How Jackie Lacey’s and George Gascón’s time in office shapes the L.A. County D.A.’s race

- Share via

Jackie Lacey and George Gascón spent more than three decades each working for and eventually running some of the nation’s largest law enforcement agencies.

Yet, their visions to lead the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office couldn’t be more different.

Lacey, the two-term incumbent who oversees the office she’s worked in since the late 1980s, has long tried to improve treatment for mentally ill defendants and tried to position herself as a reformer on other issues. But her reputation is that of a punishment-first prosecutor. While she’s beloved by the law enforcement community, Lacey’s tenure has been marked by a perceived hesitance to charge powerful figures and police officers who use deadly force, earning her the scorn of local activist groups.

Gascón, the former San Francisco district attorney and assistant chief of the L.A. Police Department, has emerged as one of the leaders of a movement to elect progressive prosecutors, aiming to lower crime while reducing the number of people affected by the criminal justice system. His ideas have been hailed by some, but a surge of property crimes in San Francisco has led detractors to claim his election here would endanger public safety.

The Times reviewed crime statistics, filing rates and other data spanning Lacey and Gascón’s terms in Los Angeles and San Francisco. The review highlights stark differences between the two but also upends some narratives painted by each candidate’s most ardent supporters.

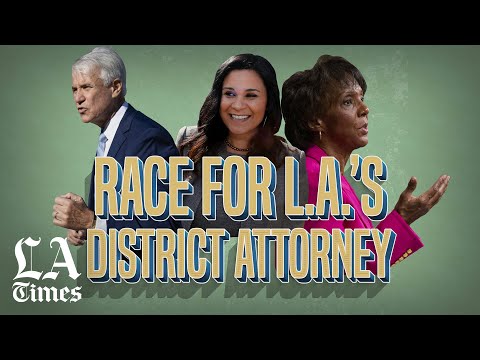

Voters will choose between Lacey, Gascón and former public defender Rachel Rossi when they go to the polls March 3. Unless one of the three candidates receives more than 50% of the vote, the top-two finishers will go head-to-head in November. With rock solid support from law enforcement and local elected officials, and Rossi’s potential to draw left-leaning voters away from Gascón, political observers think Lacey is the only candidate with a chance of claiming outright victory in March.

Surge in crime

During Gascón’s tenure in San Francisco from 2011 to 2019, property crime surged by 49%, driven by an unprecedented increase in vehicle break-ins, records show. Violent crime also increased 15% in the same time frame.

Under Lacey, however, violent crime rose at a much higher rate in Los Angeles. Countywide, violent crime jumped 31% from 2011 to 2018, and 44% in the city of Los Angeles over the last eight years, according to data reviewed by The Times. While some of the citywide increase can be attributed to the LAPD’s failure to properly classify aggravated assaults, records show violent crime continued to trend upward even after the data problem was fixed.

Lacey dismissed the countywide data during a recent debate, blaming the increase on a change in the way the California Department of Justice tracks sexual assault cases. In a recent interview with The Times, she acknowledged she “owned” the crime hike in Los Angeles but also suggested responsibility for such issues lay with police officers, not prosecutors.

“I think policing plays more of a role in those crime figures. But your D.A. sets your tone in the city ... your D.A. should be outspoken about protecting victims and putting public safety first,” she said, implying Gascón had failed to do the same.

Homicides have fallen citywide by 15% under Lacey, according to LAPD data. Killings dipped slightly during Gascón’s term in San Francisco as well, with the city seeing just 41 homicides in 2019, its lowest total in a half-century.

Some have blamed Gascón’s reticence to prosecute low-level crimes for the surge in car break-ins on his watch. During his two terms, San Francisco prosecutors filed criminal charges in only 40% of misdemeanor cases presented by city police.

