As California beaches reopen, seawall construction becomes legislative battleground

- Share via

California’s beaches may feel off-limits right now, but the coronavirus has not stopped the sea from rising. With every tide and storm, this slow-moving disaster continues to creep closer to shore — toppling bluffs, eroding our beaches and threatening homes and major infrastructure.

Also on the rise is a heated battle over what gets saved — and who actually benefits — along the California coast.

In a move this month that outraged environmentalists and caught coastal regulators off guard, a Republican senator pushed forward legislation that would revise a key section in the state’s landmark Coastal Act and allow homeowners in San Diego and Orange counties to build seawalls by right. These changes would set a precedent of sidestepping the required (and often tough) oversight of the California Coastal Commission, which for decades has walked the contentious line between protecting private property and preserving the very beaches that make California, well, California.

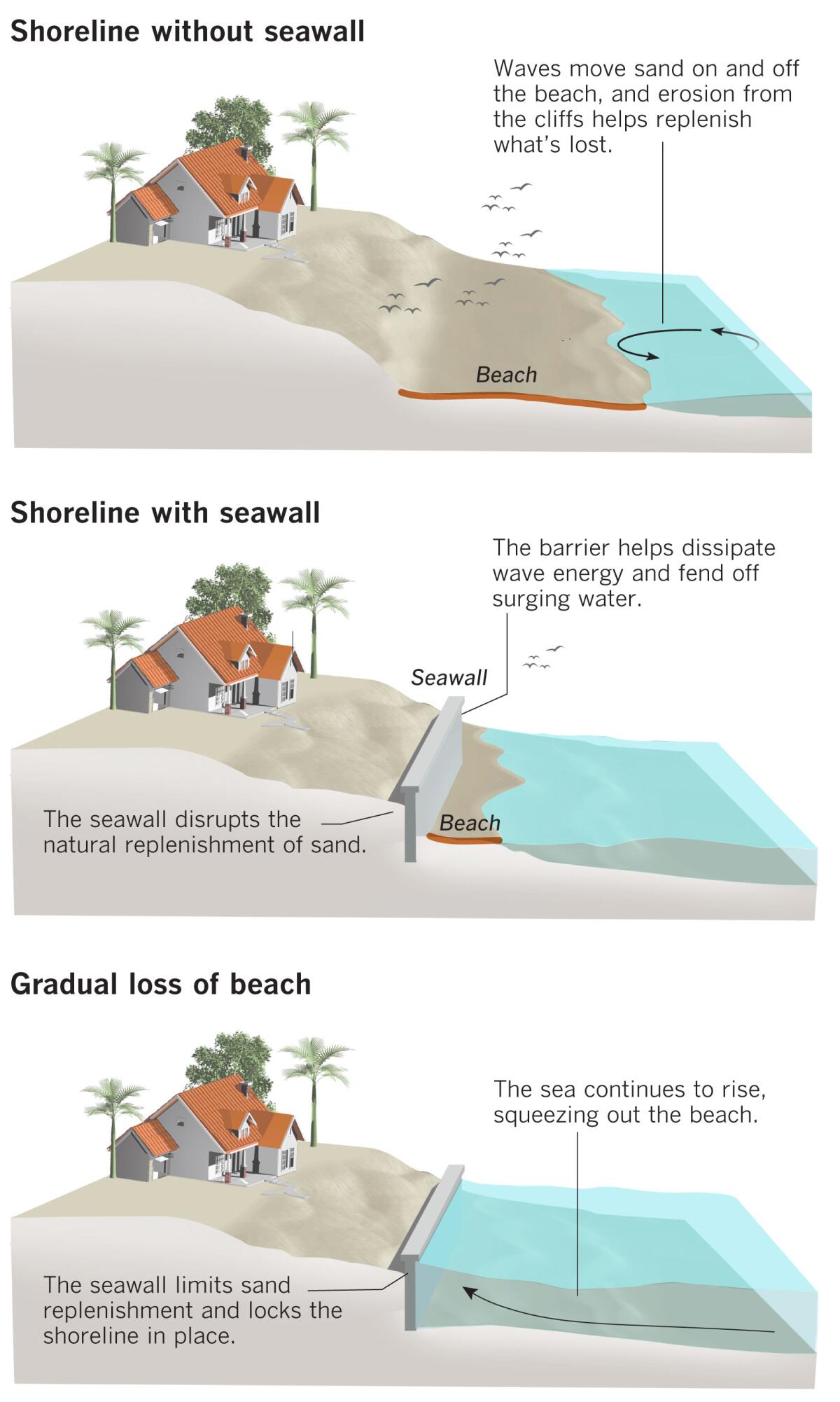

Seawalls, while effective in protecting beachfront homes and infrastructure in the short term, are controversial because they disrupt the erosion and natural replenishment of sand — stripping away beaches until they narrow or vanish altogether. For every new seawall protecting a home or road, a beach for the people is sacrificed.

Homeowners fighting sea level rise say going to the Coastal Commission for any form of protection has increasingly become a non-starter. This new legislation, supporters say, would streamline a frustrating permitting process that could ultimately save lives. They point to the bluff collapse in Encinitas last summer that killed three women.

