- Share via

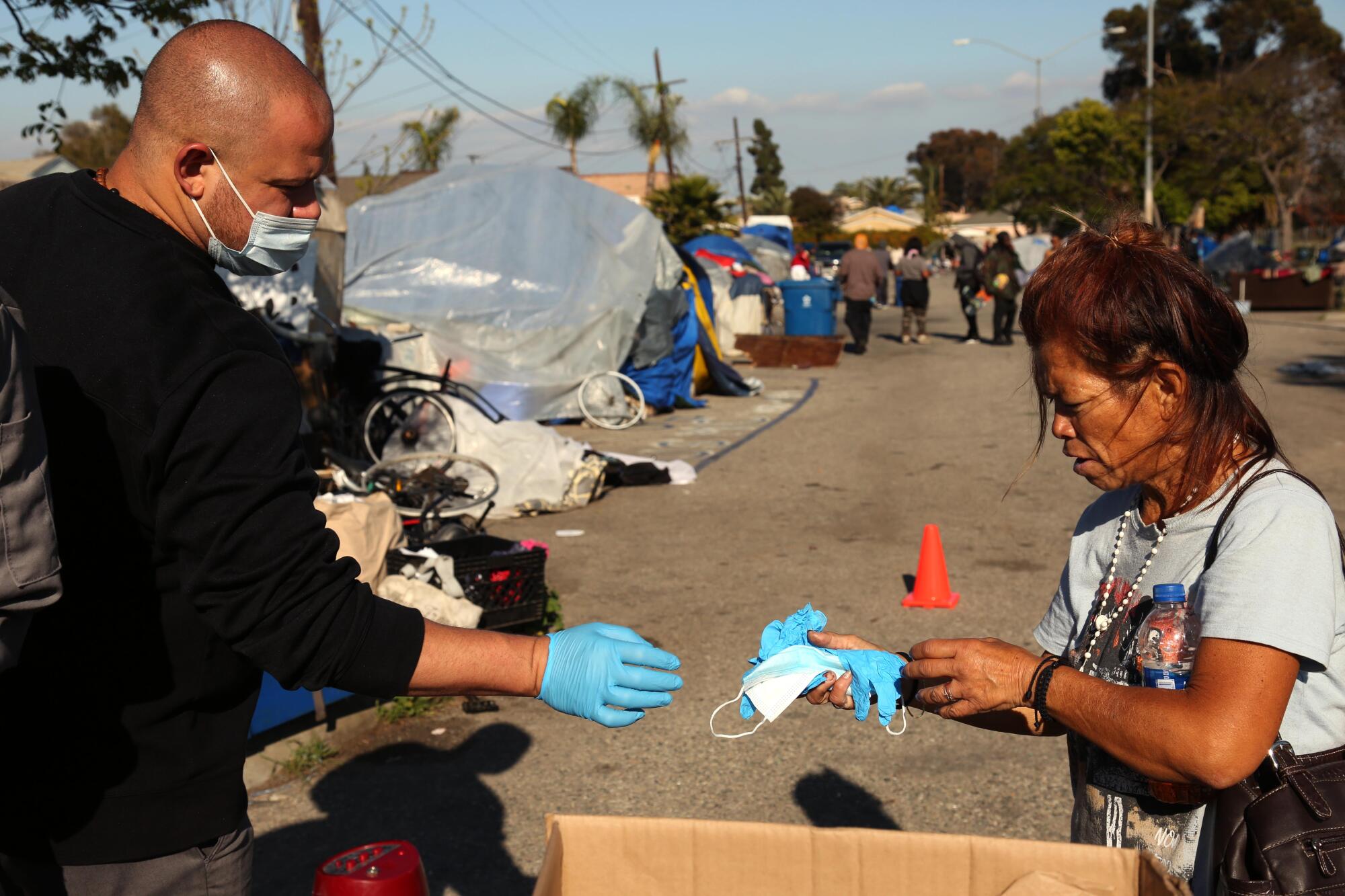

Gernay Quinnie Jr. slipped on a mask and gloves on a recent morning and set out to quell tensions in his West Athens neighborhood.

He talked a young man through a conflict with his mom. He helped a group of young people make food boxes for neighbors. He then drove to a nearby homeless encampment to pass out food and toiletries and explain how to properly use a mask and gloves.

The tasks all carry an added threat of contracting the coronavirus, and Quinnie, who has an immune disorder, is especially at risk.

With much of Los Angeles County shuttered because of the pandemic, Quinnie is one of many gang intervention workers still on the streets, tending to the neighborhoods where they grew up, places where historical disparities in access to healthcare, jobs and adequate housing make residents especially vulnerable to infection and death.

“If I don’t go out, who else is going to do it,” said, Quinnie, 38, who has worked with Reclaiming America’s Communities Through Empowerment, an intervention and prevention group, for about a year.