By comparison, Lacey’s office filed on 86% of all misdemeanors presented to them. Records show Los Angeles prosecutors were also more likely to file charges in felony cases on Lacey’s watch, prosecuting 59% of all cases presented by law enforcement during her eight years in office. In San Francisco, Gascón’s office filed about half of all felony cases.

Gascón said the low misdemeanor filing rate should be considered an accomplishment. When he took office, he said San Francisco prosecutors were wasting time and resources prosecuting nonviolent offenders who were experiencing some combination of mental illness, addiction and homelessness. Gascón said he didn’t see the value in prosecuting minor offenses that would serve only to increase a defendant’s propensity toward crime.

“Each segment of the homelessness problem is sometimes driven by the criminal justice system,” he said. “By putting people even for short terms, in jail, when they are poor, they lose their jobs, the safety net is not there and then they lose their homes.”

Gascón and Rossi have both called for ending prosecutions of homeless defendants for crimes that are solely the result of their situation — including public urination or violation of open container laws.

The true progressive?

Of the three candidates, there is little question Gascón has the most outsize reputation as a criminal justice reformer. In the span of eight years, he co-authored Proposition 47, expunged thousands of marijuana convictions after California voters legalized cannabis, put San Francisco on a path to reduce the use of cash bail and instituted a program that allowed prosecutors to make charging decisions without knowing the race of a suspect.

Gascón said that track record shows he can strike the balance between enforcement and restorative justice that is necessary for a 21st century prosecutor.

“I think it’s a role that requires a lot of nuance, that you have to be really thoughtful about the awesome power that you have because … I don’t want to sound corny here ... but it should be used because it’s for the greater good, and not just simply because you’re so keenly focused on a very narrow part of your work, which is that of punishing,” he said.

Lacey has often championed the rights of mentally ill defendants, launching an alternative sentencing program aimed at helping individuals find housing and treatment after completion of a 90-day probation period and another effort that allows defendants in some nonviolent misdemeanor cases to have their records expunged of a criminal charge, a boon for homeless defendants for whom a conviction can be a barrier to housing.

These defendants “probably shouldn’t be in the criminal justice system,” Lacey said. “Is it a first-time offense ... is it drinking in a public park? To me, that doesn’t make sense for us to spend time putting them in the system.”

In the last year, 490 defendants “entered into” a signature mental health diversion program, according to a spokesman for the district attorney’s office. Nearly 300 were granted diversion and 80 of those defendants have successfully completed the program. Only 47 were outright rejected, records show.

Some critics contend that the bar for entry into Lacey’s programs is too high. A report published by the Rand Corp. last month, however, estimated there are 3,368 people currently held in L.A. county jails who are struggling with mental illness and would be appropriate candidates for a diversionary or treatment program, rather than incarceration.

While she doesn’t share the lengthy resume of Lacey or Gascón, Rossi might prove attractive for voters looking for an outsider to take command of the district attorney’s office. The career public defender played a role in drafting the First Step Act, a bipartisan federal prison reform bill signed into law by President Trump in 2018 that reduced some mandatory minimum sentences and opened pathways to early release for lower-risk inmates.

Rossi has argued that her lack of a law enforcement background is an asset to her candidacy. While her opponents talk about the need to protect crime victims, Rossi said her experience allows her to better identify those who need help rather than jail time.

“When it comes to mental health diversion we know for a fact that there are people who can succeed in diversion who are currently incarcerated ... what we need to do is shift away from the old tough on crime equals reduced crime adage, and start looking at data,” she said.

Use-of-force oversight

Protesters have chastised Lacey and Gascón for declining to prosecute officers in a number of controversial fatal shootings, including the death of Mario Woods in San Francisco and Brendon Glenn, an unarmed homeless man who was shot near Venice Beach. In the latter case, Lacey went so far as to ignore the recommendation of then-Police Chief Charlie Beck to prosecute the officer. She did charge a sheriff’s deputy with manslaughter for an on-duty shooting in 2018.

