SARS killed hundreds and then disappeared. Could this coronavirus die out?

- Share via

The mysterious virus first emerged in the winter in eastern China, a never-before-seen pathogen that would rattle the world’s sense of safety and ignite a global panic.

In the months that followed, hundreds of people began seeking medical treatment because they were coughing, struggling to breathe and, in some cases, approaching death.

Scientists racing to quell the outbreak determined the source was a novel strain of coronavirus. The World Health Organization called for immediate action to prevent the global health threat from sweeping across multiple continents and killing thousands.

It was early 2003, the beginning of the battle against severe acute respiratory syndrome, more commonly known as SARS. The SARS outbreak was the first deadly epidemic caused by a coronavirus.

“It was a tremendous concern,” said Alan Rowan, a public health professor at Florida State University involved in Florida’s response to the SARS outbreak. “It was a novel virus, and it was frightening.”

Much like the strain of coronavirus currently spreading across the world, the SARS virus prompted people to hoard face masks, cancel trips to Asia and institute massive quarantines amid fears that the disease would become entrenched.

But eight months after SARS began circulating, it was contained. The virus died out.

The stamping out of SARS has been lauded as one of the biggest recent public health victories, achieved with a strong and swift response and a dose of good luck.

But as cases of the new coronavirus swell, it appears less likely that history is going to repeat itself. The virus’ path suggests containment will be much more difficult than with SARS and the harm much greater, experts say.

On Feb. 9, the death toll from COVID-19 surpassed that of SARS. In the days since, it has climbed even higher.

::

After originating in China’s southeastern Guangdong province in late 2002, SARS had spread by early spring to approximately 1,500 people.

Officials from the World Health Organization said SARS could become the most serious health threat to emerge in more than 20 years, with the exception of AIDS.

SARS was a pneumonia-like illness that killed about 1 in every 10 people struck, far higher than the estimated 1-in-50 mortality rate for COVID-19 infections.

“There was enormous panic,” said Lawrence Gostin, director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center on National and Global Health Law.

