure that we have six feet of distance,” whether in the classroom, at lunch, or on the way to and from campus.

When campuses closed in mid-March, school systems scrambled to develop a new style of education on the fly — one that relied on “distance learning.” Administrators quickly handed out computers and internet hot spots. Teachers trained on Zoom and other online platforms. Parents oversaw learning at home, even as they faced economic hardship.

Despite these Herculean efforts, school leaders and teachers report uneven student engagement and impediments to learning at home, underscoring the importance of an academically robust return to campus — even as the governor’s proposed budget envisions a cut for schools of about 10%.

A walk-through Tuesday at Cerritos Elementary School in Glendale put the complexities into focus.

The campus has the natural advantage of multiple outdoor spaces: The doors for the youngest students’ classrooms open directly onto a circular courtyard leading to a student garden — no need for these students to go through hallways to get to class.

The guidelines recommend making use of outdoor spaces — where the threat of virus transmission is lower.

But how exactly do you keep kindergartners and other youngsters six feet apart?

“That is a big challenge because our nature is to play together and the socialization is so important at that age,” said Cerritos Principal Perla Chavez-Fritz. “Maybe hula hoops and things that the students can play together alone.”

Then there’s the challenge of requiring students, especially little ones, to wear masks all day — if they’re fiddling or taking them on and off, the sanitation benefit declines. Some students with disabilities or health issues cannot safely wear masks.

The other side of Cerritos Elementary opens onto a grassy field adjacent to a covered eating area — additional helpful outdoor space. But the massive, brightly hued play structure is likely to be off-limits.

Under the guidelines, the spacious eating area could be used for some classroom activities, but not for the traditional lunch period gathering. It’s safer for students to remain in class, eating at their desks, spaced six feet apart.

The county said school districts could consider hybrid learning models, with students spending half the school day at home to reduce class size, and perhaps eliminating lunch period altogether — by sending students home with a bagged meal.

A hybrid model would likely require some element of distance learning, which many children statewide are still not equipped for, Thurmond said Wednesday. About 600,000 California students are still waiting for a computing device and 300,000-400,000 need internet hot spots, a gap that would cost at least $500 million to fill.

Enter second-grade teacher Emily Miranda’s classroom and other issues become obvious. Her classroom opens onto an interior hall — which new guidelines suggest be turned into a one-way passage to limit jostling.

