How a reclusive ‘town of aging hippies’ worked to screen itself from coronavirus

- Share via

BOLINAS, Calif. — When the coronavirus outbreak appeared likely to rage through the Bay Area weeks ago, residents of this hermit-like beach community tried to protect themselves by doing what they do best — keeping out strangers.

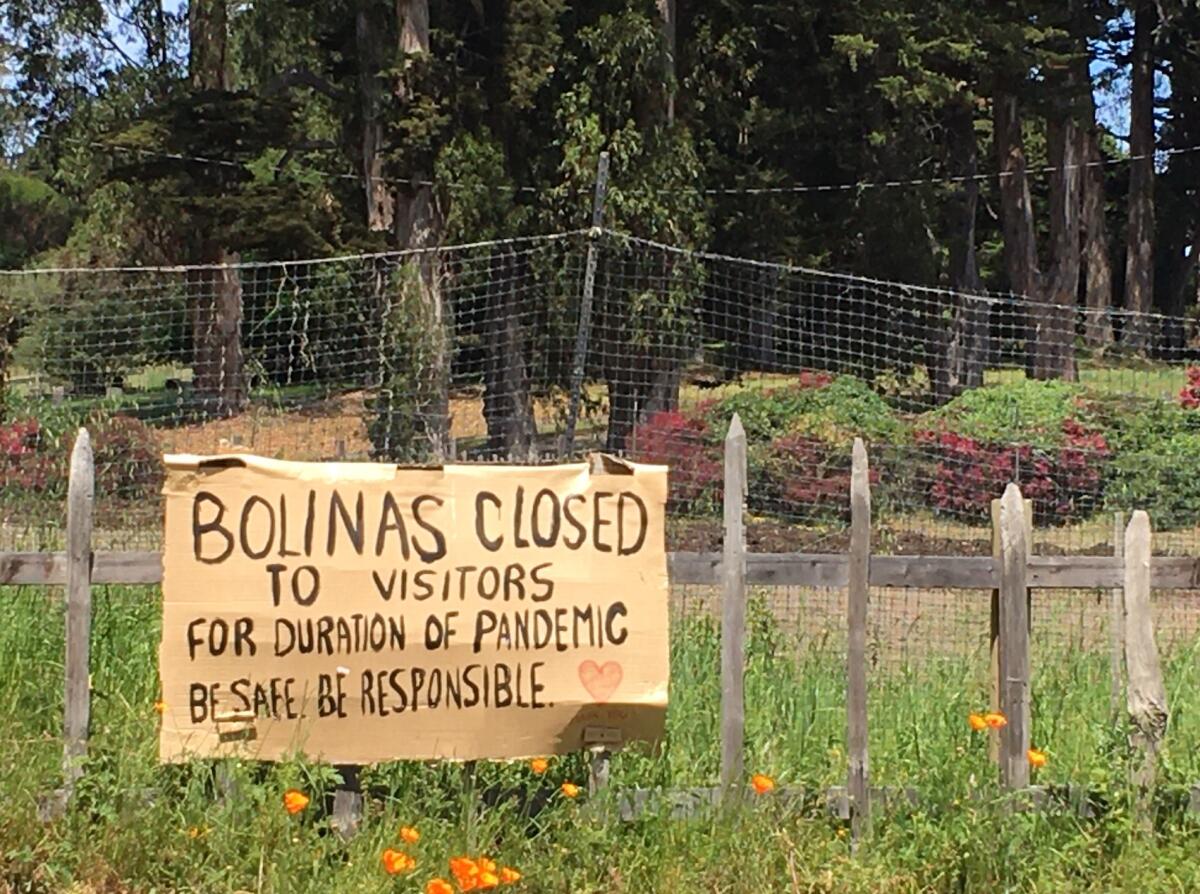

Despite a regional stay-home order, outsiders were inundating Bolinas, which sits just south of Point Reyes National Seashore in west Marin County. Yelling matches ensued. Residents posted themselves at the entrance to town and shouted at drivers, “Go home!”

Under a homemade “Bernie 2020” sign painted in red, residents hung two others: “Bolinas closed to visitors for duration of pandemic. Residents, deliveries only.”

Jyri Engestrom, 42, a venture capitalist who owns a home here, worried that the pandemic would rage through town, which has about 1,600 residents, many of them seniors. Some residents had symptoms but could not get tested.

“I was getting scared because frankly this is a town of aging hippies whose idea of social distancing is not to hug each other as much,” he said.

Working with volunteer and nonprofit groups, Engestrom organized a testing project for all willing residents, Bolinas employees and front-line workers. On Friday, UC San Francisco, which processed the samples, announced the results of 1,845 nasal and oral swab tests. No one was infected.

Surrounded by the sea on three sides and reachable from San Francisco by a long, windy, cliff-edged, two-lane road, this hamlet is best known for its disdain of development and outsiders. Bolinas leaders limited water hookups decades ago to keep the community small and tore down traffic signs that pointed the way to town.