The intervention workers — some themselves former gang members — help reduce violence and retaliation and broker peace between rival street gangs. Los Angeles County is one of a handful of places that has designated such work as essential during the coronavirus pandemic.

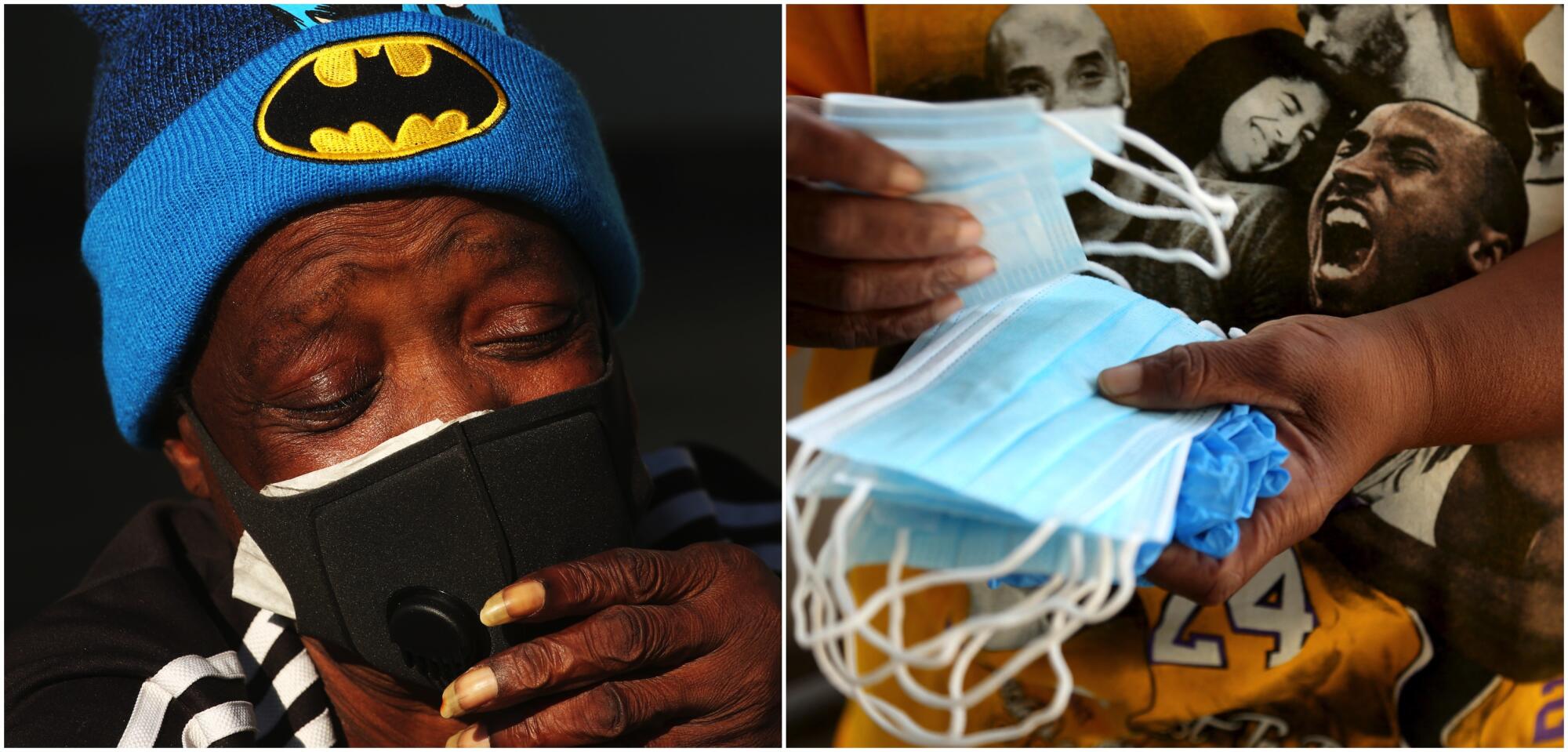

These days, the workers also are using their street credibility to dispel misinformation and educate people about the coronavirus. They’re trying to adapt to the needs of their communities, whether it’s walking door-to-door to feed the newly unemployed and the homeless or setting up Zoom meetings for young people to ask questions about the virus.

And they’re trying to defuse tensions that arise among cooped-up family members and stir-crazy youths.

“These are not just those guys who know how to negotiate peace treaties; they are a community asset,” said Jorja Leap, a gang expert at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs. “Historically and presently, where authorities are not trusted, these men and women ... are the go-between, the objects of trust.”

Their roles as sounding boards have become more vital as the daily onslaught of news alarms or traumatizes some, said Ben “Taco” Owens, who supervises a team of 11 intervention workers.

“You don’t know if it’s the end of the world or what’s going on,” he said.

