Southern California outpacing Bay Area in new coronavirus cases. So where’s the peak?

- Share via

The San Francisco Bay Area suffered one of the nation’s earliest outbreaks of COVID-19, but cases from Southern California and the Central Valley are outpacing it, threatening a much larger population, according to a Times analysis of county health data.

Los Angeles, San Diego, Riverside, San Bernardino, Kern, Stanislaus and Tulare counties are now seeing faster rates of newly detected coronavirus cases than any of the counties in the Bay Area, the Times analysis found.

And with more than 6,000 confirmed cases in L.A. County alone, chances of exposure are increasing rapidly.

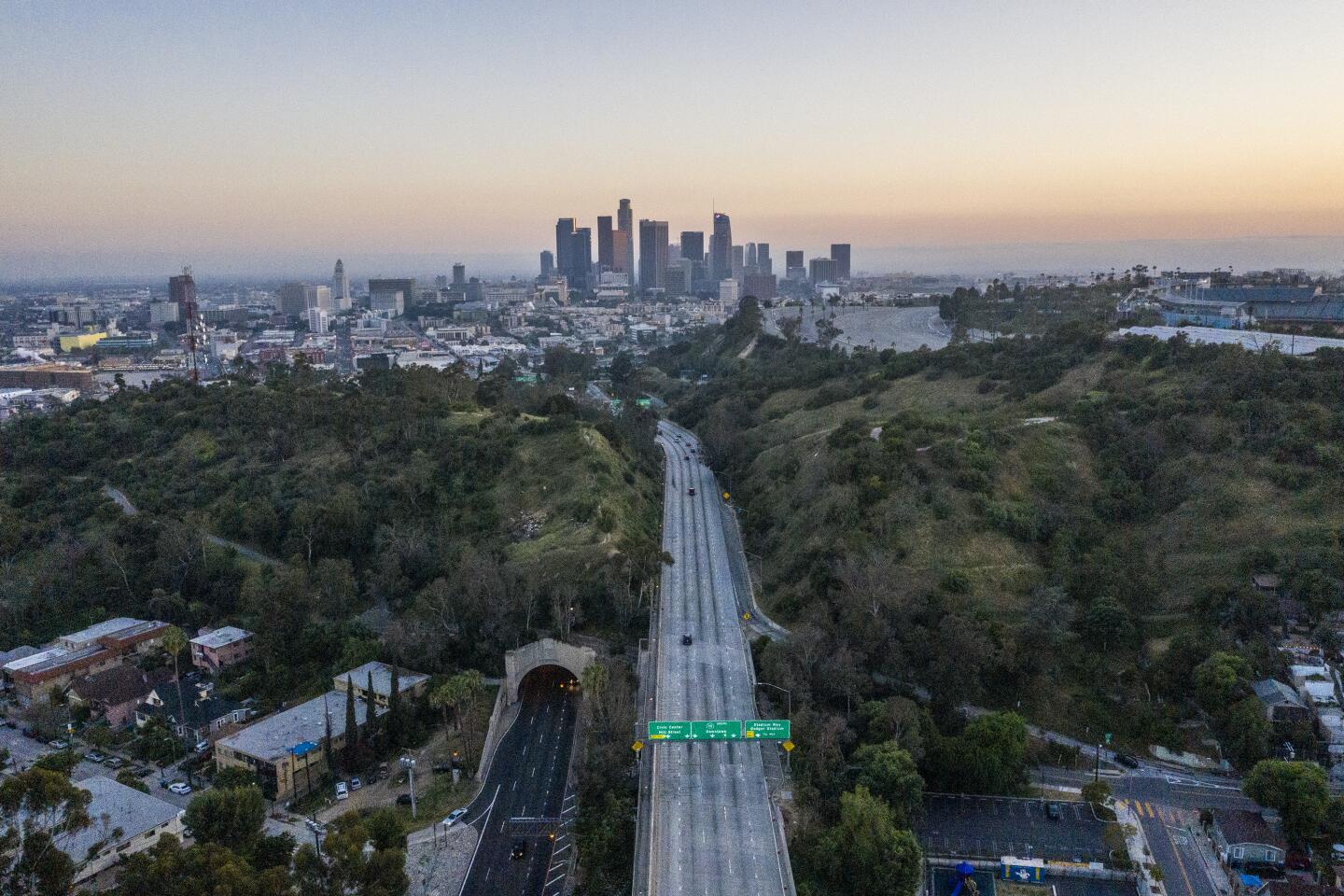

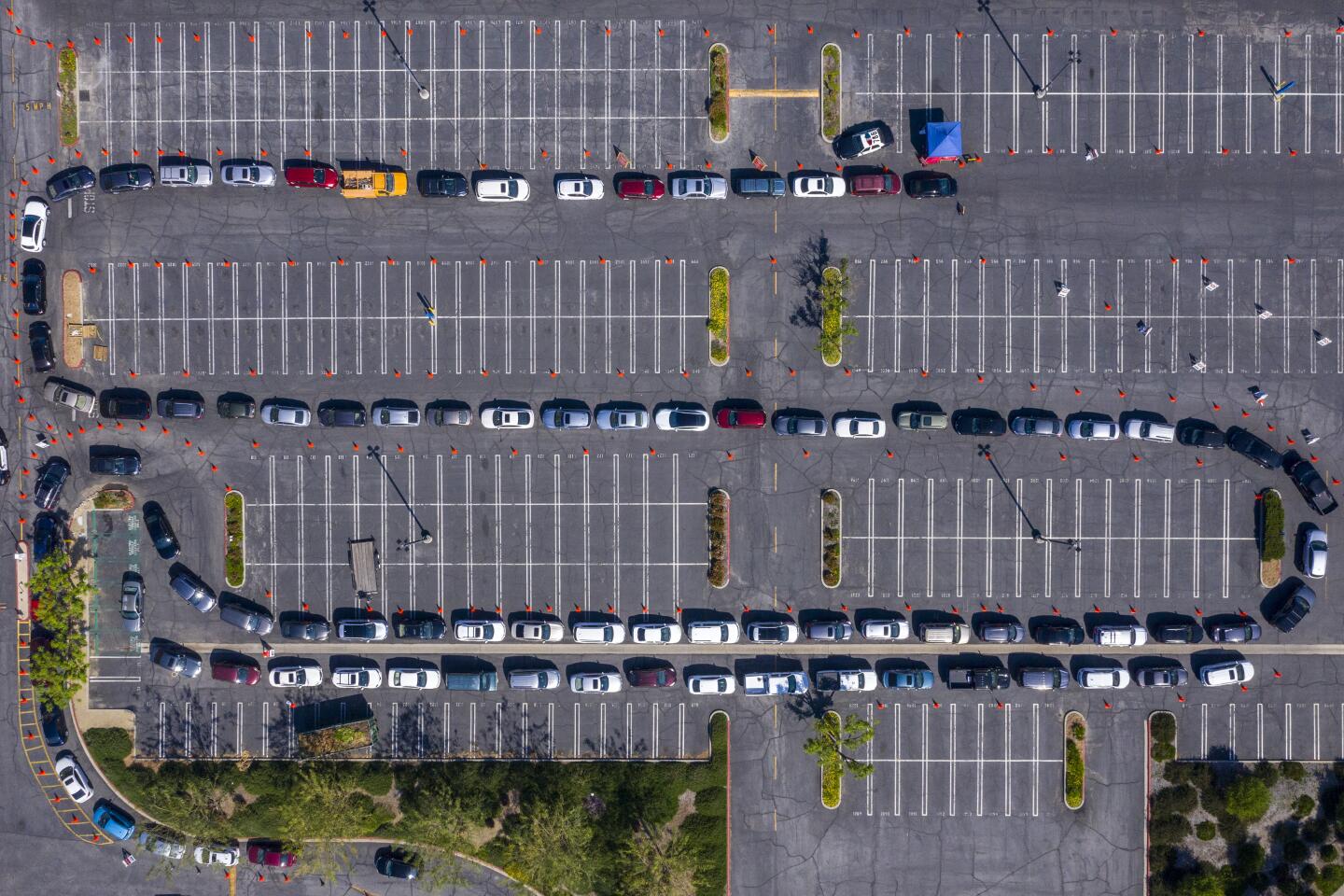

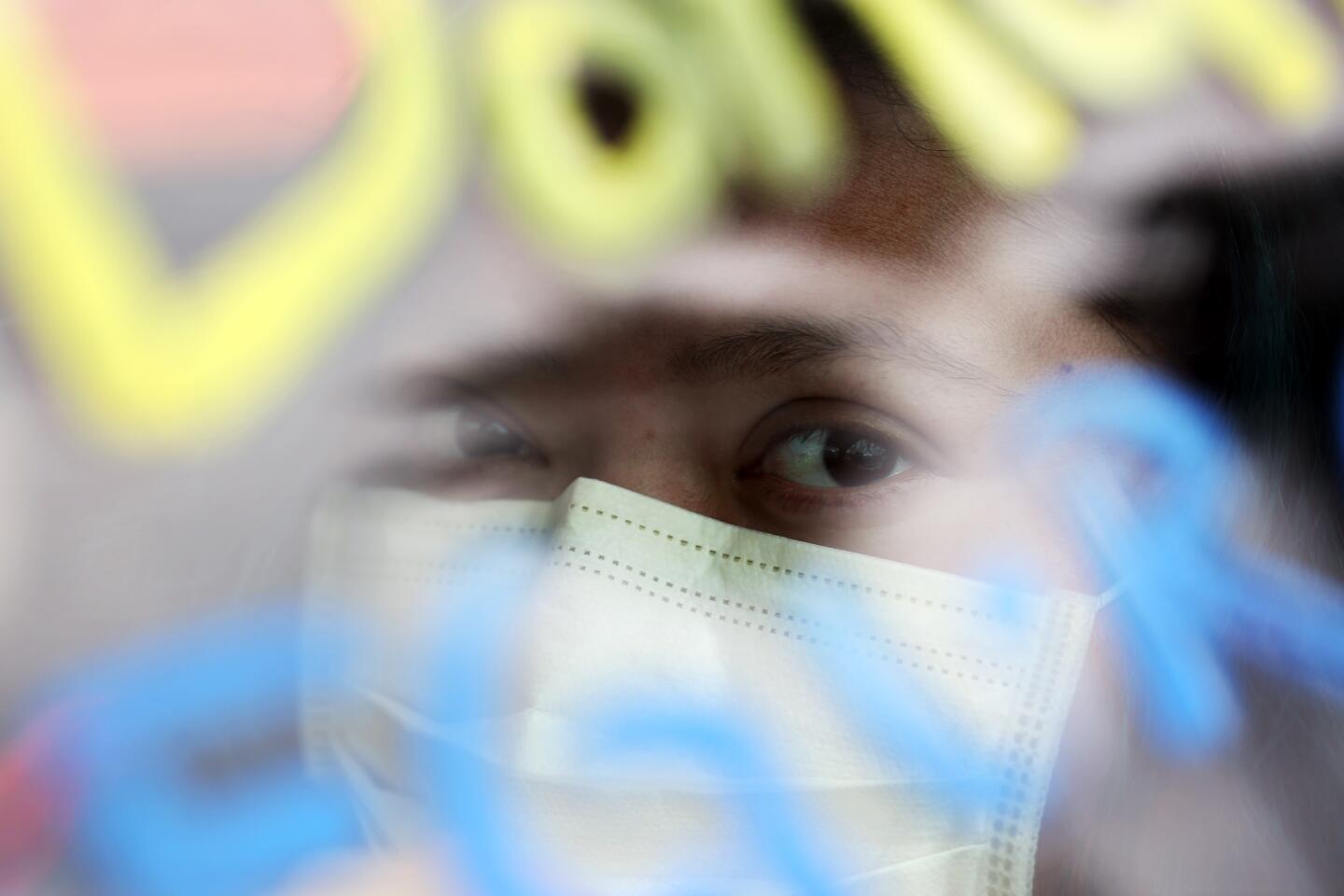

These are some of the unusual new scenes across the Southland during the coronavirus outbreak.

“If you have enough supplies in your home, this would be the week to skip shopping altogether,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Monday.

“Without everyone taking every possible precaution, our numbers can start skyrocketing,” she said. “It really is time for those people who maybe haven’t taken this seriously before ... this would be the week to stay home ... and it may be next week as well.”

While California has yet to see the worst of the pandemic, there were signs that some of the more dire predictions might not come to fruition.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has tried to prepare the state for the worst-case scenario, said California had enough ventilators to lend 500 to the Strategic National Stockpile to help New York and other COVID-19 hot spots facing shortages of the desperately needed medical devices.

“We want to extend not only thoughts and prayers, but we’re also extending a hand of support with ventilators,” Newsom said during a news briefing Monday in Sacramento.

In our effort to cover this pandemic as thoroughly as possible, we’d like to hear from the loved ones of people who have died from the coronavirus.