Still, high-tech entrepreneurs managed to purchase homes, and property values and rents skyrocketed. The entrepreneurs ingratiated themselves, donating money for local causes, including a park. Residents said they have also helped pay for free meals and masks during the pandemic. The town has come to appreciate the beneficence.

“They don’t understand the town,” said Bolinas resident Rudy, 69, chatting with another man on a street overlooking a lagoon. “But they are exceedingly generous.”

Rudy declined to give his last name. “Bolinas is a secretive place, you know,” he said.

A city sign in front of a trail leading to the water reads: “All non-residents may be subject to fines. Shelter at home.”

Engestrom said the mass testing a week ago proved surprisingly easy. Even though hospitals were short of the components needed for tests, the organizers improvised and used what was plentiful. They are planning to publish a blueprint for other communities that want to follow their example.

He and Cyrus Harmon, 49, who founded a pharmaceutical startup and moved to Bolinas 10 years ago, got the idea for community-wide testing after reading about the northern Italian town of Vo. It tested nearly all its 3,000 residents at the height of the coronavirus outbreak. The two men said they wanted to give something back to the town.

Mark Pincus, who founded online game maker Zynga and also owns a home in Bolinas, donated the first $100,000.

Volunteers flocked to help. “It is not about tech executives doing this,” Harmon said. “It is about the community coming together and doing it.”

Engestrom knows the optics of rich people being tested while poor people go without are disturbing, but he said most residents in Bolinas live modestly.

The median household income is about $58,000 and the median age is 62.5. More than 16% of the residents, mostly 65 and older, live below the poverty line, according to census data.

“I am definitely an outsider because I am part of the problem,” said Engestrom, who bought a home here in 2014 . “We are jacking up the housing prices by coming here from San Francisco. I feel that.”

He and other organizers of the testing project, working with infectious disease experts at UC San Francisco, had to scavenge for supplies. The long swabs typically used for testing were unavailable, but shorter swabs that experts said would suffice were plentiful.

For protective gear for testers, the organizers scoured hardware stores for painter suits, also approved by scientists. A call on social media for the face shields produced so many that Engestrom has a storage-room full that he can’t give away. Volunteers went online to hire phlebotomists — certified testers — to take the samples, obtained gloves from restaurant suppliers and masks from friends who bought them from China.

A volunteer team of Airbnb engineers built the platform residents used to schedule appointments for the tests, and a GoFundMe page brought in donations, most under $1,000. Eventually, about $360,000 was raised. The biggest payment went to UCSF, which subsidized the project.

In addition to sampling residents for the virus, the town also tested them for antibodies. UCSF has started a companion study to test residents of San Francisco’s highly dense Mission District, where infections have spread.

The Bolinas organizers purchased wedding tents for the testing and set them up in the parking lot of a town park. Tests were done over four days.

Among the few who declined was Bruce Dark, 67. He has lived in Bolinas for 32 years.

“It is mass hysteria,” he said. “I have talked to 15 people, and no one knows anyone who has died.”

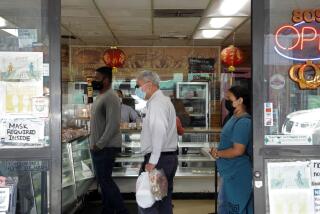

Dark was huddled with two other men in the city’s tiny downtown, which includes gas pumps where regular grade last week was selling for $5.99 a gallon, a bar, a grocery store, a surf shop, a cafe and a hardware store. The main street dead ends at the beach.

One of Dark’s friends declined to be interviewed. “Go back to Los Angeles,” he shouted.

Dark, though, was congenial. He wore a blue head covering and a print cloth mask, which he regularly lowered and raised. As he inched closer to a masked reporter to better hear, he said, “Don’t worry. You won’t get sick.”

During the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, some communities walled themselves off from others and managed to escape the disease, said Dr. Robert Benjamin, a longtime Bay Area public health officer. He questioned whether that was possible today.

The value of the Bolinas testing was “purely surveillance information,” he said, and could be used to determine when places should reopen.

The latest maps and charts on the spread of COVID-19 in California.

“It is a snapshot,” he said. “It says nothing about tomorrow.” As long as the town didn’t use testing supplies that were more urgently needed by others, he saw no problem with it.

Engestrom said he knows the town “dodged a bullet this time.” The mood now is one of relief.

Engestrom, a native of Finland, said he fell in love with Bolinas years ago. He said it reminds him of a small Italian or Spanish town where elders take the time to meet and chat on the streets.

The residents’ animosity toward outsiders might seem “obnoxious,” he said, but the old timers “are defending their right to exist without having the means to do so anymore.”

“I feel like they are fighting a losing battle,” he said. “The power of capital is just so overwhelming.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.