Since the outbreak, Kevin “Twin” Orange has been unofficially patrolling a 7-Eleven near West Century Boulevard and South Vermont Avenue down the street from his home. He also drives by the marijuana dispensaries in his neighborhood to break up parking lot fights. He encounters people who don’t understand the concept of social distancing, so he tries to educate them about maintaining space and taking other precautions.

Recently, an episode in South Los Angeles where police broke up a backyard birthday party of about 40 to 50 people turned volatile, with angry residents yelling profanities.

The party, for a 1-year-old, violated the city’s safer-at-home order, which now bans public and private gatherings.

The next day, Orange met with other intervention workers from across the city to try to get the word out about why gathering in groups could be dangerous.

He’s told more than one teenager that this virus isn’t just about them. “Let’s think about who is in your household,” he will say.

Orange is also thinking about his own home, where he lives with a relative who has an underlying health condition. He bathes and changes his clothes as soon as he arrives.

“I’m mindful of that threat that’s always out there,” he said.

Los Angeles City Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson, whose district encompasses a chunk of South L.A., said the area had seen a spate of shootings in recent weeks. Although violent crime is down in the city, intervention workers are still on the streets, talking to young men to prevent retaliatory shootings.

In addition, workers in his district have volunteered to deliver meals to seniors, which helps them keep tabs on the community.

“These men and women did not miss a beat,” he said. “They didn’t wait around for anybody to tell them what they ought to be doing or should be doing. “

Skipp Townsend, executive director of the gang intervention nonprofit Second Call, said social media taunts played a role in at least one of the recent shootings. Some people still gather at events that can turn volatile, he said, adding that two people were shot at a party a few weekends ago.

“The younger people are still consistently antagonizing each other on social media,” he said.

Other gang intervention organizations have stepped up education efforts. Tina Padilla, a program manager at Breaking Through Barriers to Success in northeast Los Angeles, held a Zoom call recently for young clients seeking guidance about the novel coronavirus.

Some in the community still want to hug or shake hands. Others think the government is using COVID-19 to control Americans. Some believe the coronavirus can be cured with a shot of tequila.

“COVID-19 is something they can’t see,” Padilla said. “They’re already living a risky lifestyle, so how is something they can’t see going to get them?”

After shootings, intervention workers typically go to hospitals to connect families with services. Now, with hospital visits discouraged, Padilla said there’s a lag in providing resources.

Instead, case workers are assigning young people writing projects, playing online trivia and giving out board and card games to “try to keep their minds busy.”

“I do know they’re getting stir-crazy,” she said.

Gerald “Pee” Cavitt, executive director of Chapter Two in South Los Angeles, said people were coming by his office off East Florence Avenue to ask questions about the coronavirus. He’s also organized several food giveaways in the neighborhoods he works in.

“People are fearful,” Cavitt said. “We thought they didn’t have money then; they don’t have money now.”

He’s educated a number of gang members about the virus and safety measures so they can take the information back to family and friends.

“These are the people who can really make a difference,” he said.

On a recent rainy afternoon, Claudia Bracho, program director for the HELPER Foundation, donned a mask and gloves and stood in a Venice apartment courtyard. Since the crisis began, Bracho and a team of intervention workers — Clinton Noble, Ebay Williams, Melvyn Hayward III and Ansar Muhammad — have been distributing donated groceries to low-income families and senior citizens in the Venice and Mar Vista area.

“We got bread and produce! We got bread and produce!” Bracho shouted. The group trudged through the rain for hours, slipping bags with fresh asparagus and broccoli through iron gates.

In recent weeks, they’ve picked up prescriptions for people and run errands. They’ve found ways to connect young people to one another, such as by eating breakfast as a group on Instagram Live.

Bracho’s organization serves mostly Latino and black families, some of whom are distrustful of authorities. They’ve provided Spanish translations of physical distancing guidelines.

“Since we’ve helped them with a lot of things, our word carries weight,” she said.

For Cassandra Bibbs, a lifelong Venice resident with a heart condition, the gestures are a lifeline. Bibbs says her 12-year-old grandson, whom she is raising, has asthma.

“He has to stay in the house,” she said. “That’s the choice I made to keep us safe.”

Since the stay-at-home mandates were issued, people from Bracho’s organization have come by several times each week to deliver sack lunches and groceries. Some of the intervention workers helped her grandson with his homework on FaceTime.

“It’s a big help,” Bibbs said.

Around the corner, Geo Martinez shares an apartment with his mother and brother. He was recently furloughed from his job at a local restaurant and said that as the days went by he worried more and more about money.

On a recent afternoon, Martinez was sitting in his apartment, looking out the window, when he heard Bracho’s voice. She had bags of groceries.

“I was thinking, for real?” he said. The food brought Martinez a brief respite. Then, two days later, the group was back with more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.