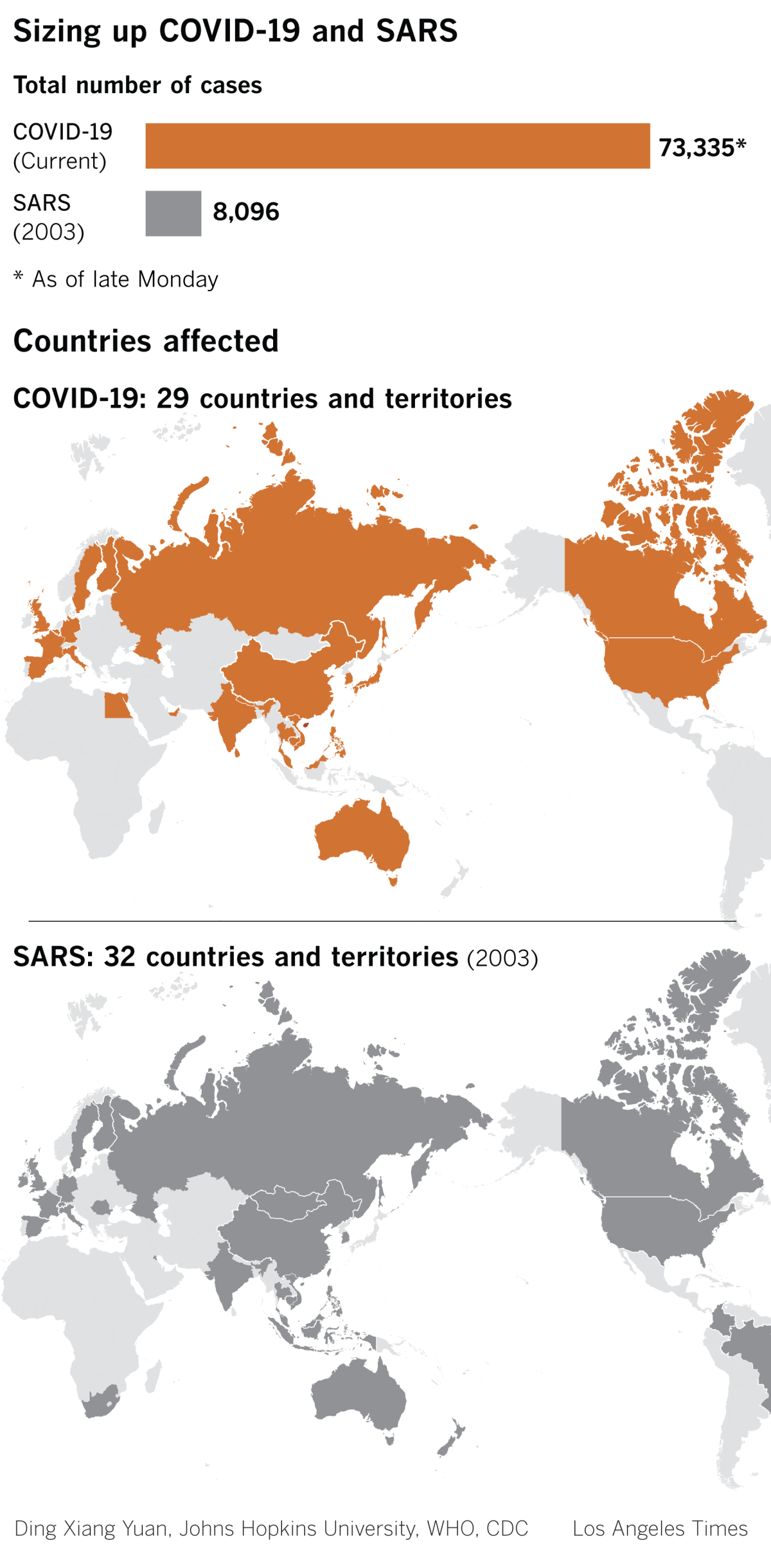

The SARS outbreak, which reached 29 countries, was ultimately contained using traditional public health measures, such as testing, isolating patients and screening people at airports and other places where they might spread the virus, Gostin said. The strategy is simple: If sick people can be stopped from infecting healthy people, the disease will eventually die off.

But limiting the current outbreak with these tried-and-true public health strategies has proved harder now because of the sheer number of cases, Gostin said.

By the end of the SARS epidemic, 8,000 people had been infected. Already, more than 73,000 people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, and some experts think undetected milder cases push the true tally even higher.

“It’s affecting hundreds of thousands of people, and potentially a lot more going forward. It’s really hard to contain once you’ve got that kind of saturation,” Gostin said. “This is a much bigger challenge than SARS.”

During SARS, remembered as the first pandemic of the 21st century, public health officials watched in horror as an interconnected, global society facilitated the spread of disease like never before. A Canadian couple who visited Hong Kong started a SARS outbreak in Toronto that killed 24 people.

Those risks are even greater now. Chinese people travel domestically and internationally at a much higher rate now than in 2003, which makes containment “that much more difficult,” Gostin said.

The World Health Organization has declared COVID-19 an international health emergency and announced Friday that the virus reached a fifth continent, Africa, after a case was detected in Egypt. Any dips in weekly case numbers should not be interpreted as signs of abatement, officials say.

“This outbreak could still go in any direction,” Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said during a news conference last week.

Officials know how fickle these viruses can be. The SARS response benefited from “good fortune as well as good science,” Dr. David Heymann, who led the World Health Organization’s infectious disease unit during the SARS pandemic, wrote in a 2004 paper evaluating the international response to the disease.

Officials were lucky that SARS never popped up in developing countries with less sophisticated healthcare systems that would have struggled to contain the illness, he wrote. The virus was also easier to stop because it turned out to have relatively low transmissibility, he wrote.

“Its rapid containment is one of the biggest success stories in public health in recent years,” Heymann wrote. “How narrow was the escape from an international health disaster? What tipped the scales?”

Scientists will probably soon find out. SARS and COVID-19 are like cousins, sharing 70% of their genetic material. Both are coronaviruses, a family of viruses that before 2003 had been known to cause only the common cold in humans.

While the SARS virus replicated deep in people’s lungs, probably contributing to the higher mortality rate, that also made it less likely to spread than the COVID-19 virus, said Dr. Stanley Perlman, a microbiologist at the University of Iowa who studies coronaviruses.

The new coronavirus grows in people’s noses and airways, so it can be more easily spread through coughing and sneezing, like the flu, he said. Though people with SARS probably weren’t contagious until they were very ill, that isn’t the case for COVID-19, so it will be harder to catch people before they infect others, he said.

“As soon as you start having very, very minor symptoms, that sore throat, that itchiness, that sneezing, then you’re contagious,” Perlman said. “I don’t think it’s going to be like SARS and just go away.”

Even if COVID-19 doesn’t die out, it could wane so much that cases become extremely rare, or emerge only in the winter. Viruses tend to have seasonality, appearing for only a few months a year, so some hope warmer weather will make the virus recede.

With this outbreak, international officials were notified much sooner and the virus was sequenced much faster than with SARS. Yet COVID-19 remains trickier to get ahead of because of the virus’ traits, said Brittany Kmush, a public health researcher at Syracuse University’s Falk College.

Viruses spread most when they are very contagious and not that deadly, she said. If a virus is very lethal, patients often die before they can transmit the illness to many other people.

COVID-19’s low mortality rate compared with SARS, though a relief to doctors, may actually hinder prevention efforts, she said.

“I think if SARS had similar characteristics to this coronavirus, it would still be circulating,” Kmush said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.