Rossi has called on the attorney general’s office to grant district attorneys the power to appoint independent investigators to review use-of-force cases, while Gascón has previously lobbied for laws that would change the rules governing when officers can use force. Lacey, meanwhile, has often sided with law enforcement, arguing that initial public perceptions are often inaccurate.

“When those cases come in and we really dig deep and look at them they’re a lot more challenging than they first appear,” she said

Records show that San Francisco prosecutors filed nearly three dozen misconduct cases against law enforcement officers while Gascón was in office. Six officers were charged with assault under color of authority and other officers faced charges for on-duty crimes including perjury, misuse of a government database and filing a false report.

In Los Angeles, the Justice Systems Integrity Division has filed roughly 90 cases against police officers since 2013, records show. Lacey’s office has secured convictions against a number of Los Angeles police officers and sheriff’s deputies for on-duty sexual assault, and also pursued a number of probation officers for excessive use of pepper spray on juvenile detainees. Several of those probation officers were recently acquitted.

Decisions called into question

Questions about Lacey’s handling of police shootings highlight a broader criticism of her time in office — the perception that she often lets politics get in the way of charging decisions.

She waited two years before charging Democratic donor Ed Buck in a spate of alleged drug-fueled sexual assaults, ultimately deferring to federal prosecutors to pursue Buck on the most serious charges. Lacey has also drawn fierce criticism for offering a plea deal to a city firefighter who nearly choked a man to death in a 2017 brawl. The firefighter was represented by a defense attorney who served as Lacey’s 2012 campaign manager.

Those criticisms came to a head last month when Lacey filed sexual assault charges against former film mogul Harvey Weinstein on Jan. 3, just one day before jury selection began in his Manhattan trial. Some observers and law enforcement experts wondered whether Lacey had timed the filing for maximum political gain. Of the two women’s allegations that led to charges against Weinstein, officials said the first one was presented to Los Angeles prosecutors in February 2018, nearly two years before Lacey filed.

Lacey said the Weinstein case was filed as soon as it was ready, and noted her office needed time to corroborate each accuser’s story. One of the two women lives abroad and her case was referred to Lacey’s staff from the Manhattan district attorney’s office, further complicating the issue, she said. Asked to respond to broader criticism of her office’s filing decisions, Lacey said she simply follows the law.

“We file. We do our job. We prosecute whoever without holding a metaphoric scalp out there and saying look at the latest police officer we’re prosecuting,” she said.

Gascón’s campaign was quick to attack Lacey over her decision-making in the Weinstein case, a move which shocked some women’s rights activists who allege he has his own checkered past when it comes to sexual assault prosecutions.

“Under Gascón, the San Francisco district attorney’s office had an unbelievably high bar for what they believed in order to charge a rape case,” said Jane Manning, a former sex crimes prosecutor who now serves as director of the Women’s Equal Justice Project. “I was in a room with George Gascón and heard him tell a rape survivor ‘I believe you. I believe that you were sexually assaulted,’ and then tell her that he would not charge her case.”

The controversy led the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to call a hearing in 2018 at which Gascón’s office, local police and hospital officials were all criticized heavily for their handling of assault cases, according to a report in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Gascón said his office prosecuted sex assaults at a rate that is twice the national average for a district attorney’s office, though Lacey and Manning have disputed the accuracy of that number.

Given the ideological chasm between Lacey and her challengers — as well as growing pushback against other lauded national criminal justice reform efforts such as New York’s recently instituted bail law — some experts believe the primary could forecast just how serious voters are about rethinking the role of a prosecutor.

“All eyes will be on L.A. to see whether there’s an appetite to push further or whether there’s gonna be a cooling off period. I think that’s where we’re at this point. There’s going to be major interest to see how far the voters are willing to go on this,” said Eugene O’Donnell, a former New York City prosecutor and police officer. “Without a doubt criminal justice reform will continue to happen, but there is some evidence that people are getting cold feet about the extent of it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.