Newsom said lending the ventilators was possible because hospitals throughout California have procured thousands of them in the last few weeks, increasing their ventilator inventory from 7,587 to 11,036.

Also Monday, the influential Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, an independent population health research center at the University of Washington, predicted a significantly lower death count in California than its earlier models, based on new data from Spain and Italy.

On March 26, the center forecast 6,109 deaths in California during this outbreak, a number seen by many at the time as overly optimistic. On Monday, the institute reduced that projection to 1,783, with a range of uncertainty of 1,400 to 2,400 and the last death occurring on May 20.

The peak in patients is forecast to roll through hospitals on April 15, and the worst day for fatalities two days later, with 70 deaths.

The numbers changed largely because seven locations in Italy and Spain “appear to have reached the peak number of daily deaths,” the researchers wrote in their update. They no longer had to rely solely on data from Wuhan, China.

“The time from implementation of social distancing to the peak of the epidemic in the Italy and Spain location is shorter than what was observed in Wuhan,” they wrote. “As a result, in several states in the US, today’s updates show an earlier predicted date of peak daily deaths, even though at the national level the change is not very pronounced.”

New data also changed how the team weighed the effects of different social distancing factors — closed schools, stay-at-home orders, shutting down nonessential businesses — in its calculations.

The researchers’ model projects that the last death from the virus in the United States will occur on June 22 and that the nation’s total death toll will be 81,766, within a range of uncertainty of 49,431 to 136,401.

The states expected to be hit hardest: New York, 15,618 deaths; New Jersey, 9,690; Massachusetts, 8,254; and Florida, 6,770.

Epidemiologists have questioned the reliability of any prediction model, given the number of uncertainties plugged into the algorithms — erratic human behavior, spotty testing, possible under-reporting of deaths.

“When you multiply uncertainty with uncertainty, you get larger uncertainty,” said Dr. Loren Miller, a physician and infectious diseases researcher at the Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. “And that’s where models are limited. They can make guesses about what will happen, but they can be way off in either direction. Too optimistic or too pessimistic.”

Other models have projected far bleaker statistics. And critics of the University of Washington model have expressed fears that the Trump administration relies on it too heavily because it paints a brighter picture than others.

And all this could be just the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Others could follow in weeks, months or years.

California state officials expect that the peak of this outbreak will not be reached until mid-May and high infection rates could last into summer.

New documents reveal the scramble to get protective coronavirus gear to California hospitals. It’s a more complicated process than you would think.

The number of new cases in L.A. County has been rising steadily, with the number of daily new cases increasing from about 300 a week ago to between 422 and 720 in the last several days.

While the rate of growth slows near the peak, the sheer numbers get bigger every day. Doubling 10 cases in a single day is a high rate of growth. Doubling 6,000 cases in five days is a much slower rate of growth — with a much bigger impact.

Cases in Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego counties are now taking about four to five days to double, while Alameda, Contra Costa, San Mateo and Solano are taking six to seven.

The pace is slowing down even more in San Francisco, where the doubling time is every 10 days, and in the original epicenter of California’s outbreak, Santa Clara County, where the doubling time is now every 11 days. In mid-March, this was happening every four days.

Los Angeles County saw its fastest rate of coronavirus cases in late March, when it was taking just about every two days for coronavirus cases to double, the Times analysis found.

The Inland Empire is seeing a sharp rise in infections, with San Bernardino County reporting 157 new cases Monday, for a total of 530, a 42% jump.

Part of the reason for the faster pace of coronavirus cases in Southern California could stem from the Bay Area acting earlier to implement a stay-at-home order, said Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist and infectious diseases expert at UC San Francisco.

It’s our visual prompt to stay away, but stay-at-home orders have given new purpose to caution tape.

The Bay Area shocked the nation on March 16 when it was the first region in the nation to announce a shelter-in-place policy ordering residents to stay at home as much as possible.

The measures extended to Southern California on March 19, when Gov. Newsom announced a statewide stay-at-home order on the same night Mayor Eric Garcetti issued his own for the city of Los Angeles.

Case counts can be problematic in tracking the course of this coronavirus outbreak, given the limited availability of testing.

But they can still be helpful because they also translate to how many people are being seen in the hospitals to be treated for the COVID-19 disease, “so they’re reasonably accurate, and I don’t think there’s any big differential between Northern and Southern California in terms of ease of obtaining tests,” Rutherford said.

Times staff writers Ryan Murphy, Soumya Karlamangla and Phil Willon contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.