“Make Southern California’s Coastal Bluffs & Beaches Safe Again,” supporters of the bill, SB 1090, declared. “The California Coastal Commission is failing us.”

Opponents call the bill a thinly veiled attempt by the author, Sen. Patricia Bates (R-Laguna Niguel), to allow wealthy coastal enclaves to finally get away with armoring their own properties without considering the broader consequences. If public safety was truly the concern, there would be a number of other options on the table — such as moving the structures themselves out of harm’s way, they said. Only an unimaginably massive seawall, one that no homeowner would ever propose, could prevent a total cliff collapse like the one in Encinitas.

“It’s an outrageous and reckless proposal that would destroy Orange County’s public beaches for private benefit,” said Denise Erkeneff, who has lived in Dana Point for 25 years and coordinates the Surfrider Foundation’s South Orange County chapter. “Efforts to protect public access to the coast will be for nothing if there is no coast or beaches left to visit.”

The stakes are high as this controversial legislation makes its way Tuesday to a senate committee. Many have noted in recent weeks how the emotional reactions to COVID-19 beach closures make it clear just how devastating it would be if California permanently lost its beaches.

As Bates and her supporters worked on SB 1090 during the pandemic, other officials across the state have been holding virtual workshops and joining forces to confront the social, economic and environmental catastrophe of sea level rise. More than a dozen key agencies recently agreed, in a set of targets guided by Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration, to prepare California for at least 3.5 feet of sea level rise by 2050.

Homes are already flooding, and critical roads and infrastructure are already mere feet from toppling into the sea, they said. In Southern California alone, two-thirds of beaches could vanish, and seaside cliffs could erode 130 feet farther inland. Legislative analysts, in an unprecedented report, made the case that any action — or lack of action — within the next 10 years could determine the fate of the California coast.

But what exactly this action looks like — and who pays and who benefits — remains a tough balancing act as California moves toward a more cohesive approach to sea level rise. Across a state whose coastline spans 1,200 miles, every community faces slightly different challenges and often fights for its own priorities.

In Orange and San Diego counties, where train tracks run precariously close to the edge of collapsing cliffs in Del Mar and storms last winter eroded Capistrano Beach so much that a boardwalk collapsed, Bates said she hears of her constituents getting stymied by the permitting process. She wonders if the enforcement of the Coastal Act has become too closed-minded in the face of sea level rise.

Charlie McDermott, who lives in Encinitas and has watched this stretch of coast erode for the past 26 years, said the bluff collapse last summer still haunts him. He and his daughter watched first responders frantically digging through the rubble, trying to save three women who ultimately lost their lives. This tragedy followed similar preventable deaths in past years, he said, and he has been frustrated that “the current coastal management strategy does not prioritize erosion mitigation.”

“Instead it is deliberately enabling bluff slides, failures, erosion and collapses that will continue to kill people on our beaches and block public access,” said McDermott, who said he values beaches and respects the intent of the Coastal Act, but couldn’t help but feel that the commission now seems to be creating “hazards with the hope of condemning public and private structures in order to ‘re-wild the coast’ in urban areas.”

SB 1090 seeks to reestablish a balance and trust that residents feel no longer exists, said Bates, who visited McDermott’s home last year and has been working with him and others on the details of the legislation. “It’s something that we need to start talking about, and I thought this was a good way to start.”

The bill would require coastal officials to approve permits for construction, repair and maintenance of erosion protective devices in all beach areas in the two counties — unless a finding is made that the project would be a substantial threat to health or safety.

The applicant would also be required, Bates noted, to pay a fee of $25,000 or 1% of the assessed value of the private property, whichever is less, to help replenish sand to the beach.

The Coastal Commission was appalled last week when they heard about these provisions and questioned their true intent, before voting unanimously to oppose the legislation. The bill would grant special privileges to oceanfront owners, they said, and set an adverse precedent for other communities grappling with their own erosion problems.

“This bill would essentially allow any property owner in Orange or San Diego counties to construct a seawall regardless of the impacts to habitat, access, public recreation, scenic viewsheds or impacts to neighboring properties — so long as it meets current building codes and they could afford it,” Sarah Christie, the agency’s legislative director, reported to commissioners. “With no ability to hear these projects on appeal, the bill essentially exempts seawalls from the Coastal Act.”

More than 30% of the Orange County and San Diego coast is already behind some form of seawall. And the beach mitigation fee is “woefully insufficient,” Christie said, when compared to how much it actually costs to truck sand in to rebuild a vanishing beach.

“While it is completely understandable that property owners want to build seawalls to protect their properties, this bill doesn’t take into account all that we’ve learned about the inevitable consequences of coastal armoring,” she said. This approach to sea level rise would “exacerbate the already accelerated loss of public beach space in Southern California due to coastal erosion and inundation.”

Mark Gold, the governor’s deputy secretary for coast and ocean policy, did not comment on the bill but said that it was important for California to work together on balanced and equitable solutions. Momentum across the state has been moving toward one of coordination and collaboration, he said, and making sure everyone remains on the same page is absolutely necessary when confronting everything that’s at stake.

“The beaches that all of us grew up on and love so much — many of those are in jeopardy if we don’t do anything to protect our coast,” he said. “Climate change isn’t taking a holiday and is still posing major problems globally and right here in California.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.