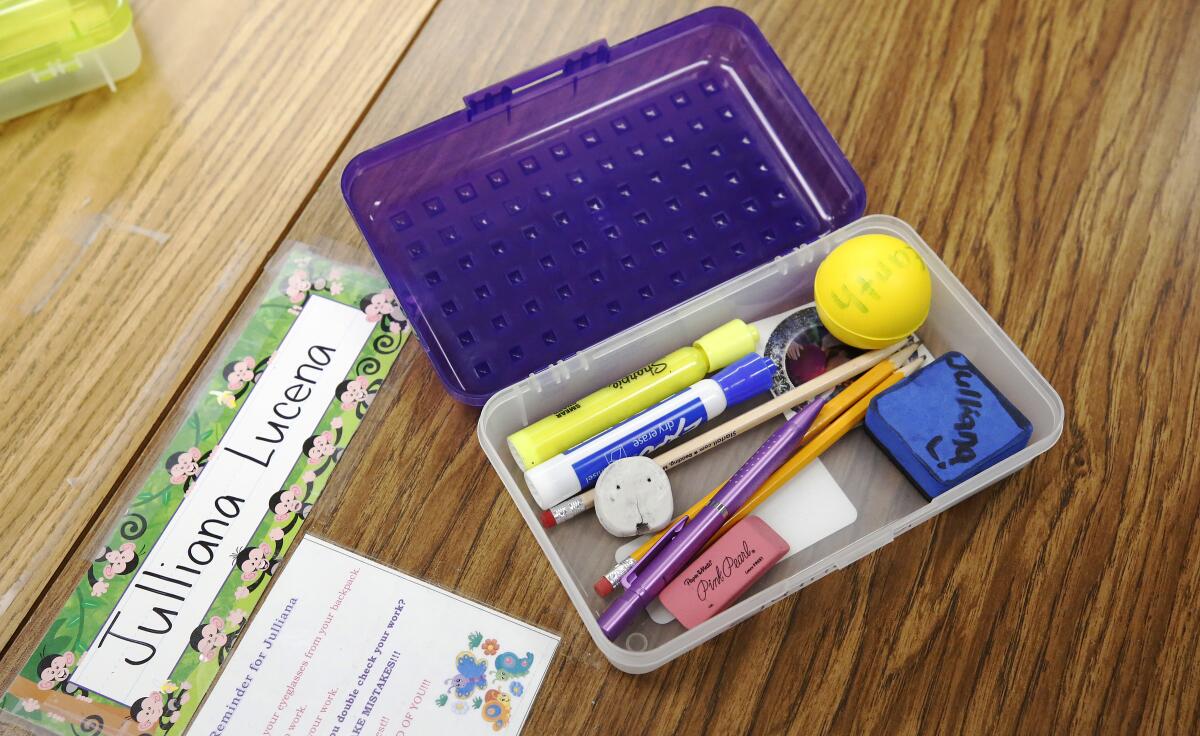

Inside, the room is frozen in mid-March, walls festooned with student work for display at an open house that never happened: book reports on Dr. Seuss; crayon and collage pieces for the Fine Arts Day display. Book orders were due March 13. A girl’s pencil box is open and askew.

Student name tags show that Ryan, Lucas, Addison and Maya sat facing one another with their desks pushed together. That wouldn’t work for the fall. The guidelines suggest facing all desks the same way, six feet apart.

Plus, there are too many desks — far more than the 16 the guidelines recommend in a standard-sized California classroom. And there’s just too much furniture, including a student activity center at a kidney-shaped table. That’s too much to keep clean, to disinfect and to allow for physical distancing.

The guidelines suggest that administrators rent storage pods for unusable furniture.

“We’ve measured,” said Vivian Ekchian, the superintendent of Glendale Unified School District. “We’re going through all the different scenarios to see how many tables, how many chairs, how many desks, how many students would have to be in a classroom for us to remain safe and make sure that instruction still occurs.”

At Cerritos Elementary, all classrooms have sinks, but that’s not true everywhere. The guidelines recommend building time into the schedule for frequent hand washing.

The carpet on Miranda’s floor — where students recently huddled during storytime to listen to her read such books as “Horrible Harry,” “The Frog Prince,” “The Mangrove Tree” — may also have to go because it’s too small for social distancing. And those books — part of Miranda’s huge classroom library — are impossible to sanitize daily, and may have to be packed away.

Students may have to read online, Ekchian said, adding, “We will be purchasing for our students their own personal equipment. So whether it’s their masks or crayons and pencils, whatever is appropriate at that age level. And it might include a basketball which they can use. It might not be in a team sport.”

Ekchian can’t imagine having to reduce staff because of proposed budget cuts. She’s thinking that necessary new hires might include bathroom attendants, to keep those areas properly supervised.

So many unknowns remain, said Alejandro Ruvalcaba, superintendent of the Rosemead School District, south of Pasadena.

If the county is in Phase 5 of reopening, school will be closest to normal, he said. Although the district also must be ready, for example, to handle more restrictive openings and split schedules.

“We don’t know whether it’s going to be every other day,” Ruvalcaba said. “We don’t know whether it’s going to be AM/PM, and it might be a combination of both.”

And one instructional plan won’t be enough, said Lancaster School District Supt. Michele Bowers, who served on the task force along with Ekchian and Ruvalcaba.

“Not everyone wants their child to be in a school setting,” said Bowers. “Some need a school setting for various reasons. Some are very comfortable with a blended model.”

The uncertain timeline of restructured schools is worrisome, said UCLA education professor Pedro Noguera.

Schools offer an important environment where children learn to socialize with one another, he said.

The diminishing of play, lunch table chatter and personal contact could hurt students if such measures continue in the long term.

“There are a lot of kids that are more social, and they look to school for their friends and their teachers.” Noguera said, “and they’re going to be at a huge disadvantage.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.